Are We Still Living in the Age of Pop Art?

After World War II, America emerged as the single, unquestioned superpower in one respect—it’s popular culture. While the Cold War simmered, people around the globe consumed American movies, music, and television. When Pop Art transformed that popular culture into an art movement, even that evolution was exported. The exhibition International Pop traces the convoluted lines of influence, positive and negative, of Pop Art and maps out a visual history of the second half of the 20th century, particularly the tumultuous 1960s, when the world “turned on” and turned upside down. Looking back through this exhibition, one can easily ask if we’re still living in the Age of Pop today.

The thumbnail history of Pop Art usually goes like this: Andy Warhol one day started painting soup cans and Brillo boxes, decided everyone should be famous for 15 minutes, and became the bewigged genius of 1960s art. International Pop fleshes out the more complex, more interesting truth. Warhol didn’t invent Pop Art. British artist Richard Hamilton (whose Hers is a Lush Situation is shown above), among others, was creating in that style before Warhol. “Denying a narrative focused on defining points of origin,” Darsie Alexander writes in the catalog, International Pop “instead emphasiz[es] the flows and exchanges of Pop… consistent with a phenomenon that was constantly evolving.” The 1960s were anything but simple or straightforward, so why should its art be?

International Pop challenges Pop Art preconceptions down to the very name “Pop Art.” Common Object Art, Factualist Art, Neo-Dada, New Realism—those are just some of the forgotten runners-up to Pop Art. “We suggest that Pop is either the best wrong term for the work in this show or that the whole thing needs to be rethought, revalued, and re-energized—precisely the enterprise with which we are engaged,” Alexander and Bartholomew Ryan argue in the catalog. In a visually and intellectually stirring visual chronology of International Pop (just part of the catalog’s fascinating design concept typical of the Walker Art Center’s design team), Godfre Leung suggests that “the term Pop… contains a double meaning that simultaneously reflects its reach—popular—and the instantaneousness of that reach—onomatopoetically, Pop!” Rather than art historical navel gazing, International Pop challenges us to look again (as Joe Tilson commands in LOOK!, shown above) at Pop Art and see it as something more socially connected back to the world then and, possibly, now.

