- Researchers find that russet sparrows are among the many animals that self-medicate.

- It’s not clear whether this pervasive capability is learned behavior or instinctive.

- It’s likely animals have discovered some remedies we don’t yet know about.

This week, researchers from China published a study in which an intriguing behavior of russet swallows was described. The birds apparently administer what amounts to preventative medicine to their offspring: wormwood that kills parasites and promotes growth. This suggests two things: that they understand the beneficial properties of the plant, and that they are aware of and invest in their chicks’ future.

Remarkable as this may seem, the sparrows are just the latest addition to an already long list of animals that self-medicate, a capability that raises big questions. Is this behavior learned or is it instinctual? Is the knowledge shared among animal communities and families? Do animals try out different substances until they feel better? Does illness simply induce a physical taste for beneficial plants? Has natural selection favored the survival of animals who just happen to ingest medicinal substances?

The field of study that looks at animals who self-medicate is called zoopharmacognosy. “I believe every species alive today is self-medicating in one way or another,” Michael Huffman of the Primate Research Institute at Kyoto University told the New York Times in 2017. “It’s just a fact of life.”

Credit: karenkh/Adobe Stock

In that New York Times article, Huffman tells the story of a chimp he observed named Chausiku who treated a malaise by chewing the juice from the Vernonia amygdalina plant. According to a local ranger, the plant contains potent medicine but is also deadly at larger doses. Chausiku somehow knew just how much juice to ingest, and she recovered her energy in a few days. She recovered with a powerful appetite, suggesting the resolution of some manner of intestinal distress. Subsequent testing of the plant revealed it has multiple compounds with strong anti-parasitic qualities.

It seems clear that this sort of medicinal savvy is widespread throughout the animal kingdom. A PNAS article was shared by the National Center for Biotechnology Information in 2014. It noted, among other examples:

- Reports of bears, deer, and elk consuming medical plants.

- Elephants in Kenya that induce delivery of their calves by eating certain leaves.

- Lizards that eat a particular anti-venom root when bit by a snake.

- Red and green macaws that ingest clay that calms their digestion (dirt antacids!) and kills bacteria.

- Female wooly spider monkeys in Brazil whose fertility is enhanced by eating certain plants.

It may be primates who are most adept at self-medicating. Chimpanzees, bonobos, and gorillas are often seen swallowing rough leaves that clear their digestive tracts of parasites. Chimps with roundworms will also eat terrible-tasting plants that cure such infestations.

Numerous animals—such as the sparrows noted earlier and certain caterpillars—eat plants that kill or repel parasites.

Those russet sparrows aren’t the only ones who seem to be planning head, either. There are ants that use antibacterial spruce-tree resin to keep their nests germ free. Finches and sparrow line their nests with cigarette butts that keep mites under control.

