America’s workforce desperately needs a data overhaul

A few years ago, I argued that the U.S. is in desperate need of a National Data Service. As I wrote then, the Founding Fathers could not have foreseen the fragility of our national public measurement system, even if they did know that collecting data to determine representation was essential for the governed to have a voice in their government.

The years since have only confirmed the need for a new approach to producing public data. Even the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), a federal agency tasked with producing data to guide Congress, substantially upped Census population figures this year in the development of its own population estimates. The CBO’s revised immigration estimates have significantly affected their projections of population, labor force participation, consumer spending, and personal income, with major implications for government revenue projections. Accurate data are not just important for Congress: The Federal Reserve also relies on both employment and spending data when it makes interest rate decisions that affect vast swathes of the economy, from renters and home buyers to businesses raising capital.

Now, at a more granular level, there is the looming question of AI’s impact on jobs. Is Goldman Sachs correct when it predicts that AI could replace 300 million jobs? Or is MIT economist David Autor correct when he says that AI will help low-wage workers? Understanding AI’s impact on jobs is crucial for shaping policies that ensure economic stability and workforce readiness.

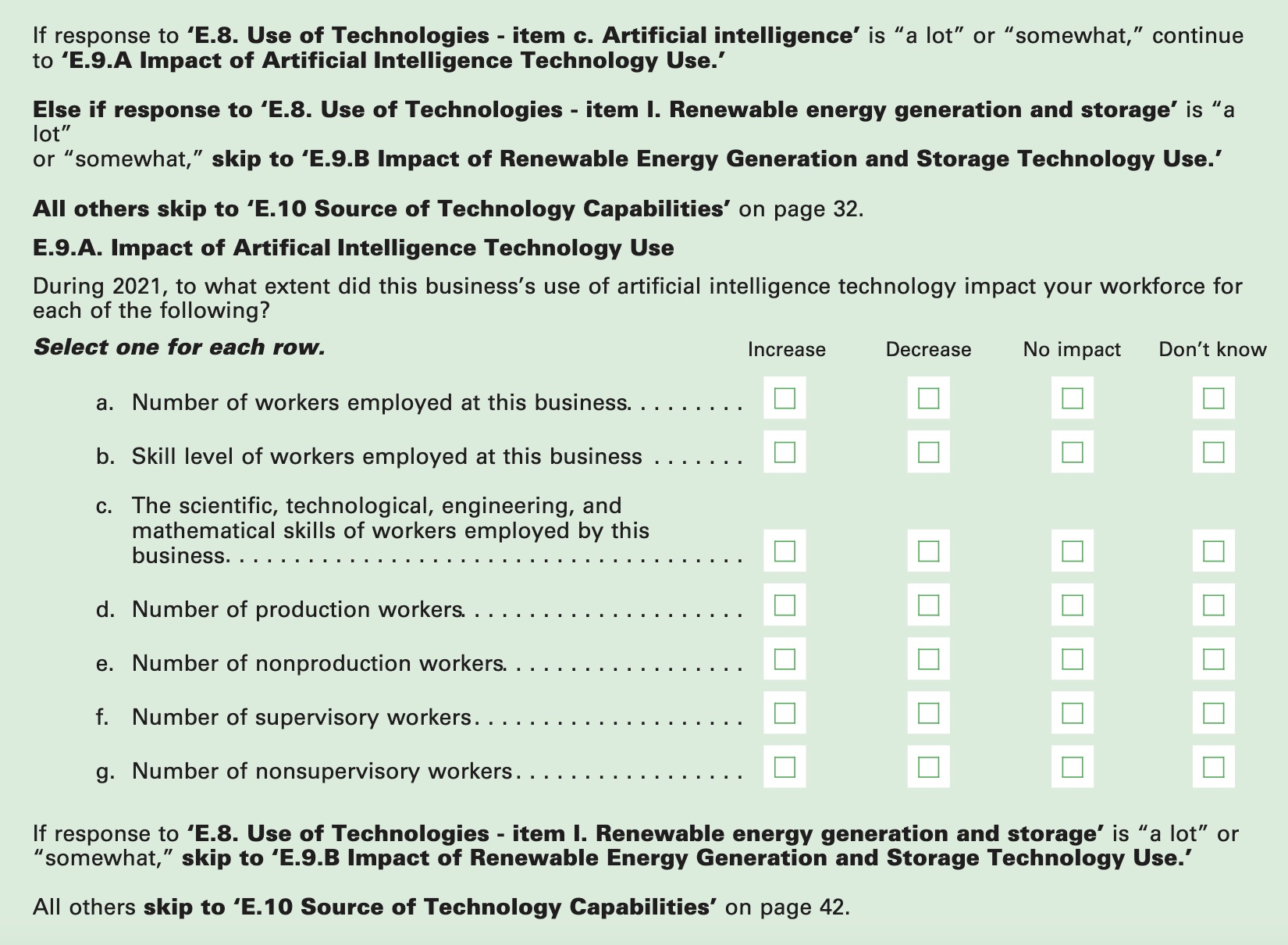

The bad news is that Census data are no better for AI than for the population estimates. The Census Bureau’s approach is to survey businesses using archaic methodology, essentially relying on an administrator in a firm to answer questions about the impact of AI as part of a 52-page survey on their business. It’s no surprise that the figures from a recent Census Bureau report reflect such a low rate of AI use in firms — less than 5 percent, and even lower in a “snapshot” survey.

