culture

Be more like Goldilocks.

People who’ve never been partnered tend to be less extraverted, less conscientious, and more neurotic.

A survey of more than 6,000 of the world’s richest, most influential people shows that 9% of them attended Harvard University.

Will “Sausage Party” survive the test of time?

From Einstein to Twain, Garson O’Toole investigates the truth behind your favorite — and often misattributed — quotes.

From tribal hunts to Stonehenge and into the modern day, the peer instinct helps humans coordinate their efforts and learning.

Studying why innovation clusters form can shed light on how to better promote research and growth.

Plenty of parents feel guilty about wanting to skip playtime, but there’s no need.

Meet the scientist mixing mentalism with principles from positive psychology and the science of human potential.

“No matter how long you’ve been doing a job or how good people say you are, you need to care as if you’ve never done it before.”

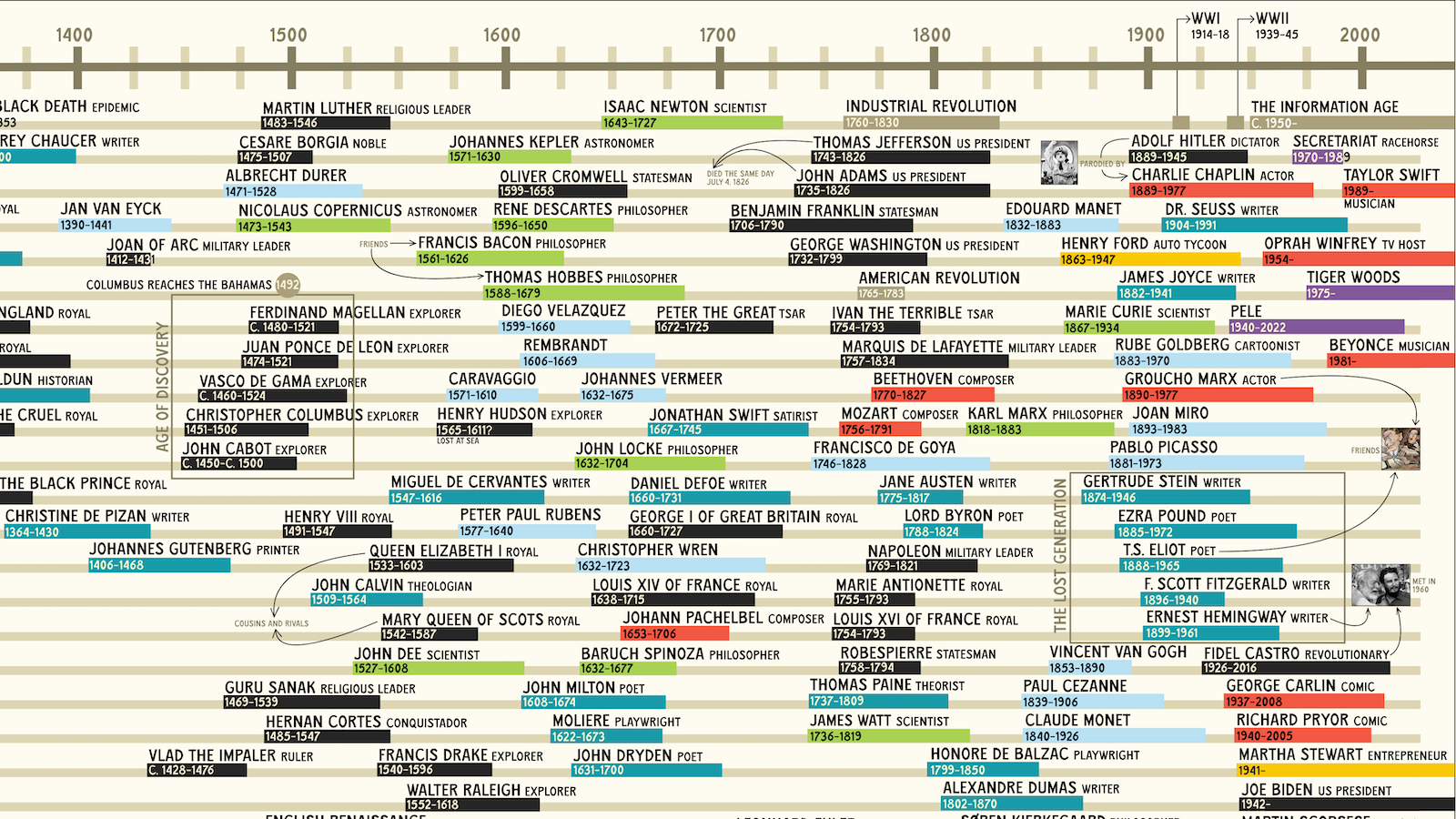

“The Big Map of Who Lived When” plots the lifespans of historical figures — from Eminem all the way back to Genghis Khan.

