Did Joan Mitchell Have the Finest Mind in Modern American Art?

When artist Joan Mitchell was born in 1925, her father wanted a boy. He let her know that her entire life, leading her to seek psychiatric help. As much as that experience shaped her mind, Joan’s mind already set her apart, and set her on the course to become an artist. As revealed in Patricia Albers’ Joan Mitchell: Lady Painter, the first full-length biography of the artist, Mitchell had both synesthesia and an eidetic memory. In other words, Mitchell saw much of the world—letters, sounds, people, and even emotions—as colors, while at the same time remembering every detail of the past as vividly as the present. That unique combination and Mitchell’s drive to become an artist helped her rise within the male-dominated art world of the 1950s. Albers’ sensitive and insightful biography provides a whole new vision of Mitchell and her art and raises fascinating questions about what it meant to be an artist and a woman in 20th century America.

Albers’ revelation of Mitchell’s synesthesia and eidetic memory steals the show initially. Of contemporary artists, David Hockney is also believed to be synesthetic. Artists such as Van Gogh may also have been synesthetic. Mitchell hid her condition during her lifetime, vaguely alluding in interviews to the colors she saw when listening to music, meeting people, or experiencing emotions. But, Albers cautions, “[t]o reduce [Mitchell] to a case is to disregard her painterly intelligence, her professionalism, her years of training and work.” Mitchell’s unique perceptions may have served her art, but it was her devotion to her craft and fierce intelligence and passion that made her who she was.

