Columbia Professor: The War on Drugs Is a War on Race

For centuries Europeans drank—and for some today, drink—a lot of ale. Numerous accounts of polluted water in the 13th to 18th centuries abound, which apparently forced the citizens of London and Germany to drink plenty of alcohol—one entry from St. Paul’s Cathedral allowed for one bola (gallon) per person every day. Others claim that such an amount was unsustainable on the environment, if not the liver.

Whether or not the English and Germans drank a gallon a day, it is certain that beer was an integral part of daily life, especially in monasteries. While it was common knowledge that a little alcohol elevates the spirits, it certainly was not considered a drug. At least a portion of the water sources really were contaminated. Even if widespread pollution is a myth, who wouldn’t want to believe it true if the solution meant breakfast with ale?

Our beliefs about the substances we ingest have always dictated public attitude toward them. “Drug” is a relative term. Ayahuasca has long been medicine for the soul—advocates call it “grandmother medicine,” with the grandfather being peyote. Marijuana’s history as a Schedule One substance is much shorter than its common usage in numerous cultures. Substances that alter consciousness are usually deemed sacraments, not sacrilegious. That changed roughly 50 years ago from a policy perspective.

That attitude changed for the same reason that the idea of building a wall on our Mexican border persists: racism. Carl Hart, who chairs the Department of Psychology at Columbia University, recently stated that the war on drugs is simply a war on race. This is not mere speculation. Last year an interview was published with a former aide to Richard Nixon in which he stated the war on drugs was specifically waged to put down any chance of minority revolt.

“Drugs” are simply chemical substances with a physiological effect. Sugar is a drug, as is tobacco and caffeine, all of which have detrimental effects when used in excess. A beer a day might not be a bad thing, but a six-pack (or gallon) daily slowly kills you. Since these are socially acceptable and legal, we tend to gloss over their categorization as drugs. We certainly don’t have moral directives against these substances, save for certain religious groups, such as Mormons opposing alcohol, tobacco, and caffeine—at least in the form of coffee and tea since no sanctions against soda and chocolate exist. As stated, it’s always relative.

The relativity of drugs within groups is one thing. When it affects policy, however, a moral argument is waged against citizens who might not share those morals, and that is a problem. While we are currently undoing five decades of marijuana prohibition Jeff Sessions has recently stated that marijuana is “only slightly less dangerous” than heroin—a provably false claim. Society is waking up from a daze; our attorney general is attempting to keep us in it.

Sessions, who also champions Nancy Reagan’s failed war on drugs—the same racially motivated drug search Nixon, in a lineage kicked off by Harry Anslinger, initiated—is partaking in the same form of verbal gymnastics his forebears used. In his imagination, marijuana is a gateway drug. Reagan went a step further when she personified drugs:

Drugs steal away so much. They take and take. Drugs take away the dream from every child’s heart and replace it with a nightmare.

Trade one boogeyman for another, in this case the “other” races in our nation. Hart argues that such language confuses the public. It’s not only the drug that is vilified, but the ethnicities most associated with using that drug—an approach that recently hit a roadblock with the opioid epidemic.

