3 advances in philosophy that made science better

- Philosophy is often ridiculed by scientists as being little more than armchair speculation. This is unfortunate because the scientific method itself is a product of philosophy.

- Here, we discuss three major philosophical insights that directly led to advances in how science is performed.

- These insights came from Francis Bacon, Alan Turing, Alonzo Church, and Noam Chomsky.

Philosophy is often ridiculed by scientists as being little more than armchair speculation. Stephen Hawking famously declared it “dead.” This is unfortunate because the scientific method itself is a manifestation of philosophical thought arising from the subdiscipline known as epistemology. Historically, science and philosophy have worked hand-in-glove to advance our understanding of the world. In fact, “science” went by the moniker “natural philosophy” for much of history.

Scientists perhaps should be a bit more grateful. Advances in social and political philosophy helped prevent some scientists who upset the established order from being executed — but that’s a discussion for another day. Here, we will examine three philosophical insights that directly led to advances in how science is performed.

Francis Bacon demands experimental data

“What makes science different from everything else?” is inherently a philosophical question. That means that philosophy helps define what science is. This is important because, to learn about the world, we need to be sure of the validity of our methods. For most of the history of Western philosophy, Aristotle’s ideas reigned supreme. While Aristotle’s idea of finding causes through science was largely based on deductive reasoning, experimentation was not seen as a vital part of science.

Enter Francis Bacon, English philosopher and Lord Chancellor for James VI and I. Unlike many of his predecessors, Bacon believed in the power of empirical data. In his book, Novum Organum (Latin for “New Organ”), Bacon offers an alternative to Aristotelian thought by arguing for the importance of experimental data. While his exact methods are no longer used, his book provides the foundations for the scientific method.

As it turned out, Bacon himself was rather bad at experimentation. (The pneumonia that killed him might have resulted from an experiment in refrigeration involving stuffing dead chickens with snow.) He is sometimes compared unfavorably to Newton, who refined Bacon’s methods and put them to better use. However, his work found an extremely receptive audience during the Enlightenment. Voltaire would go so far as to call him “the Father of the Experimental Philosophy.”