The annual rite of passage has always been more about the ambivalence of adults than the amusement of children.

Dennis “Thresh” Fong talks to us about battling Elon Musk in Quake in the ‘90s, his undefeated record as a pro gamer, and using AI to detoxify gaming.

Meg LeFauve and Dave Holstein drew inspiration from psychologists as well as their own children, becoming more understanding parents in the process.

Quibi was so focused on foresight they forgot the basics of hindsight.

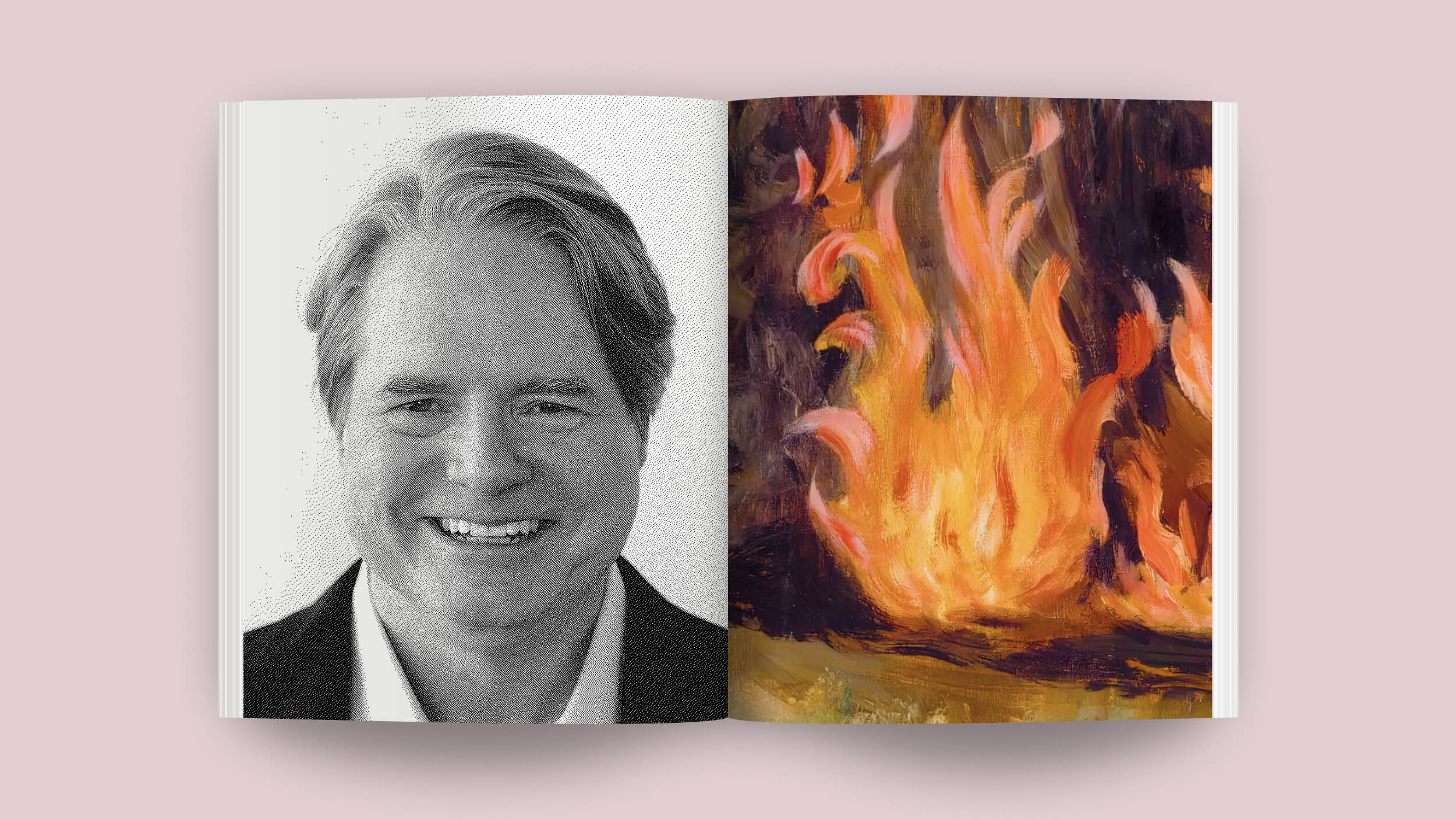

The rise and fall of Josh Harris — the genius who anticipated the digital revolution just a little too soon.

