Bathrooms didn’t exist until the 19th century

“Going to the bathroom” is a ubiquitous euphemism for using the toilet. But, as historian Alison K. Hoagland explains, the current norm of having the bathtub, toilet, and sink all in one room is a relatively new thing. Drawing on her own visits to old houses in the copper mining towns of northern Michigan, she tells the story of how working-class American homes gradually acquired bathrooms.

For the upper classes, Hoagland writes, plumbed-in amenities arrived piecemeal in the nineteenth century. Sinks were installed first in bedrooms, as a replacement for the pitchers of water and basins that had previously been ferried in and out by servants. Bathtubs and toilets each got their own rooms—with toilets placed farther away from living spaces due to the smell.

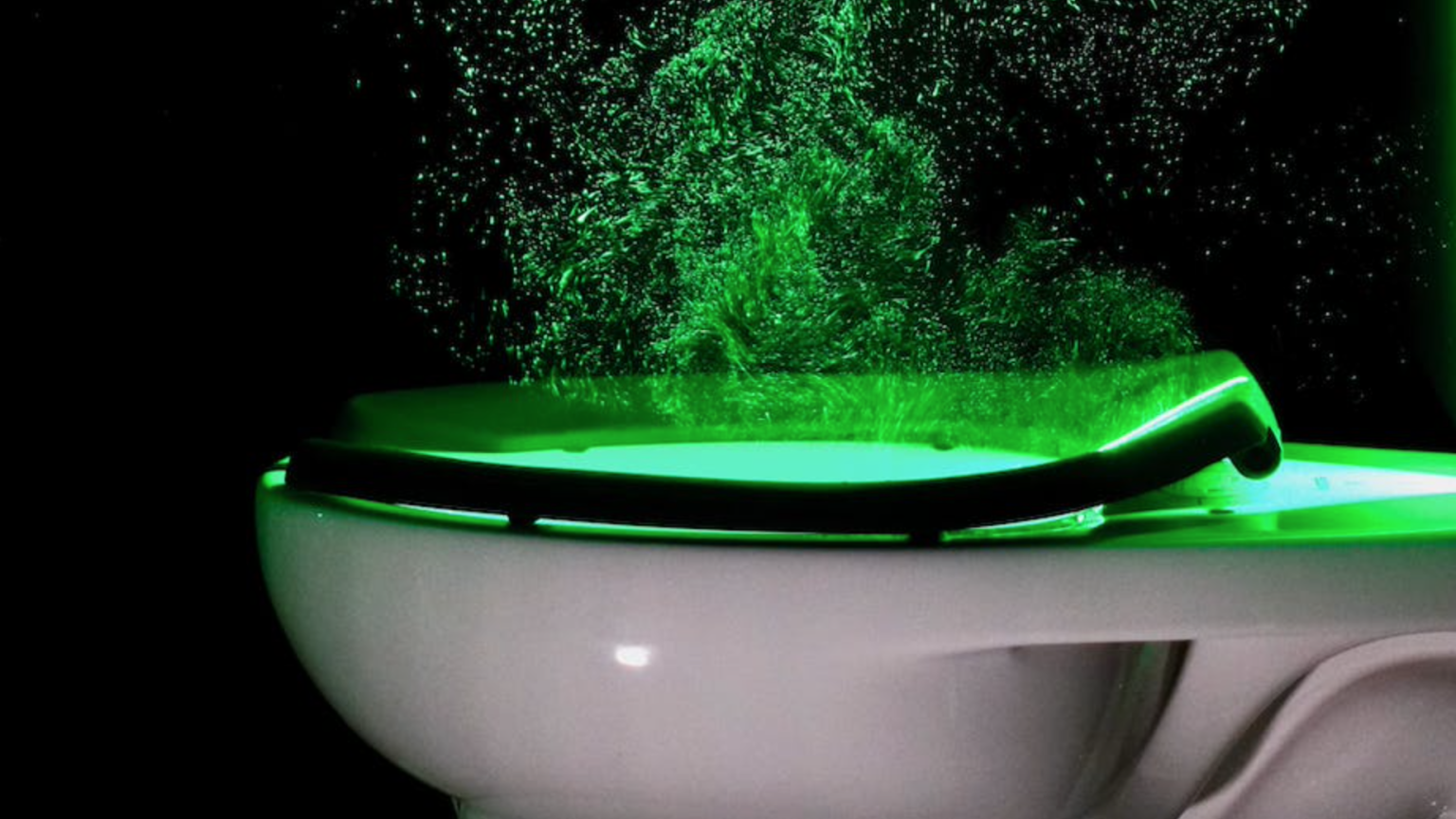

Starting in the 1870s, health professionals urged architects to place all three fixtures together to reduce the mess of pipes and traps running through the house. Builders delicately decided to name the resulting room for the bath rather than the toilet, and by the 1880s, the term “bath room” or “bath-room” was common.

