Question: What do we need to know about markets?

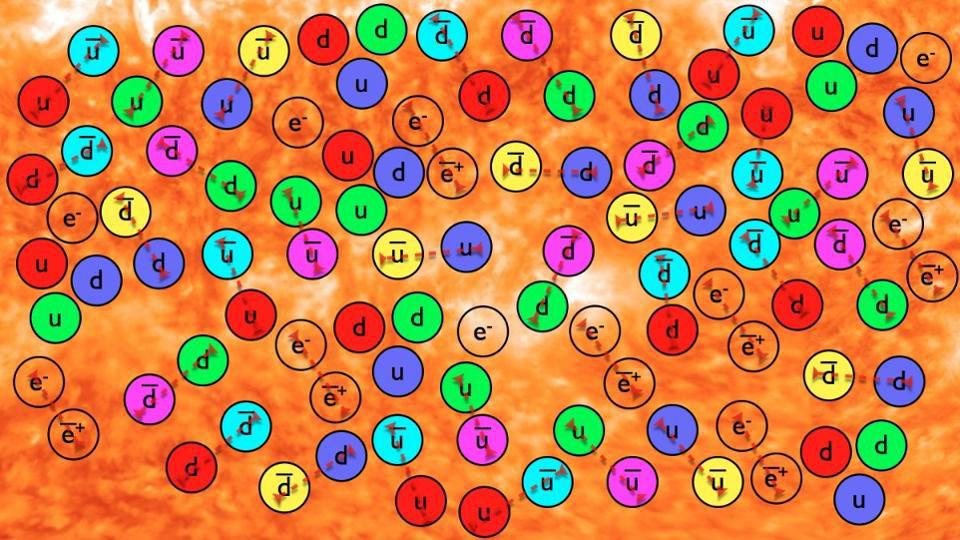

Sally Blount: Economics is the study of the markets. And most sociology also involves the study of markets. Many disciplines take an eye on them. It’s important to remember that all a market is, is a group of like transactions. And all a transaction is, is a buyer and seller getting together. A buyer saying, "I want that." A seller saying, "I don’t want it as much as you want it because the price you are wiling to give me is higher than the price that I need to keep it." And that’s the nature of human commerce going all the way back to the earliest days of human organizing.

And understanding that all a market is an aggregation of people selling and buying similar things and that our models of markets are just that: they’re models. Supply and demand don’t exist. They’re a mode of what we see in every day life that help us understand every day life when we aggregate all those buyer and seller transactions together. And helping students

understand how human society functions, how it naturally self-organizes, which is what a market is, it is what a free market economy is. Because even in the socialist economies and the communists, those markets existed. They maybe weren’t tracked officially, but they were there and they were operating.

And so when I think about how we bring that into education, it’s "How do we help students understand how human organize? We humans interact and bring value to each other?" I love... Adam Smith calls it our propensity to truck. Now obviously, I never thought of that as a verb, and it had meaning back then, but I love that phrase now. Our propensity to truck is what makes us different from the animals. Our propensity to engage in transactions of me to sell you something and you to buy it so that I don’t... you know, you’ll do the farming and I’ll do the selling, and by having this propensity to truck, we’ll each have more well-being in our lives. It’s a very simple principle and I sometimes think that we use words like "markets" and "networks" things. We create an abstraction of reality. These are models of how we exist.

Question: Why is business the dominant social institution of the age?

Sally Blount: Because I look at the world and I see what creates wealth and business by the way for me is organizations and markets, which are both important parts of it. And it’s organizations operating as actors in markets. And I look out at the world and I watch... it’s not the government that’s creating jobs; it’s not the governance that’s creating innovation. It’s not the church that’s doing it. It’s not, you know... you can get something done so much faster with a for-profit business than you can with a not-for-profit or a government or a religious-based business, or even an NGO. And you can move jobs and move wealth and solve problems so much faster, it’s pretty obvious it’s the dominant social institution.

Now do I like that everyday? No. Because sometimes as it’s become the dominant social institution, we’ve allowed market-based logics to dominate our thinking. Part of "How did 2008 occur, how did all your classmates get lured?" as you talked about to Wall Street is because money has become even more motivating to us in the age of the business as the dominate social institution. And money is only a metric. Money is only one place of value in life and if there’s a sort of a challenge that we’re going to have, if we’re going to recalibrate, it’s going to be as a human on a psyche level understanding how much business has come to dominate and homogenize and control culture, in some cases. And making conscious decisions about where we’re going to let that happen and where we’re not.

Right now we’re dealing with the unattended consequences of business emerging as the dominant social institution and we’re beginning to have dialogues about how do we push that monetary metric back a little to let other values on the table as a society, both nationally and globally.

Question: Are markets fair?

Sally Blount: Markets aren’t fair or unfair. Markets create wealth and they’re incredibly efficient at allocating goods and resources and creating surplus for society that makes people better off. But markets have nothing to do with how that well being gets allocated across members of society. And you can’t argue they’re fair or unfair—they’re agnostic. They are amoral; not immoral, amoral. It’s we as human beings who get to decide how much each person should be entitled to on a moral and values-based level. And I personally am somebody who believes the fact that a billion out of the six billion of us on the planet live on what, less than a dollar a day isn’t fair. And I don’t believe that markets can solve it.

I do believe they can create more wealth to spread to help solve it. But if we just allow markets unchecked and somehow argue that will take care of it, I’ve seen no data to indicate that markets will know. Because they aren’t knowing, they’re allocating. They’re generative, not loving.

Recorded October 27, 2010

Interviewed by Victoria Brown