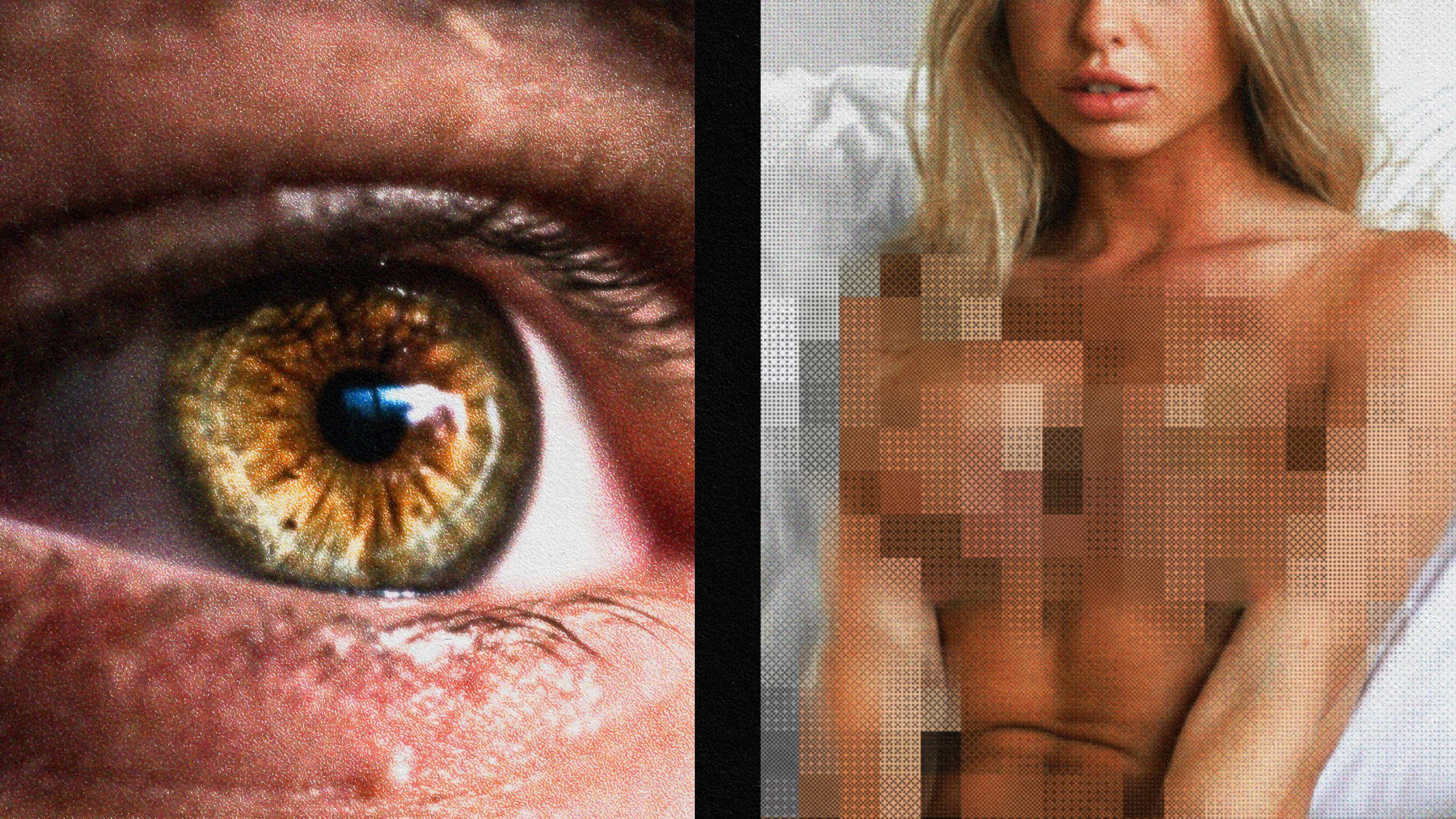

Everyone has to learn about sex somehow. Today, billions of people are learning about it from porn.

What you can learn about media by parodying it from the print era into the digital age.

Have you ever noticed how many things you interact with but can’t name? So did we.

