#11: Allow Infant Euthanasia

When children are born with severe, debilitating conditions like some forms of spina bifida—in which some vertebrae on top of the spinal cord remain unfused and open—their lives can often amount to little more than a few months of extended agony. If they do survive, they usually need multiple operations, and often live out their lives with severe physical limitations.

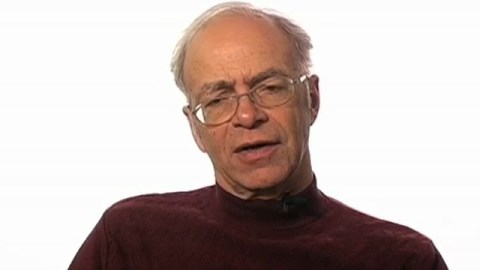

In some cases, says Princeton bioethics professor Peter Singer, when a physician describes what their child’s condition entails, parents come to the conclusion that it would be better for their child not to live. This is why he thinks that we should allow parents to decide whether to euthanize these severely disabled children.

Singer says he was presented with the issue by doctors in Australia who were, at the instructions of parents, not treating sick children—allowing them to slowly die from their conditions, usually before they were six months old. Singer says he and his colleague decided it is a “reasonable decision for the parents and doctors to make that it was better that infants with … the more severe variance of this condition should not live. … But we couldn’t defend the idea that the right thing to do then was to let them die. This seems slow and painful and … terribly emotionally draining on their parents and others.”

“The difficult decision is whether you want this infant to live or not,” says Singer. “That should be a decision for the parents and doctors to make on the basis of the fullest possible information about what the condition is. But once you’ve made that decision, it should be permissible to make sure that baby dies swiftly and humanely.”

In a 2005 op-ed in the Los Angeles Times, Singer looked at cases of such infant euthanasia in the Netherlands, where doctors were not prosecuted. He suggested that if we believe euthanasia should be allowed for infants who require a respirator to live, then we should also allow parents to euthanize children with conditions that have “‘hopeless prognosis’ and who also are victims of ‘unbearable suffering.'”

In addition to spina bifida, Singer told Big Think in an email that he thinks that there are many other conditions in which such euthanasia is defensible, if the family wishes it. “I would include severe cases of epidermolysis bullosa, Lesch-Nyhan sydrome, babies born without an intestine, trisomy 13 and trisomy 18,” he says. “And in a family unwilling or unable to care for a developmentally disabled child, and when there are no other families wishing to adopt such a child, I would include Down’s syndrome.”

Singer says there’s no absolute cut-off line in deciding which conditions should warrant this and which should not. “It depends on the family’s wishes,” he says. “Some families may be equipped, emotionally and financially, to cope with a severely disabled child, and others may not be, or may not want to have such a child. The final decision should be that of the family.”

Why We Should Reject This

Eva Kittay, a professor of philosophy at Stony Brook University says in an email to Big Think that she is “appalled to think that parents, in most cases supported by their physicians, allowed [children with spina bifida] to die—slowly or swiftly.”

A severely disabled infant is not necessarily near death, writes Kittay. “The parent comes to parent such a child with all the bias of the abled,” she says. “If the parent is not given the opportunity to fall in love with their child, as we fell in love with our daughter who has severe intellectual disabilities, cerebral palsy and seizure disorder, then there is not yet a heart warm enough to endure the cold words of the physician: this child is will live ‘a severely disabled life,’ ‘a life with a very low quality.’ And to the question, should this infant die a ‘natural’ but slow and agonizing death, or a swift and humane death, the latter response has a real appeal. But have these parent had the chance to embrace this child as their beloved child? Have they had the opportunity to inform themselves not just of ‘the cold facts’ but of the lived possibilities of a good life that this form of disability still presents? A swift decision to euthanize provides no emotional or temporal space for the attachment to grow, for the education to begin.”

Kittay notes that there have been dramatic advances in recent years in extending the lives of people with disabilities of all sorts. “Rather than rid our society, quickly and ‘humanely’ of severely disabled infants who are a ‘drain’ on resources, we ought to open ourselves up to the possibilities presented by disabilities, possible forms of cognition or perception that elude us when we all we have are our ‘normal’ intact capacities.”

While Kittay allows that a swift and painless death might be a better option for a particular infant suffering from a condition that involves a life of unremitting pain—where there is also no family willing to take the challenges the child presents—she still thinks finding a cut-off line is dubious: “Given the enduring biases within the medical profession, as well as the general public, this is an option that should, at best, be used in very rare circumstances, and is not warranted just because there is a severe disability in question. At the same time, we as a society, need to come to understand and develop rich forms of support and inclusion for disabilities of all different degrees.”

More Resources

— The Spina Bifida Association

— 2005 Los Angeles Times op-ed by Peter Singer: “Pulling Back the Curtain on the Mercy of Killing Newborns“