Yet, as with population data, accurate and timely data on AI’s impact on jobs is essential for a thriving economy. Jobs are the bedrock of our communities, and local labor markets are where businesses connect with workers and people find opportunities. Unreliable information about job trends can have devastating consequences for both employers and employees.

A recent survey underscores the urgency of this issue: 64 percent of students graduating in 2027 say AI has already influenced their academic plans. Yet these students are making critical educational investments based on potentially outdated or inaccurate information about future job prospects.

We cannot afford to repeat the mistakes of the past, such as when we overlooked the impact on rural America of lost manufacturing jobs, and failed to enact policies that could have cushioned the blow. To build a prosperous future, we need local, timely, and actionable data that empowers individuals to make informed career choices and businesses to thrive.

As I have consistently argued, new data, evidence, and statistics need to be created outside of government. There are so many good people working in the federal government, but the bureaucracy can’t be as agile in hiring and paying the right people, in upgrading its computing infrastructure, and in getting approvals and funding. For fast-moving areas such as AI, private and nonprofit sectors outside of government need to take the lead on innovation and let the government benefit by later incorporating what is learned into the data series they produce. A new and independent entity must be established.

It is increasingly clear that this should be a new Center for Data and Evidence that is outside the federal government. The Center should be designed to ensure that the results are modern, flexible, and driven by demand. It should be responsive to the incentives that are lacking within the current federal data system so that it can respond to new needs. That means that the new Center should be independently funded and non-partisan, charged with securely hosting data and supporting programs and research with bottom-up, demand-driven tools and insights for businesses, workers, and governments.

Many successful institutions have set precedents. Take, for example, the highly respected Urban Institute and MDRC. Each institution was established with joint funding from a government agency and philanthropic foundation to do independent research and analysis. While the funding structure might be similar, the design of the Center would reflect our new reality. Such a Center would:

Use modern data — The center should begin with getting better data on the impact of AI on jobs. Businesses post thousands of listings every day about available jobs, skill needs, and salary ranges. Workers post thousands of resumes every day about their skills, experience, and desired salaries. By analyzing job postings and resumes, the Center would provide localized insights for businesses, workers, and policymakers. This data would help businesses optimize location and wages, empower workers to acquire in-demand skills, and enable policymakers to allocate training funds effectively. State-level initiatives in New Jersey, Arkansas, and Texas have already laid the groundwork.

Make sure the data are right — Data from multiple sources must be vetted and standardized. The center should support a consortium of stakeholders to design and introduce universal data structures and metadata, develop common legal frameworks, establish core technology standards, and create privacy protection processes that can rapidly simplify and professionalize the access to and use of new sources of data across the nation. Tools that are developed should be held to meet those interoperable standards so that the best ideas can be reproduced and scaled across the country.

Bring together the best minds in the world — The Center should bring together the best minds in the world through fellowships, training, and competitions. Their initial charge should be to describe the impact of AI on jobs for workers, businesses, training providers, and legislators. They would be charged with producing open-source tools to build cutting-edge data and reproducible, replicable analysis — like the Underwriters Labs for the public good. The foundations for such an infrastructure already exist. The Institute for Research on Innovation and Science has built a prototype system that measures the economic impact of federal investments in research and technology. The National Data Platform, established jointly by the San Diego Super Computer Center and the University of Utah’s Scientific Computing and Imaging Institute, and funded by the National AI Research Resources pilot, was designed to support a national federated data ecosystem with modern workflow tools and equitable access.

Be demand-driven — Although it might start with AI and the jobs market, the Center should be designed to respond to changing demands and high-priority needs. Fellowships, advisory groups, details, or training classes can all be ways of bringing new people and ideas to develop new tools and measures in ways that are useful, transparent, explainable, interpretable, and fair.

Good data can provide signposts for policymakers to chart paths in which AI leads to good jobs, not lost jobs. It is now possible to track the impact of AI on jobs by tracing AI investments in university research to firms’ hiring. It is now in the realm of possibility to produce high-quality, timely, local, and actionable data to ensure that the massive demand shocks, such as the Chips and Science or Inflation Reduction Acts, lead to higher-wage, more stable jobs. This involves monitoring earnings, employment, and skill demand for AI research-intensive employers. Such data can strengthen federal policymaking by informing the use of the best data, measures, and methods.

As the economist Herb Stein said, “If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.” We’re close to the stopping point. The current data system is archaic, expensive, and in crisis. We cannot continue making decisions blindly. The new center will require new investments, but in this situation, building new is likely to cost substantially less than relying on the antiquated alternative. Most importantly, the value of developing modern, flexible, trustworthy and accessible foundations is incalculable to furthering the prosperity of our nation and individuals’ opportunity to achieve the American Dream.

Julia Lane is a Professor in the Wagner Graduate School of Public Service at New York University. She has co-founded or co-initiated a number of national public data infrastructures, including the LEHD program at the Census Bureau, and served on the National AI Research Resources Taskforce. She is the author of “Democratizing Our Data: A Manifesto.”

This article was originally published on MIT Press Reader.