Ryan Condal, who worked in pharmaceutical advertising before Hollywood, talks with Big Think about imposter syndrome, “precrastination,” and Westeros lore.

For most of human history, babies probably picked up language by overhearing.

In “Moral Ambition,” Dutch historian Rutger Bregman argues that all would benefit from a collective redefinition of success.

Concerns about privacy and pressures regarding the physical appearance of women and their homes contributed to the failure of AT&T’s 1960s Picturephone.

Each year, over half a million migrants cross the deadly jungle separating Colombia from Panama in search of a better life in the United States.

Rhetorical mastery is within everyone’s reach — equipped with some basic techniques you can rock it like Aristotle.

Should social media platforms have the right to decide what speech to allow online? Should the government?

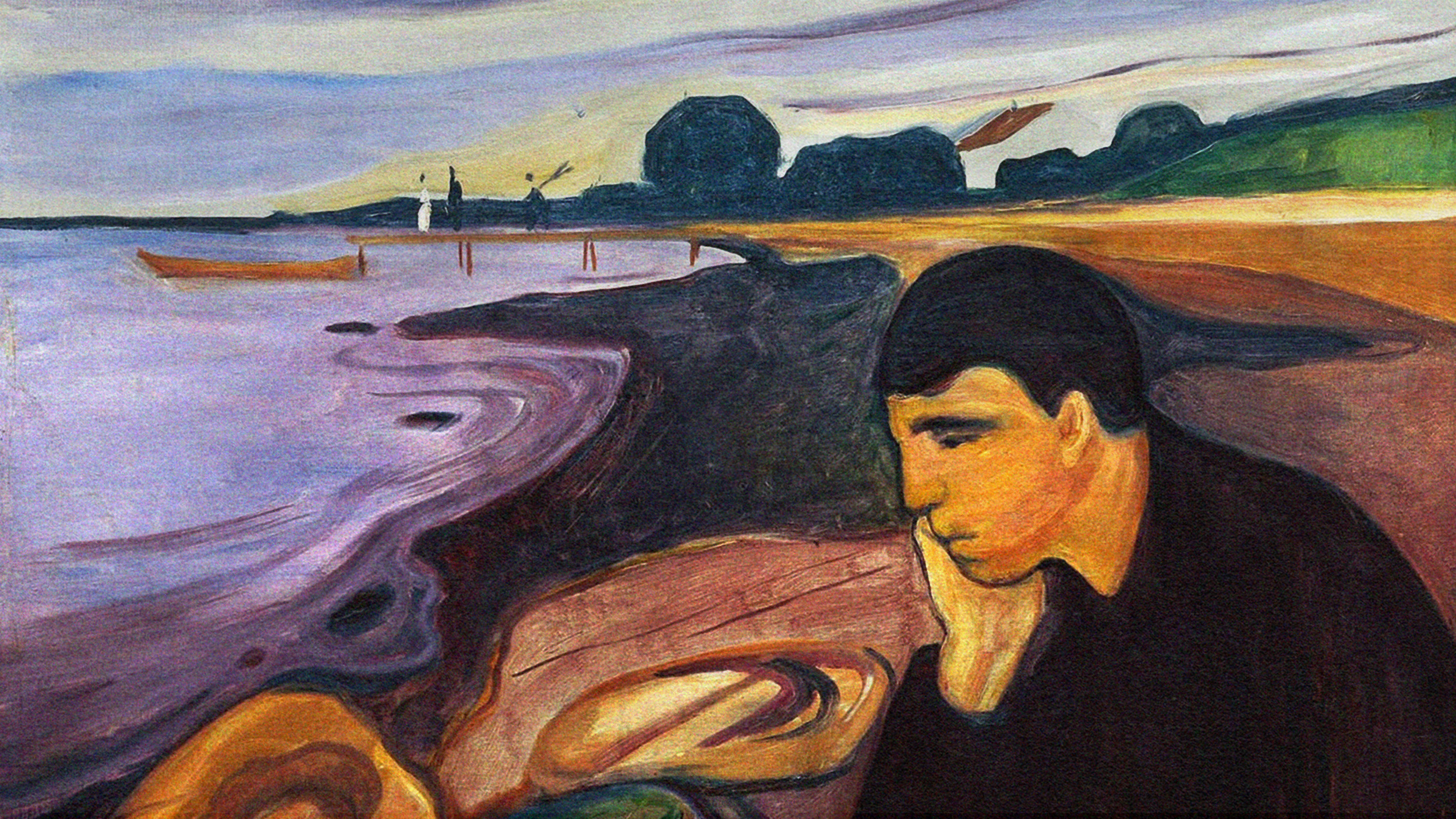

While weltschmerz — literally “world-pain” — may be unpleasant, it can also spur us to change things for the better.