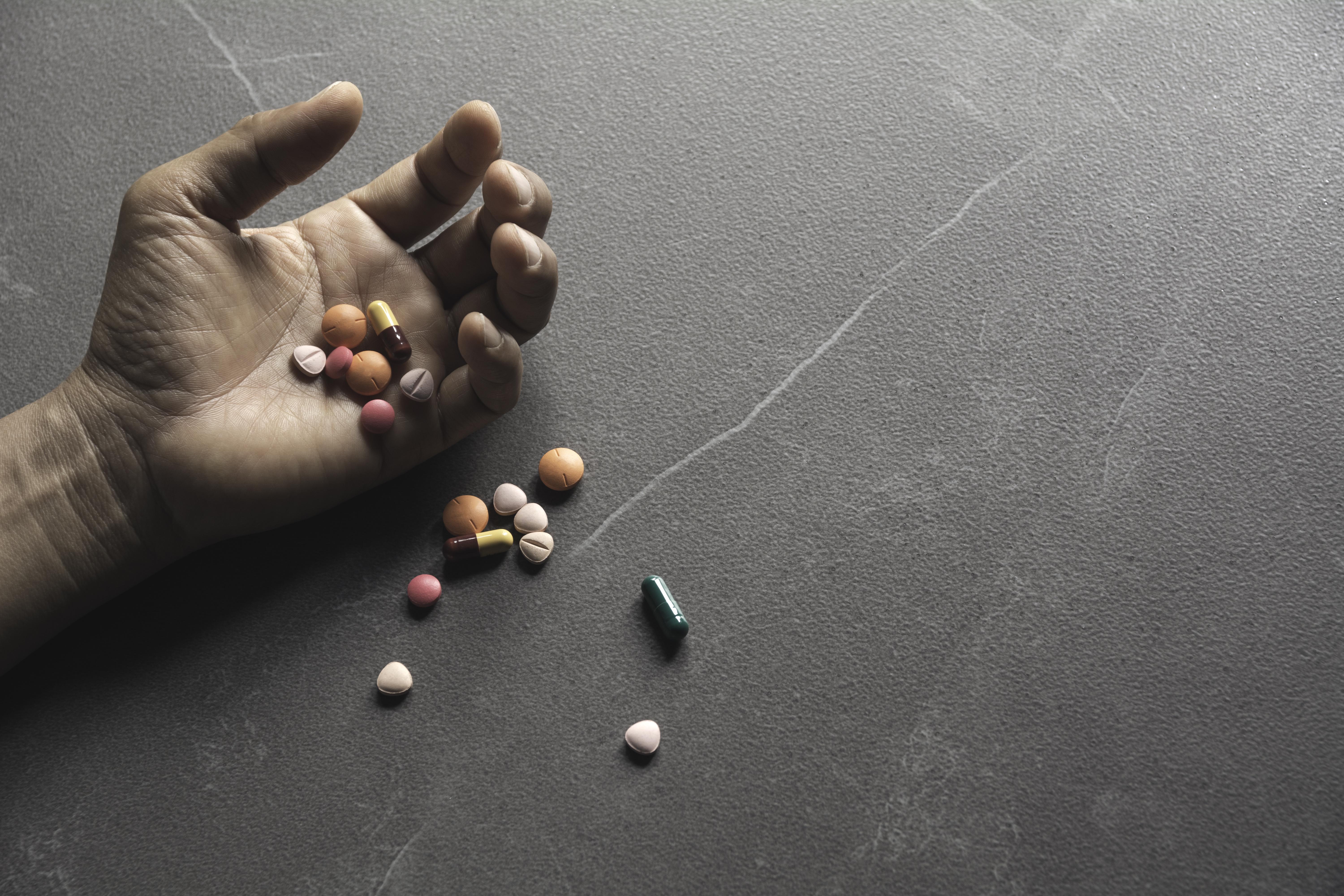

Oxycontin, a commonly prescribed opioid, and a flowering cannabis plant.

Strangely, we’ve never had a marijuana epidemic. Yet no substance has been used to incarcerate more Americans. Marijuana is not being and has never been treated as an issue of rehabilitation, as is occurring in communities plagued by opioids. Hart believes this strikes at the heart of the race issue. Discussing other nations with more sensible drug policies, he says:

They do this all around the world, because their first concern is keeping people safe, and not morality.

Why are morals not being used to combat opioids, especially considering numerous people use marijuana for the very same reason—pain relief? In 2015, 52,000 people died from overdoses; two-thirds of those were associated with opiates such as fentanyl and OxyContin. This has prompted Senator Claire McCaskill to ask pharmaceutical companies to release literature they use to influence doctors to prescribe their drugs.

As long as drugs like marijuana remain Schedule One and no national legislation addresses legality (as is happening in the states), such a question remains impossible to ask. But it does show the different approach politicians are taking to this particular drug problem. Sessions has never discussed opioids as a gateway drug; he has even called data showing legalized marijuana helps combat opioid addiction “stupid.”

As Saralyn Lyons reports in Johns Hopkins University’s HUB:

To keep drug policy in America from being hijacked by morality and exaggeration, Hart encouraged a reframing of the conversation: Drug users should “come out of the closet” to change the narrative that users are inherently abusers. “Drug users are me,” he said.

Personifying certain drugs as evil while calling opioid users “victims” strikes at the root of this linguistic (and psychological) posturing. Hart suggests a more compassionate approach, not one sponsored only by a “white face,” to deal with our actual drug problems—this includes crack cocaine in minority communities, another drug treated as a crime and not a tragedy. This means removing morality from the picture to investigate the real effects of each drug and how we’re addressing them. And that means being honest with data.

—

Derek’s next book, Whole Motion: Training Your Brain and Body For Optimal Health, will be published on 7/4/17 by Carrel/Skyhorse Publishing. He is based in Los Angeles. Stay in touch on Facebook and Twitter.