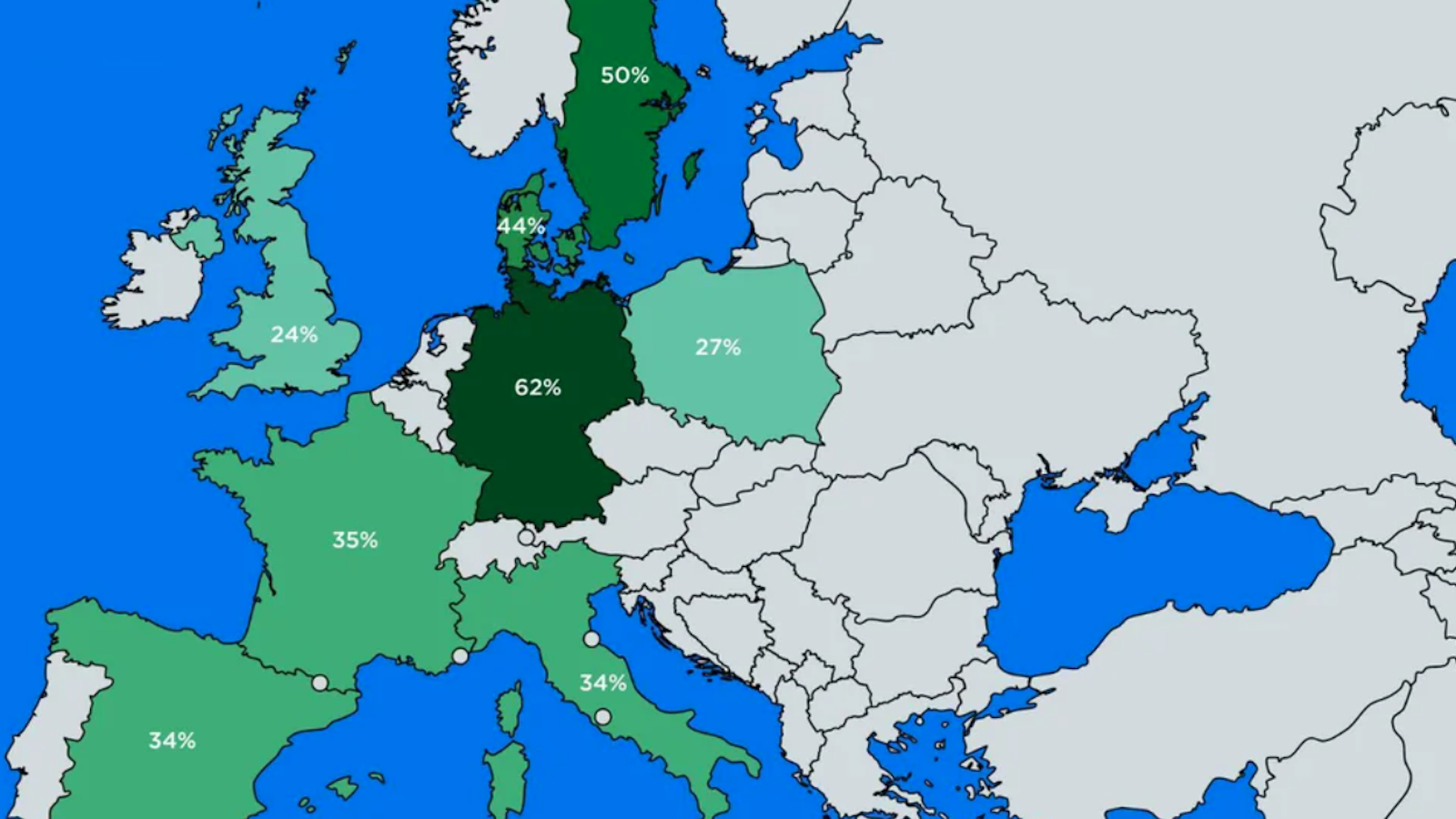

Middle-class homeowners gradually followed the wealthy, adding “bath-rooms” to existing homes or buying new ones that included them from the start. But few working-class families could afford to buy new homes, and retrofitting buildings to add bathrooms was expensive too. So, like the wealthy decades earlier, but for different reasons, they placed fixtures in different places throughout the home.

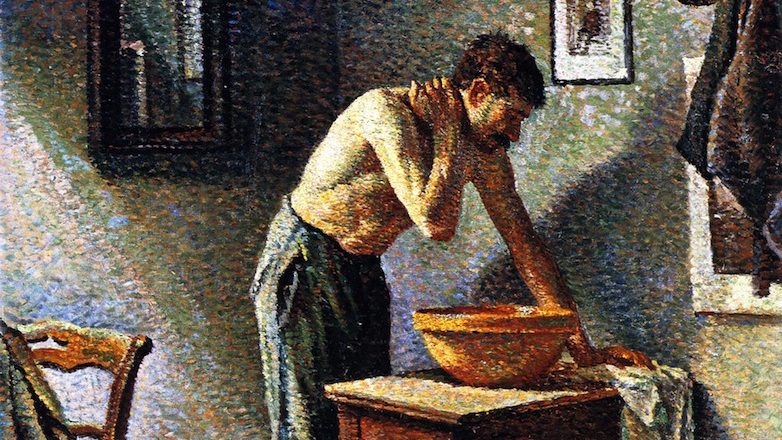

For most working-class homes, the first fixture was the kitchen sink. Even without indoor plumbing, these could be filled using buckets and drained with pipes that emptied out under the house or in the yard. Once a home got running water, the kitchen sink could also serve for washing, toothbrushing, and shaving.

As bathing became a middle-class norm over the course of the nineteenth century, social reformers attempted to bring baths to “the great unwashed.” But even those working-class families with the resources and desire to build their own bathing facilities didn’t necessarily follow the pattern of the rich. Hoagland points to some Finnish-American miners who built family saunas used for childbirth, folk therapies, and laundry as well as bathing.

Meanwhile, before indoor toilets, working-class households used outhouses and chamber pots. In one case Hoagland points to, men simply urinated into the yard from a window. Toilets were more difficult to install than sinks or tubs—drainage pipes needed to connect to cesspools or sewer systems to avoid threats to health. In Michigan, where the climate made frozen pipes a danger, they were often installed in dirt-floored basements—which, in some cases, meant that going to the toilet required a descent through a trapdoor.

Eventually, most working-class houses did get their own dedicated three-fixture rooms. Many of the miners’ homes Hoagland visited were retrofitted after World War II, with bathrooms squeezed into spaces broken off from a kitchen or dining room, or expanded from basement toilet rooms with staircases added for convenience. At long last, miners and their families could literally go to the bathroom.

This article appeared on JSTOR Daily, where news meets its scholarly match.