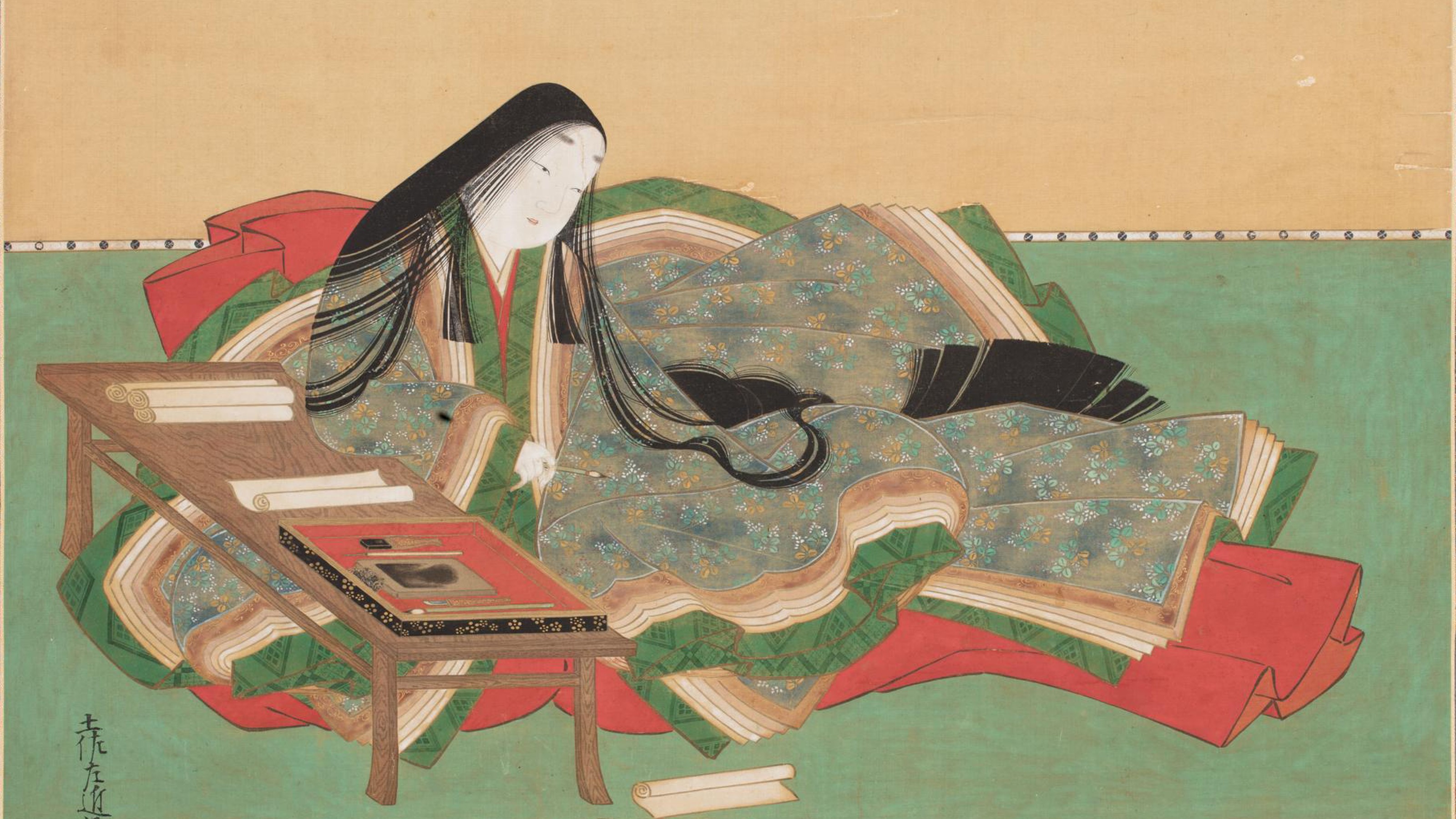

From Nick Carraway to Charles Marlow, these side characters offered truths their scene-stealing protagonists couldn’t.

Freethink asks three different kinds of experts to answer this question.

Acclaimed writer Mauro Javier Cárdenas used AI in his latest work to surprising effect.