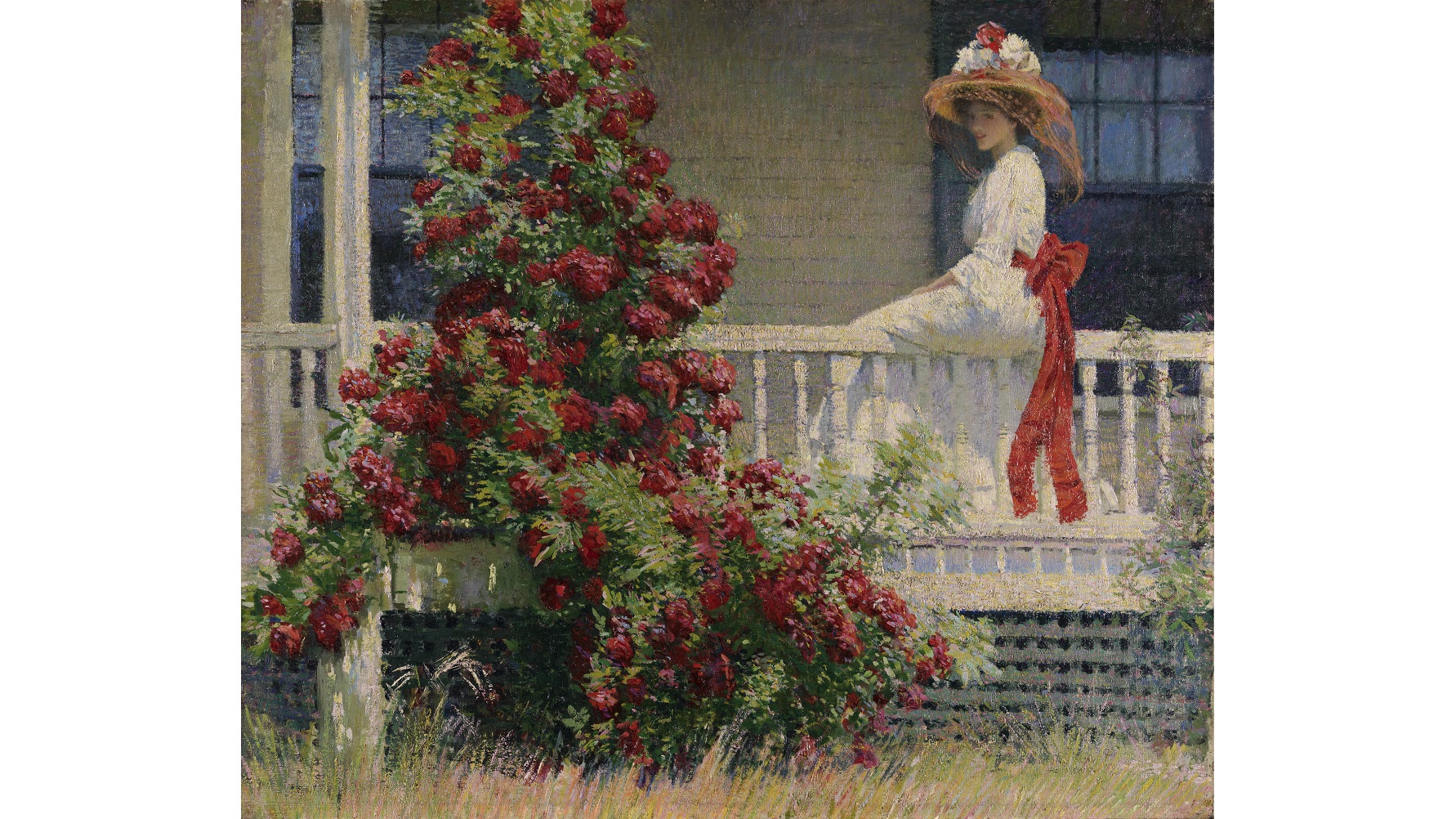

Mitchell fed her fascinating head furiously. Daughter of the poet Marion Strobel, Joan read voraciously, finding herself drawn, among others, to Wordsworth and Proust—two writers who probed memory in ways that captivated her. Whenever she painted, Mitchell played music—everything from Mozart to the Blues to Charlie Parker to Billie Holiday. The music inspired colors in her imagination that fueled the paintings flowing from her hands. Painting became an ecstatic, religious epiphany. “Mitchell might have had Blue Territory [detail shown above] in mind when she bemoaned to a colleague that art had ‘lost some of its spirituality,” Albers writes, “Not only does Blue Territory conjure a book of hours… but also shines as Mitchell’s Starry Night.” As mind-blowing as thinking about Mitchell’s mind is, Albers manages to keep pace with the dizzying possibilities and helps us follow, too.

Joan Mitchell: Lady Painter adds to the growing literature of how women American artists struggled to find their place—not as a homogenous group but as vibrant individuals. Along with Gail Levin’s Lee Krasner: A Biography and Becoming Judy Chicagoand Albers’ own Shadows, Fire, Snow: The Life of Tina Modotti, biographers continue to build a strong case for reevaluating feminism as a whole by reevaluating individual women. “So women had to be really tough, Joan believed,” Albers writes of Mitchell’s brand of 1950s feminism. “[S]he was too proud to protest or complain. Those who did were crybabies and losers.” In the 1970s, feminists looked to Mitchell, only to find her “cranky and contentious,” Albers explains, and suspecting that those women who fought for their rights were unable to win them by talent alone.

Talent got Mitchell into the door of the men’s club of Abstract Expressionism, but it was her spirit that allowed her to thrive there where others failed. When Joan entered the “gladiatorial” atmosphere of the infamous Cedar Tavern—hangout of Pollock, de Kooning, and the rest—she found herself groped as a sex object, like all the other women, but had the guts to grope back. Soon, the men got “a kick out of that blend of moxie and brains that had her swearing like a sailor in one breath,” Albers recounts, “and quoting [T.S.] Eliot in the next.” To paint “like a man,” Mitchell smoked, drank, and had sex like a man, except she faced the horrors of rape and abortions they couldn’t. Mitchell paid a price to enter that boys’ club, which Albers unflinchingly explains.

Joan Mitchell adopted the sobriquet “Lady Painter” with all the acidity and absurdity she could. Knowing that she could paint as well as any man, Mitchell also knew that no man would admit it. Walking around her 1988 retrospective at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Mitchell gazed upon her works and said with a smirk, “Not bad for a lady painter.” As much as you want to ascribe sadness to such injustice, you can’t help but come away from Joan Mitchell: Lady Painter smiling at Mitchell’s ability to convey her inner life into her art and find pure joy in the colors of the world, even if that world denied her full acceptance. Patricia Albers never lets us forget the wonder that was Joan Mitchell—in every sense of the word.

[Image:Joan Mitchell. Blue Territory, 1972 (detail).]