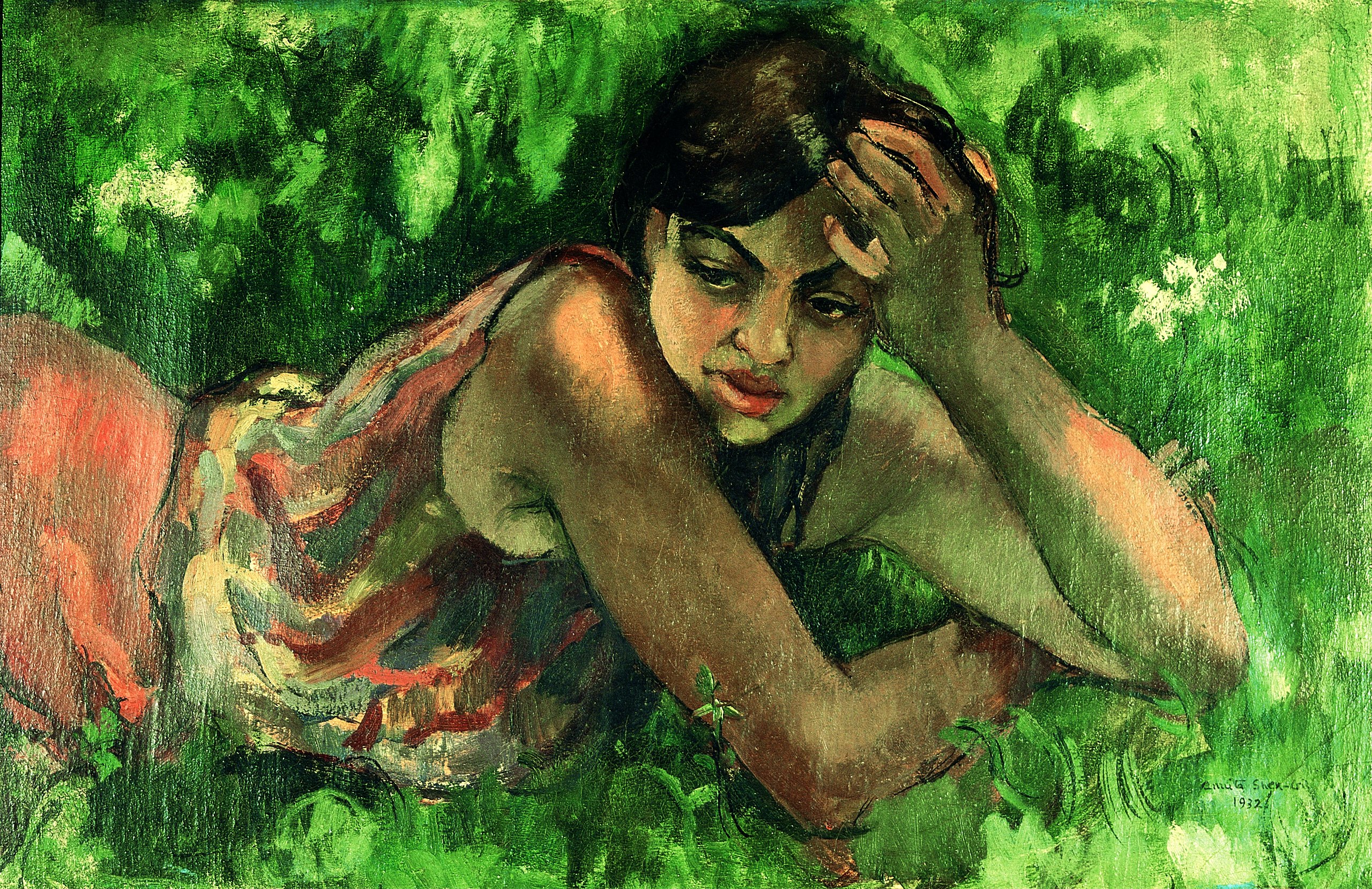

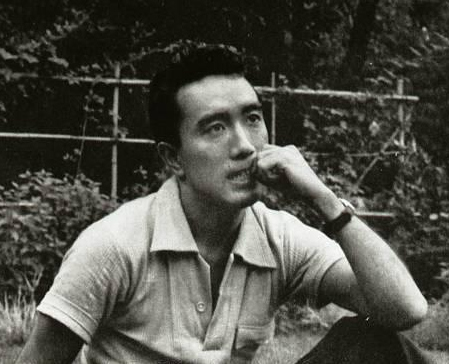

The exhibition focuses on five hotbeds of Pop Art: Britain, Brazil, Germany, Argentina, and Japan, specifically Tokyo. “Tokyo Pop” arises from a combination of the post-World War II American occupation’s “enlightenment campaign” inundating the Japanese with Americana and the already existing Japanese tradition of print and graphic arts. Thus, as Hiroko Ikegami puts it, “Tokyo Pop” “employed self-conscious means in order to question the very object of their embrace—with an antagonistic yet playful spirit.” This love-hate relationship appears in works such as Ushio Shinohara’s Oiran (shown above), in which the artist reimagines a traditional ukiyo-e woodblock in garish Pop colors but creates a blank void where the face should appear. “Oiran” means prostitute in Japanese, raising questions as to whether Japan had prostituted itself in forgoing its own traditions and adopting foreign ones, literally a “loss of face.” Two animated films shown in the galleries—Keiichi Tanaami’s Commercial War and Good-By Elvis and USA—raise the same question even more provocatively.

