How Traveling Abroad Changes Your Outlook on the World for the Better

When the term “armchair” is applied to a job title, it’s almost always derogatory. An armchair general, for example, refers to someone who considers himself an expert on military matters even though he’s never seen combat, or perhaps even served in the military. It implies a critical lack of real-world experience.

Considering that the United States remains the world’s only superpower, that begs the question: How informed are Americans when it comes to their country’s vast global power?

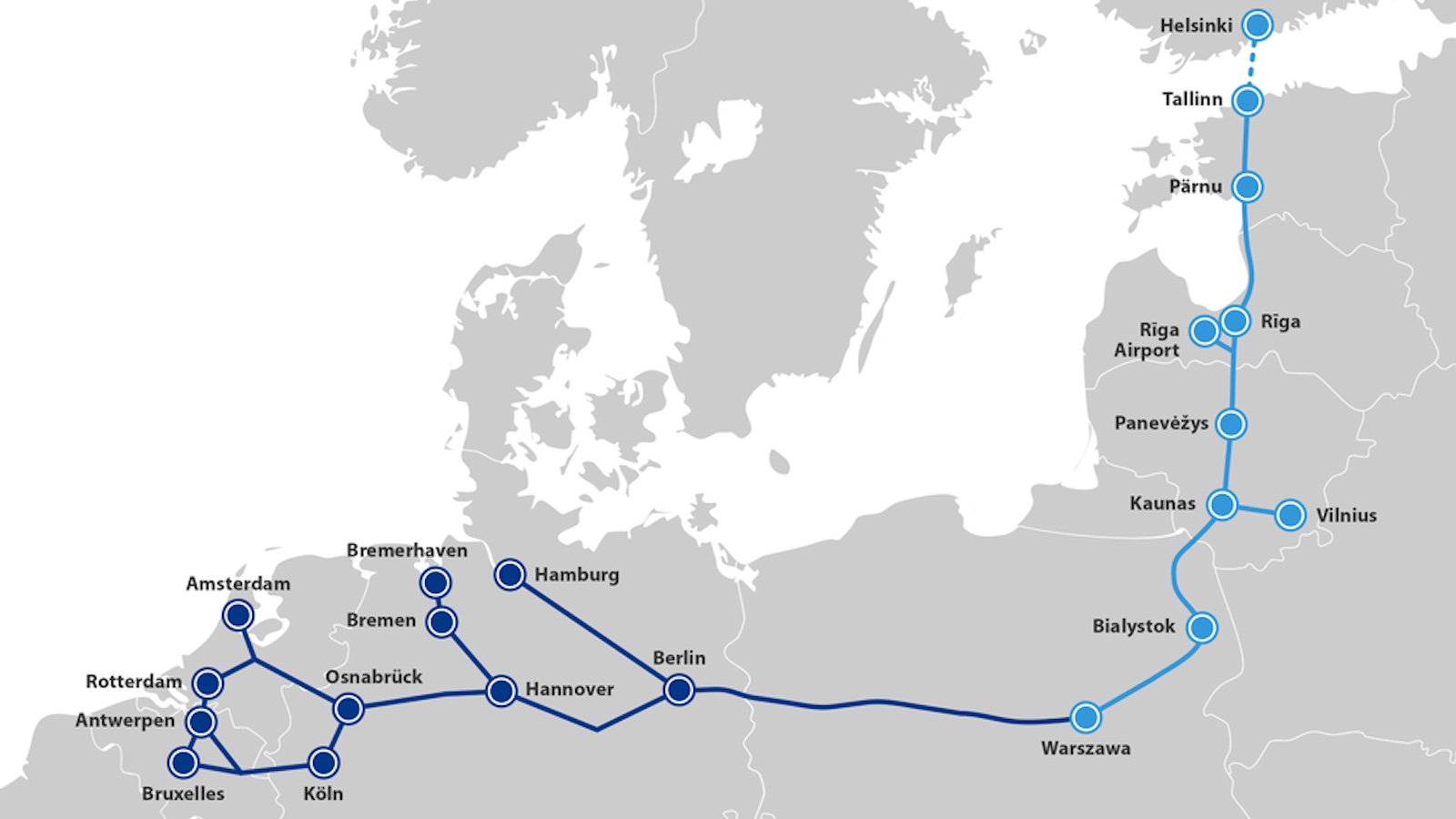

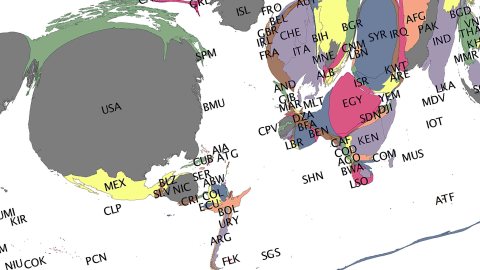

Map of U.S. military bases around the world, from Politico.

