National parks are great. Now, let’s create a World Park

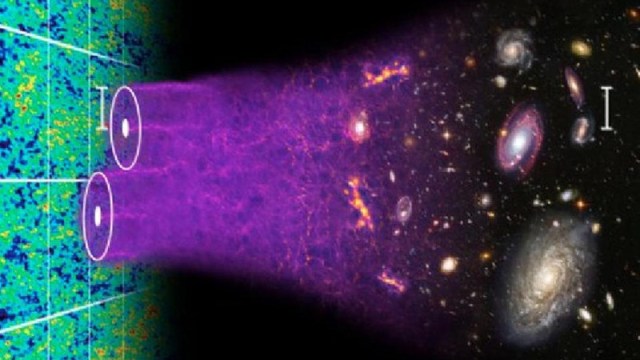

Credit: Richard Weller / University of Pennsylvania

- America’s system of national parks is among the best ideas that the country ever had.

- While they are a remarkable achievement, they are not representative of all biodiversity that exists, and they are not connected to each other. We must physically connect them so ecosystems can adapt to climate change.

- Constructing a World Park that connects global protected areas could be achieved with as little as $7 billion.

105 years ago this month (August 25), President Wilson signed the act creating the National Park Service, a new federal bureau of the U.S. Department of the Interior. Often referred to as “America’s best idea ever,” national parks date back to the 19th century with the protection of Yellowstone and Yosemite. The idea has since been embraced by other countries, resulting in what are known as Protected Areas overseen by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), headquartered in Gland, Switzerland. What began as 3,471 square miles in Yellowstone in 1872 now amounts to 12.5 million square miles in over 202,000 different locations across 196 nations. About one-fifth of the earth’s dry land is protected from destructive human activity.

By any measure, this is a remarkable achievement for the global conservation movement, and it is widely accepted that protected areas, if well managed and inclusive, are not just beneficial (to our physical, emotional, and spiritual wellbeing) but necessary. In scientific terms, biodiversity is invaluable: without it, entire ecosystems would collapse and, in all likelihood, take humankind with them.

But the protected areas we have today are woefully inadequate because they are not “representative” and they are not “connected.” That is to say, they do not represent the world’s actual range of critically endangered biodiversity, and they are not connected in a way that would allow species to migrate so as to adapt to climate change. Without being expanded and interconnected, today’s protected areas represent big, isolated zoos, and climate change threatens to leave many of the species trapped within them, with little hope of adapting to rising temperatures.

From national park to World Park

Our best hope to halt or even reverse the loss of biodiversity, as well as make the work of conservation and land management more inclusive, is a new form of conservation landscape suited to the 21st century: the World Park. A World Park would bring nations, states, landholders, and indigenous custodians together in a cooperative effort to create continuous tracts of restored habitat for both recreation and the protection of endangered species. It would direct global conservation investments and commitments into one coordinated initiative, rather than perpetuating the ad hoc collection of protected areas we have today.

In thinking seriously about how a World Park would really work, the first question to ask is: where should it be located? The answer is determined by the location of the world’s 36 so-called “biodiversity hotspots.” These are regions of unique (endemic) biodiversity threatened with extinction that the scientific community generally agrees should be prioritized in conservation efforts. Wherever possible, the world park would amalgamate as many of these hotspots as it can into a single contiguous landscape. Within the hotspots, park land is then designated by identifying the land needed to forge connections between the existing fragments of protected areas. This land is typically wasteland or pasture or crop land, and the World Park’s mission would be to restore this land to ecologic health.

How, then, do we make the World Park a reality? There are two simple answers. The first concerns walking and the second working. From a design perspective, the simplest and cheapest catalyst for the beginning of the World Park is to create a series of trekking and cycling trails that demarcate and provide access to the park’s territory. As proposed, the World Park includes three recreational trails: the first from Australia to Morocco, the second from Turkey to Namibia, and the third from Alaska to Patagonia. These three trails pass through 55 nations and 19 biodiversity hotspots and link together many of the protected areas in the hotspots.

The trails are not only for trekking, but they also would encourage people to stop en route and join a World Park Rangers program to work on restoring the ecological health of the landscapes through which the trails pass. The World Park Rangers program would operate similarly to the way the Peace Corps does today and the way in which the Conservation Corps did during the U.S. New Deal in the 1930s.

Of course, things quickly get more complicated when we ask how to finance and govern a World Park. The 55 nations and their indigenous peoples and landowners whose territory is incorporated into the park’s jurisdiction as we have mapped it would need to work this out. Other nations may also contribute through global carbon markets and particularly through youth involvement in the World Park’s landscape restoration programs. In addition to nation-states, the world’s environmental and conservation NGOs would also need to be on board with the project and have a seat at the table concerning its administration and the science underpinning its program of works.

Regarding cost, the environmental analyst and former head of the World Watch Institute and the Earth Policy Institute Lester R. Brown has calculated that to restore 10 per cent of the world’s degraded lands — factoring in the cost of seedlings, labor, retiring agricultural land, and fixing erosion — would cost around $50 billion. Because it is mainly about connecting existing protected areas, the World Park’s actual land area is more like only 1 per cent of the world’s terrestrial area.

Low cost, high impact

Factor in the trails, campsites, field stations, related infrastructure, administration, and research, then World Park is, say, a $7-billion project. Could it be that for a mere $7 billion we could create something that would help solve two of conservation’s biggest problems — landscape connectivity and ecological representation? Could it be that for a mere $7 billion we could provide meaningful experiences and jobs for legions of the world’s youth? Could it be that for a mere $7 billion we could create something that transcends national borders and prioritizes the long-term fate of the earth’s biodiversity over selfish short-term interests? Could it be that for a mere $7 billion we could create a profound sign of hope that humanity can work together to be a constructive force of nature? Imagine that.

Richard Weller is the Meyerson Chair of Urbanism, professor and chair of landscape architecture, and co-executive director of The Ian L. McHarg Center for Urbanism and Ecology at the University of Pennsylvania.