The United States didn’t occupy Brazil after World War II, but they might as well have. The 1964 Brazilian coup d’état, in which the U.S. backed the military overthrow of Brazil’s democratically elected government by the Brazilian military, instilled a wariness of all things American in Brazilian artists, especially Pop Art. They saw Pop Art not only as “a tool to promote consumerism and to advance art deliberately produced for the market,” Claudia Calirman argues, but also “apolitical and an instrument of American imperialism.” Rejecting the content of Pop Art (including its celebrity idolatry), Brazilian artists embraced Pop Art’s spirit of celebrating the individual—not movie stars, but rather the individual facing powers beyond their control. While Warhol made Sixteen Jackies (his homage to Jacqueline Kennedy that appears in the exhibition), Hélio Oiticica made Be an Outlaw, Be a Hero (Seja Marginal, seja herói)(shown above), his homage to the heroic, faceless individual fighting injustice.

International Pop fights against every preconceived idea you may have ever had about Pop Art as disengaged, apolitical, or sexist. And even when such ideas are partially true, they present Pop Art’s self-critique. Just as the Japanese and Brazilians pushed back against the American politics embedded in Pop, artists such as Evelyne Axell fought against Pop sexism while celebrating female Pop sexual freedom. Too hot for Facebook even in 2016 (which tried to censor it from social media promotions), Axell’s 1964 Ice Cream (shown above) shows a woman provocatively licking an ice cream cone in vibrant Pop colors and symbolically sticking her tongue out at those male Pop Artists who served up little more than reprocessed cheesecake. Similarly, Paul Thek’s Meat Piece with Warhol Brillo Box upends the conventional Warhol tropes of Pop Art to reveal the meatier, messier underside this exhibition explores.

One of the many things that makes International Pop so intriguing and enjoyable from beginning to end is the soundtrack, which you can access as a Spotify playlist. Featuring the Beatles, Sonny and Cher, Bob Dylan, Nina Simone, and other ‘60s music stalwarts, the soundtrack leans heavily on the Velvet Underground (shown above), the group Andy Warhol all but christened as the Pop Art house band. Serious (and international) enough to include Antonio Carlos Jobim and Françoise Hardy, yet fun enough to feature the theme from Batman, TV’s first Pop Art program, the playlist does in sound what the exhibition does in visuals. The British Invasion didn’t happen only in one direction. Without American Blues, the Rolling Stones never start rolling. Likewise, the military, cultural, and artistic invasions of International Pop don’t cross in any one direction but as a series of double crosses (pun intended) in which exports and imports are consumed and then spat back out depending on the tastes and perspective of the consumers.

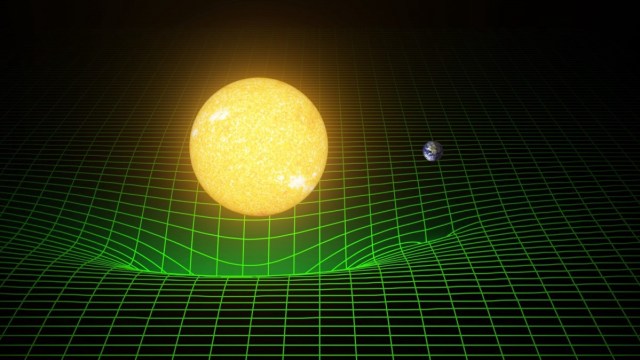

Taking in the diversity and depth of International Pop often feels like trying to swallow the vastness of Erró’s Foodscape, which depicts materialism and commercialism beyond all limits, yet also feels like a visual representation of the internet, something the artist couldn’t have imagined in 1964. If the 1960s took a closer, faster, and more pervasive look at popular culture than ever before to form what British artist Pauline Boty called a “nostalgia for now,” what would we call our relationship to popular culture now, when technology literally makes every song, video, etc., a click away whenever, wherever we feel nostalgic enough to want it? Afraid once of the military-industrial complex, should we now fear a military-industrial-entertainment-media complex in which pop culture stars run political campaigns indistinguishable from reality television? The curators of International Pop argue that Pop fizzled out in the early 1970s, when the “Nixon shock” ended the Breton Woods system that coupled the U.S. dollar to gold, thus changing the financial world Pop Art’s commercialism based itself on ever since. Looking back, Pop Art might have ended in name only, with even more interconnectedness and speed connecting—and threatening—the world today. Warhol’s dead, but the Age of Pop lives on.