You don’t see objective reality objectively: neuroscience catches up to philosophy

- Some thinkers propose that it is impossible for us to interact directly with objective reality.

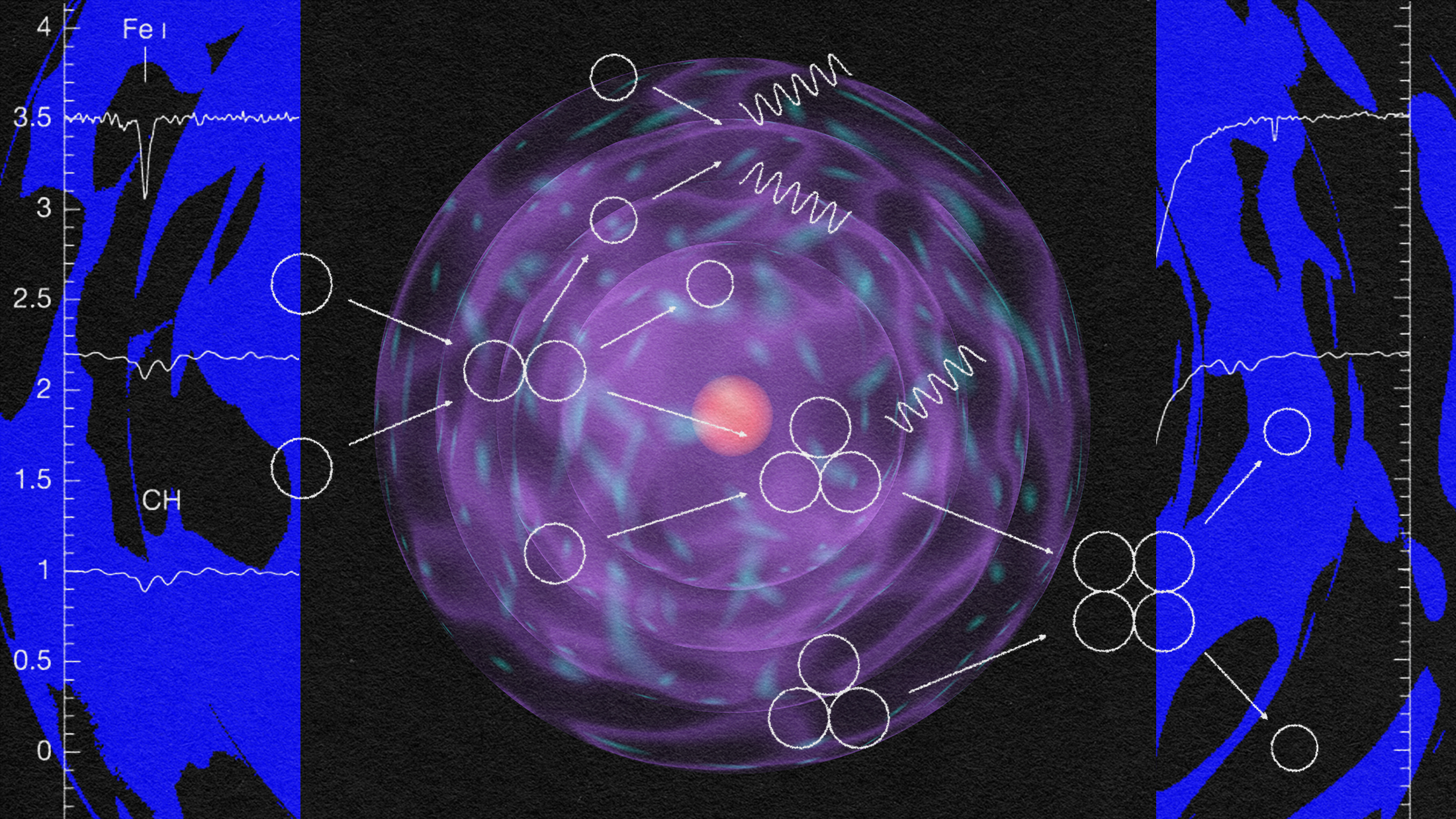

- Studies suggest that our brains warp sensory data as soon as we collect it.

- In the end, it may be best to remember that you do not have perfect information.

Is everything we see but a dream within a dream?

Great thinkers have long wondered whether objective reality actually exists and, if so, whether our physical senses can accurately interpret it. It may be the case that our senses can capture only a small and distorted sliver of the world as it really is. As the problem continues to be debated in modern science and philosophy, advances in neuroscience are offering new insights on the matter.

Is reality an illusion?

You bite into an apple and perceive a pleasantly sweet taste. That perception makes sense from an evolutionary perspective: Sugary fruits are dense with energy, so we evolved to generally enjoy the taste of fruits. But the taste of an apple is not a property of external reality. It exists only in our brains as a subjective perception.

Cognitive scientist Donald Hoffman told Big Think:

“Colors, odors, tastes and so on are not real in that sense of objective reality. They are real in a different sense. They’re real experiences. Your headache is a real experience, even though it could not exist without you perceiving it. So it exists in a different way than the objective reality that physicists talk about.”