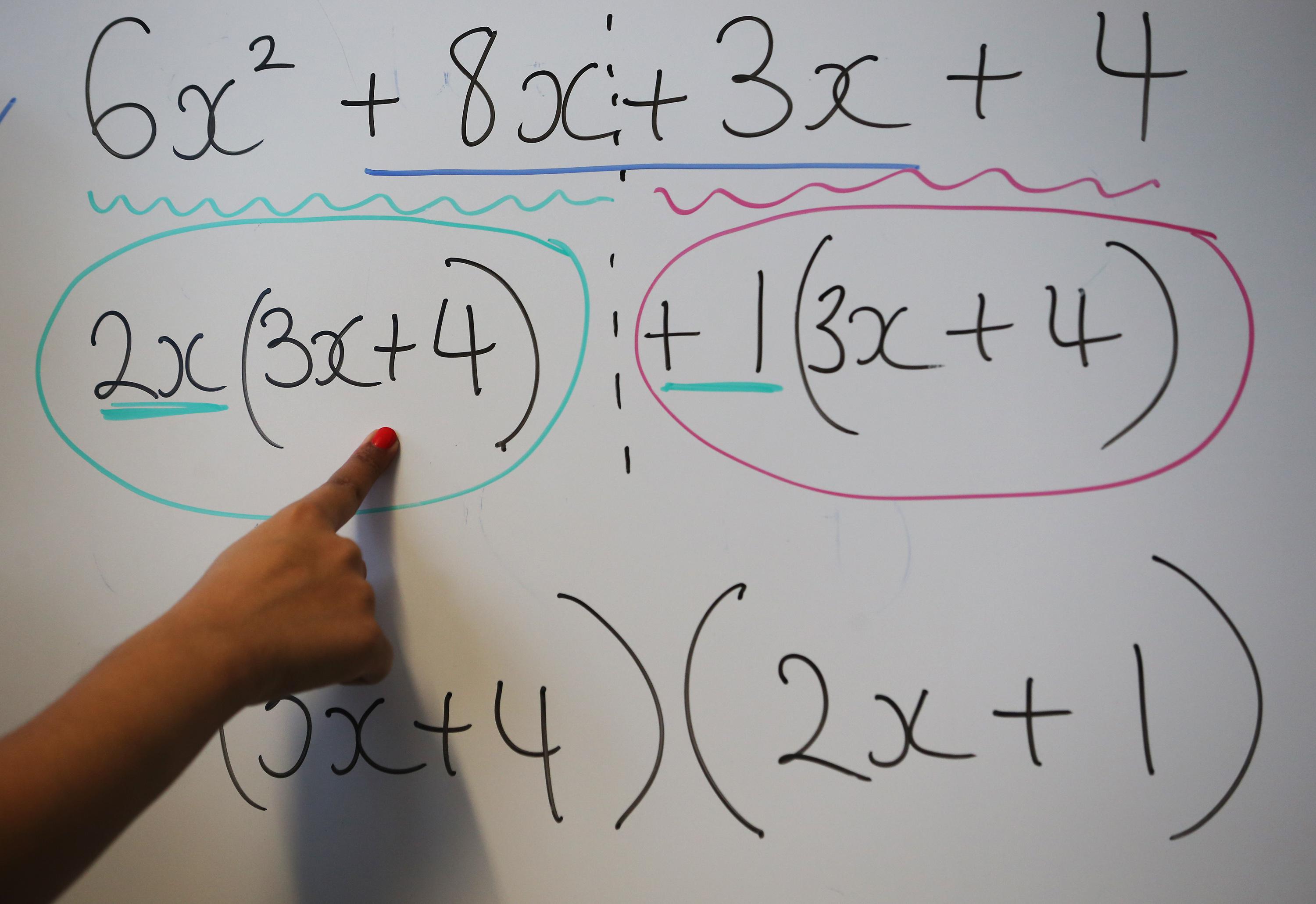

The Church-Turing thesis made computers possible

Modern computing is tied to philosophical attempts to determine what mathematical problems could be solved. While everyone in 1936 knew what a computer was — a human being who computed the answers to difficult mathematical problems — which problems were fundamentally capable of being solved in this way was a more open question.

Alan Turing advanced one solution to the problem in 1936. His world-changing paper has the cumbersome title “On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem.” From this paper, we get many bold ideas, including “Turing’s thesis,” which says that, given enough time, anything that can be represented as an algorithm can be computed. Importantly, he argues that a “universal computing machine” could do this in place of humans.

Less well-known is that Alan Turing wrote his solution to the problem immediately after his doctoral advisor, the mathematician, logician, and philosopher Alonzo Church, wrote his own thesis on the subject. Church’s version is the “lambda calculus,” a method that can simulate all other methods of calculation. The thesis is essentially the same. He also found that anything that can be calculated by a human (or a machine using similar processes) can be solved in a finite number of steps that can be expressed in a limited number of symbols.

Turing’s approach is generally held to be superior — even Church agreed. More importantly, the fact that their work takes different approaches to reach the same answer gave weight to the idea that these unprovable theses were correct. Later arguments would provide further support. Today, the Church-Turing thesis is a basic postulate of computer science that has led to several advances.

Nearly every computer you have ever used is designed as a “universal Turing machine,” meaning that it can execute any algorithm that can be computed. Also, the idea of storing the instructions the computer will follow in an electronic rather than physical format (such as punch code or plugs) also dates back to Turing’s formulation of the thesis.

Noam Chomsky starts the cognitive revolution

In the mid-20th century, many dominant ways of thinking about the mind and brain focused entirely on behavior. Schools of thought, such as behaviorism, centered on human responses to stimuli and punishments. For example, in the case of language, the leading theory in the early 1950s was that children heard large numbers of words and learned to use them by positive reinforcement; when they used them correctly, good things happened.

This theory lost credence after Noam Chomsky wrote his first book. He overthrew the behaviorist model by pointing out that children were not getting enough examples of language in their early years to explain how quickly they learn. Instead, he took an approach similar to that of the rationalist philosophers. He proposed that humans are not born as blank slates but have an innate ability to learn new languages, and he further proposed the so-called “Language Acquisition Device” as a mechanism for this natural and incredible language learning capacity.

While linguists continue to debate the relevance of the original formulation of the theory, it set off the cognitive revolution and directly led to what is now known as the cognitive sciences. The field employs a multidisciplinary approach to understanding the mind that turns the scientific method toward examining what goes on inside the skull. As a result, the cognitive sciences have influenced many aspects of psychology as well as AI.