Scientists watch broken metal heal itself

On a recent sunny day in North Carolina, Jeremy Wagner watched his kids enjoy one last ride. Waiting in the parking lot, near the Carowinds amusement park entrance, he had a commanding view of the big roller coaster, the Fury 325. Wagner’s kids had already ridden it a handful of times, going as fast as 95 miles per hour—but this time the father noticed something peculiar: a crack. One of the steel support beams seemed to swayevery time the passengers zoomed by a turn. Wagner started recording the coaster on video, and when he saw daylight shining through that fracture, he scrambled to plead with the park’s staff to shut the ride down. They seemed indifferent, Wagner told the Washington Post, but after his video went viral, Carowinds took the Fury 325 offline and ordered a new replacement beam.

But what if no replacement beam were necessary? It might seem like a fanciful hypothetical—to wonder whether you could build a roller coaster with metal that could, say, heal itself, obviating the need for repairs. CBS News later reported that cracking in the Fury 325’s beam was visible up to a week before Wagner’s visit. What if the metal could have started mending itself as soon as it began to split? It’s not beyond the realm of possibility.

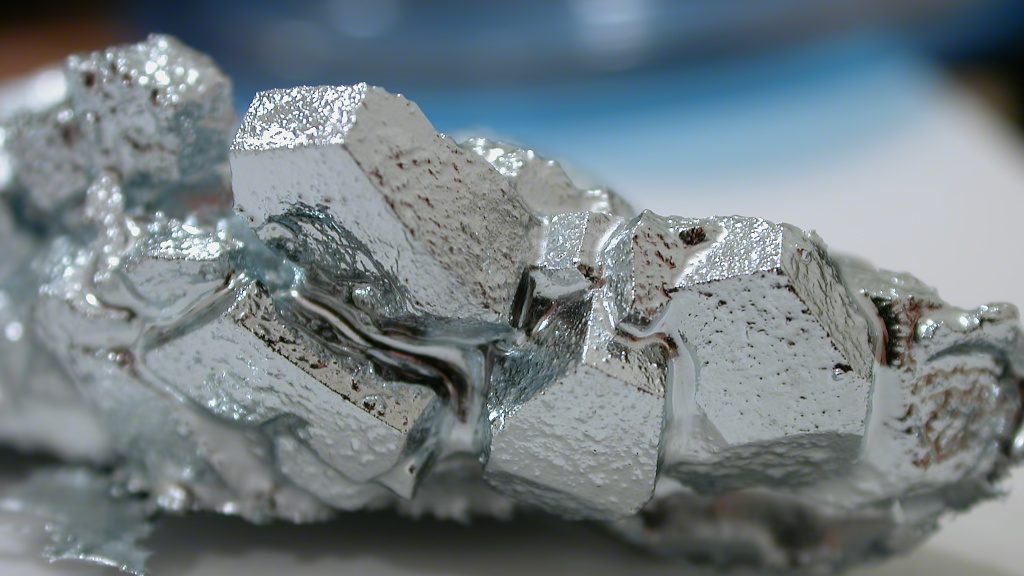

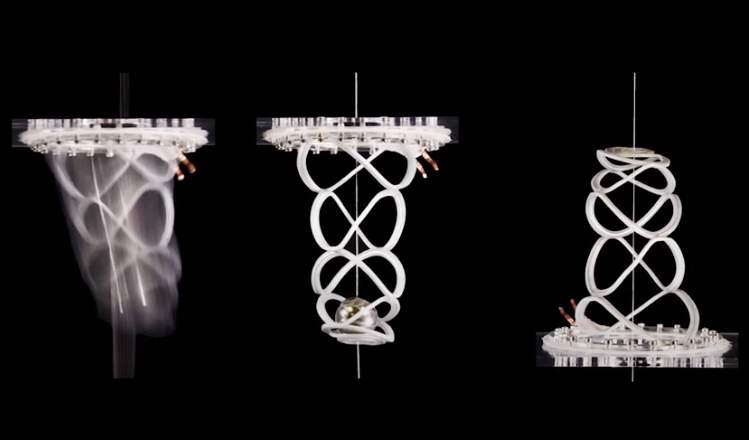

At least, that’s what researchers from Texas A&M University and Sandia National Laboratories claim to have observed in a new study published in Nature. Under a powerful microscope, they watched as a “fatigue crack”—the sort of slowly developing fracture the Fury 325 suffered—healed on its own in a thin (40-nanometer thick) sheet of platinum foil, a metal used in the manufacture of jewelry and in microelectronic devices. “This evidence that pure metals may occasionally heal themselves at the nanoscale is astonishing,” they write.

The findings have implications for how we assess wear in metal structures, as well as for how we might design new fatigue-resistant materials. Fatigue cracks are one of the principle ways that machines break down. Repeated stress causes microscopic cracks that grow over time, leading devices such as car engines, electronic devices, airplanes—and roller coasters—to fail. Scientists have created some other self-healing materials already, mostly plastics, but did not believe such processes were possible in metals until about a decade ago. In 2013, Michael Demkowicz, currently a professor at Texas A&M University, led a study that first theorized the possibility that metals could self-heal.

In the new study, the researchers found that platinum foil could heal itself through a process called “cold welding”—a kind of welding that doesn’t involve heat from a torch or external pressures. In a simulation of nano-scale cracks in metal, the researchers found that what drives welding is “a combination of local stress state and grain boundary migration.” The level of stress a metal undergoes around a crack’s tip can differ from the stress elsewhere. This affects the crack’s behavior, helping to determine whether it’ll grow or heal. The metal’s grain boundaries matter, too: Metals are made up of lots of tiny crystals, or grains, that are bonded together at their borders, and these can move, changing their positions within the metal depending on various factors, including mechanical stress. The fact that metals can apparently mend themselves, the researchers write, “challenges the most fundamental theories on how engineers design and evaluate fatigue life in structural materials.”

Will this discovery change the way we build roller coasters? It’s too early to say. The researchers concede that it may be “tempting to discount the present observations of fatigue crack healing as a rare or anomalous single event” enabled by their specific experimental conditions. But they believe their findings show that autonomous healing could work for a variety of metals. While they experimented directly only with platinum foil, they created atom-level simulations of the crack healing process in other metals. “This phenomenon is not peculiar to platinum,” they write.

One glaring obstacle to a self-healing metal roller coaster—or electronic device, vehicle engine, airplane, or bridge—is the fact that metal doesn’t seem to heal as quickly as it cracks. So the sort of cold welding the researchers observed could only slow the spread of cracks rather than eliminate them altogether. At growth rates of approximately 10−6 meters per cycle, they write, “fatigue striations on metallic fracture surfaces provide evidence that the crack grows on each cycle with no evidence of healing.” By “cycle,” the researchers mean a repeating stressor, like the strain the Fury 325 roller coaster was putting on the beam as riders went around and around that turn Wagner eyed.

The father, a season-pass holder, harbors no grudge against the amusement park. Wagner’s confident the engineers will fix the attraction. “It might even be better,” he told the Washington Post, “safer than it was before.” An old-fashioned fix will have to do—for now.

This article originally appeared on Nautilus, a science and culture magazine for curious readers. Sign up for the Nautilus newsletter.