Professor of neuroscience Beau Lotto explained to Big Think that the world you see is not necessarily the world that is, because we evolved to view the world in a way that is useful rather than accurate:

“Is there external reality? Of course there’s an external reality. The world exists. It’s just that we don’t see it as it is. We can never see it as it is. In fact it’s even useful to not see it as it is. And the reason is because we have no direct access to that physical world other than through our senses. And because our senses conflate multiple aspects of that world, we can never know whether our perceptions are in any way accurate. It’s not so much: do we see the world in the way that it really is, but do we actually even see it accurately? And the answer is no, we don’t… So at this most basic level, we don’t represent even the information we’re getting in any accurate way. And the reason is because it was useful to see it this way. So what are you seeing [is] the utility of the data not the data.”

This tendency for our minds to bend sensory data in ways that are useful can be seen in a number of instances. One of them is the well-known Thatcher Effect, in which an image of a face (originally one of former British Prime Minister Margret Thatcher) is flipped upside-down and has some features, such as the eyes and mouth, inverted as well. While the switched features are clear to us when the face is made right way up again, it is often impossible to tell when the face is upside-down.

The reasons for this are still the subject of investigation but appear to be related to how our brains handle information related to facial recognition — that is, they are fine-tuned to process information for faces that are right-side-up and not for anything else.

Some thinkers use this idea — that our brains warp sensory input as soon as we get it and put it to use — to question how real our view of reality is at all. Cognitive scientist Donald Hoffman has gone so far as to suggest that consciousness is the primary reality and that the physical world is secondary to it.

A (half-hearted) defense of objectivity

Many philosophers believe objective reality exists, if “objective” means “existing as it is independently of any perception of it.” However, ideas on what that reality actually is and how much of it we can interact with vary dramatically.

Aristotle argued, in contrast to his teacher Plato, that the world we interact with is as real as it gets and that we can have knowledge of it, but he thought that the knowledge we could have about it was not quite perfect. Bishop Berkeley thought everything existed as ideas in minds — he argued against the notion of physical matter — but that there was an objective reality since everything also existed in the mind of God. Immanuel Kant, a particularly influential Enlightenment philosopher, argued that while “the thing in itself” — an object as it exists independently of being subjectively observed — is real and exists, you cannot know anything about it directly.

Today, a number of metaphysical realists maintain that external reality exists, but they also suggest that our understanding of it is an approximation that we can improve upon. There are also direct realists who argue that we can interact with the world as it is, directly. They hold that many of the things we see when we interact with objects can be objectively known, though some things, like color, are subjective traits.

While it might be granted that our knowledge of the world is not perfect and is at least sometimes subjective, that doesn’t have to mean that the physical world doesn’t exist. The trouble is how we can go about knowing anything that isn’t subjective about it if we admit that our sensory information is not perfect.

Science will stop this bickering, right?

As it turns out, that is a pretty big question.

Science both points toward a reality that exists independently of how any subjective observer interacts with it and shows us how much our viewpoints can get in the way of understanding the world as it is. The question of how objective science is in the first place is also a problem — what if all we are getting is a very refined list of how things work within our subjective view of the world?

Physical experiments like the Wigner’s Friend test show that our understanding of objective reality breaks down whenever quantum mechanics gets involved, even when it is possible to run a test. On the other hand, a lot of science seems to imply that there is an objective reality about which the scientific method is pretty good at capturing information.

Evolutionary biologist and author Richard Dawkins argues:

“Science’s belief in objective truth works. Engineering technology based upon the science of objective truth, achieves results. It manages to build planes that get off the ground. It manages to send people to the moon and explore Mars with robotic vehicles on comets. Science works, science produces antibiotics, vaccines that work. So anybody who chooses to say, ‘Oh, there’s no such thing as objective truth. It’s all subjective, it’s all socially constructed.’ Tell that to a doctor, tell that to a space scientist, manifestly science works, and the view that there is no such thing as objective truth doesn’t.”

While this leans a bit into being an argument from the consequences, he has a point: Large complex systems which suppose the existence of an objective reality work very well. Any attempt to throw out the idea of objective reality still has to explain why these things work.

A middle route might be to view science as the systematic collection of subjective information in a way that allows for intersubjective agreement between people. Under this understanding, even if we cannot see the world as it is, we could get universal or near-universal intersubjective agreement about something like how fast light travels in a vacuum. This might be as good as it gets, or it could be a way to narrow down what we can know objectively. Or maybe it is something else entirely.

The objective truth about objectivity

While objective reality likely exists, our senses might not be able to access it well at all. We are limited beings with limited viewpoints and brains that begin to process sensory data the moment we acquire it. We must always be aware of our perspective, how that impacts what data we have access to, and that other perspectives may have a grain of truth to them.

Philosopher Daniel Schmachtenberger told Big Think:

“There is no all encompassing perspective that gives me all of the information about almost any situation. What this means is that reality itself is transperspectival. It can’t be captured in any perspective. So multiple perspectives have to be taken. All of which will have some part of the reality, some signal.”

Fair point, but you may have to worry about if you are actually getting the right information about those perspectives.