You might think that reading daily newspapers or staying glued to Twitter would produce an accurate view of our world, run by 195 different countries over 57 million square miles of land. But a study of news coverage across the globe reveals how erroneous that assumption is.

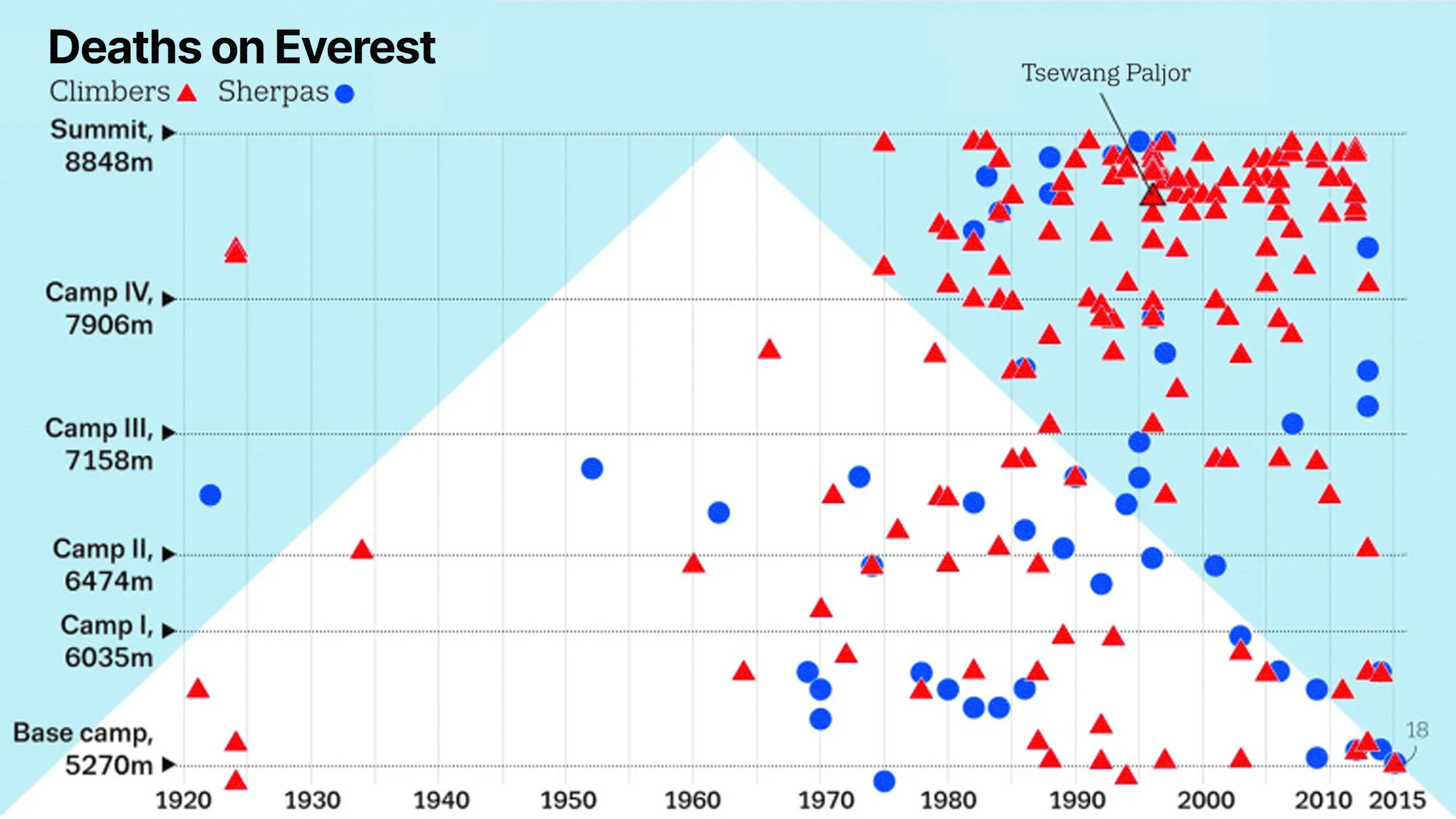

In 2014, Haewoon Kwak and Jisun An at the Qatar Computing Research Institute in Qatar analyzed thousands of real-world events and news articles, and then created a map of the world that shows each country distorted in size by how much coverage it receives in a given region. The bigger the country appears on the map, the more news coverage it receives.