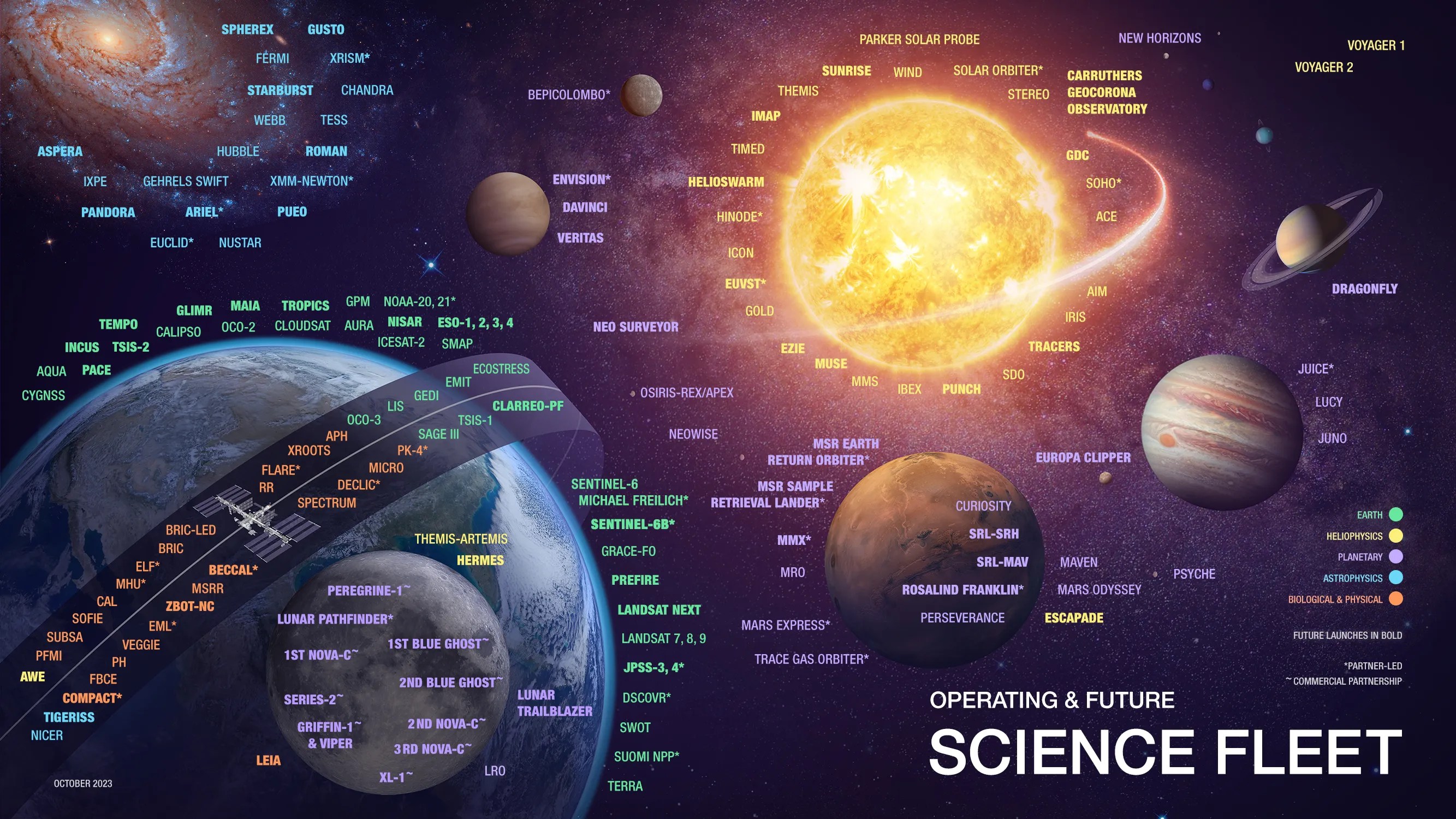

Credit: Thaut Images/Adobe Stock

If science is the practice of making observations, particularly of cause and effect, it may be that these animals are practicing a science of their own. As psychologist Robin Dunbar tell the Times, this method is simply how people and other living beings work out the way things work: “Science is a genuine universal, characteristic of all advanced life-forms.”

An animal’s source of medical knowledge may be as simple as that which comes to an individual with digestive issues who just happens to eat a plant that makes them feel better, a bit of knowledge that will come in handy when it once again gets sick. Perhaps others nearby see what’s happened and learn the trick to recovering from a stomach ache themselves. Perhaps offspring learn the medicine by observing their adults. Emory University’s Jaap de Roode, speaking with NPR, says that “primates are not so different from us. They can learn from each other and they can make associations between … taking medicinal plants and feeling better.”

On the other hand, it could also be natural selection at work. An animal with a natural inclination toward this kind of plant may ingest it when its tummy hurts. It then survives to reproduce while other individuals with tummy aches don’t. The animal uses the plant medicinally without any particular knowledge or understanding.

“People used to believe that you had to be very smart to [self-medicate],” says de Roode, but this may not be so. He cites the example of parasite-infected monarch butterflies who will lay their eggs in anti-parasitic milkweed, given the option. “I wouldn’t say it’s a conscious choice, but it’s a choice,” he says, since healthy monarchs don’t exhibit such a preference.

However this works, experts say we would be wise to keep an eye on all these non-human practitioners — there may be cures they know about that human physicians haven’t yet caught onto. As de Roode says, animals “have been studying medicine much longer than we have.”