News geography seen from North America.

Compare that with global news coverage from Europe and Central Asia.

Finally, compare that to news coverage in East Asia and the Pacific.

While a region’s news media provide a sample of world events, it’s important to remember that they can’t capture the whole story. Many world events—even whole societies—fall outside mainstream news coverage.

If you had read a newspaper article about the Battle of Dunkirk during WWII, for instance, your understanding of the event would depend on the country in which you lived. Britain successfully evacuate some 330,000 fighters surrounded by Germans troops—nearly 10 times the number Churchill expected to save. In terms of casualties, however, the Germans beat the British Army by a factor of two.

On June 1, 1940, the New York Timesreported:

“So long as the English tongue survives, the word Dunkirk will be spoken with reverence. In that harbour, such a hell on earth as never blazed before, at the end of a lost battle, the rags and blemishes that had hidden the soul of democracy fell away. There, beaten but unconquered, in shining splendour, she faced the enemy, this shining thing in the souls of free men, which Hitler cannot command. It is in the great tradition of democracy. It is a future. It is victory.”

But Berlin’s Der Adler, a Nazi biweekly, had this to say:

“For us Germans the word ‘Dunkirchen’ will stand for all time for victory in the greatest battle of annihilation in history. But, for the British and French who were there, it will remind them for the rest of their lives of a defeat that was heavier than any army had ever suffered before.”

Asking who won the battle is a simple question. But the answer is more nuanced. And having nuanced answers to global questions has never been more needed. To better understand how international travel producers a fuller worldview, Big Think asked three experts in the field of foreign policy about experiences that shaped their outlook.

Stephen Walt, professor of international affairs at Harvard University:

“When I lived in Berlin in the mid-1970s, I watched the May Day parade in East Germany and visited a number of museums there. I was struck by how the history young East Germans were learning and the history I had learned in the West were quite different, and over the years I came to understand what I thought I knew was not in fact 100 percent correct. Of course, neither was the Communist version. It taught me that different peoples often see the world differently because they have been exposed to competing historical narratives, and that insight has remained with me ever since.”

Amaryllis Fox, former clandestine service officer for the Central Intelligence Agency:

“I’ve hosted discussions all over the world between former fighters, from national armed forces to insurgents and terror groups. But no matter how often I witness it, the magic never fails to move me. It’s quite literally like watching a curse be lifted in a folktale. Two groups of people who have always viewed the other as a two-dimensional caricature, hearing one another express the same fears and insecurities and hopes and dreams that they themselves feel and share. Each person hits a different point where they get this look on their face, blink a couple of times, as though some sleeping spell has just been lifted and they can see clearly again after a very long hypnosis.”

Will Ruger of the Charles Koch Institute, a philanthropic organization encouraging discussion on topics like free speech, foreign policy, and criminal justice reform:

“Foreign travel provides a lot of benefits, including getting to better understand other cultures. But it also allows one to better appreciate that despite all of the ways that the world is “smaller” and more interconnected today, the world is still a big place, the U.S. is still very far away from most hotspots and the major industrial areas of the world, and that not everything that happens in the world directly impinges on American interests or depends upon the U.S.”

My experience abroad in the U.S. military (both on active duty in the Middle East and as a reservist in places like Europe and South Korea) has really driven home just how massive is the size and scope of our defense establishment. It is one thing seeing maps marking the many U.S. bases around the globe to seeing up close and personally how big our footprint has been in places like Kuwait and Afghanistan. It has also impressed upon me how well the U.S. military does logistics relative to other militaries today and throughout history.”

The world is a big place, and understanding it is made harder by the fact that there really isn’t one single overarching narrative of world history — at least not one that everyone agrees upon entirely.

Perhaps most importantly, traveling the world can provide a firm understanding of what it means for the U.S. to use military force abroad. If you actually set foot in another country and talk with the people, you’ll have a better sense of how future U.S. intervention might affect that country would than you would, say, if you had only watched network news.

How might Americans think differently about U.S. foreign policy if more people traveled — if more people experienced new cultures, food, people, cities, and histories, finding not just strange differences, but fundamental similarities?

There’s only one way to find out.

—