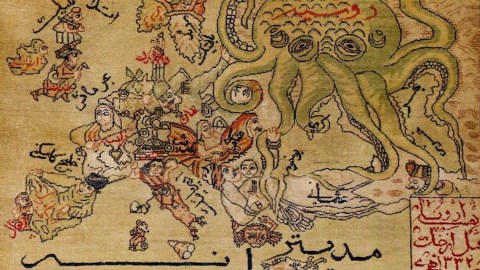

A Crowd-sourced Translation for a Mysterious Map Rug

This rug would really tie any map-lover’s room together. It is the product of two venerable map-making traditions, one eastern, the other western.

Since at least the time of the Soviet occupation (1979-’89), Afghanistan is the source of so-called ‘war rugs’: carpets depicting the instruments of modern warfare rather than ancient geometric patterns (see #395).

This particular rug fits into that tradition – except that it appears to be much, much older. The image it copies is one of the iterations of the famous ‘serio-comic’ maps that were popularised by Fred W. Rose and translated across Europe in the decades preceding World War I (See #521).

These maps showed animate versions of European nations, variously trampling, shoving and strangling each other. This rug is an almost identical copy of the Fred W. Rose map. Its main feature is Russia as an octopus, stretching out its tentacles towards Central Europe, the Balkans and the Middle East.

Spain and Portugal are recognisably cast in the same awkward position across the Iberian peninsula. France is represented by a female form rather than the moustachioed gentleman in the Rose map, but this version of Marianne seems to be wearing a Muslim headscarf rather than a Phrygian cap. The maiden representing the Austro-Hungarian Empire is no longer bare-chested, and also more modestly dressed.

This map appeared here on Reddit‘s Mapporn section, without further indication of source or context. Who can offer a translation for the words on the rug in Arabic script – and/or offer an indication of its provenance, age and motivation?

UPDATE (16 December 2017) – Below some more information on the content of the map/rug. Thanks all contributors!

Tom R., of Iranian descent, says the writing on the map is Persian as used before the 1950s, and suspects the map dates from 1920s Iran. “The writing in the box at the bottom corner says: Map of Europe before the war of 1914. (=1322 in the Islamic lunar calendar)”. Some other observations by Tom:

- “Although there are at least two words in Arabic on the map (بحر = sea and سنه = year) rather than their Persian equivalents (دریا and سال), I’m 100% sure the language is Persian. A large number of Arabic words were used regularly in Persian, and many still are. These two words are among those that were replaced in both spoken and written Persian by an Academy appointed by Reza Shah”. Reza Shah Pahlavi was the Shah of Iran from 1925 to 1941.

- “Two specific points that prove the language is not Arabic. One is the word نقشه (map) in the box, which is not Arabic. Second, and this can be missed easily: the Persian word for ‘Norway’ comes from its french pronunciation as نروژ which has as its last letter ژ which is one of four letters that do not exist in Arabic”.

- “I think the source for this map was another one than the one you’ve put in the post, because aside from the changes in the figures that you pointed out, the writings are not exactly equivalent either. For example: the carpet specifies the body of water between France and Britain as the ‘Sea of Manche’”. The English Channel is called ‘La Manche’ in French – pointing to a French version of this map as the probable source for this one.

Jordan Toy concurs that the writing is in Persian, adding that “it looks like water features are in black and countries are in red”. Some translations:

- “Between France and Spain, you have Bay of Biscay (خلیج بیسکی), which looks just like it on the rug”.

- “The octopus is Russia (روسیه), which you can see in red text”.

- “The Baltic Sea is shown as بالتیک, the Adriatic Sea is shown tilted (almost upside down) as آدریاتیک”.

- “Germany is shown as آلمان”.

- “The big black script on the bottom (مدیترانه ای) means the Mediterranean”.

Philippe L. also tried his hand at translating the main elements of the map, and produced this annotated version.

He agrees that the map is in Farsi (Persian), and offers the following observations:

- “Most of the names are translations of the countries or seas. There are some capitals (London, for instance and not England)”.

- “The name for the Mediterranean derives from ‘mediterranean’, whereas in Egyptian Arabic it would be called the ‘White Sea’”.

- “The label for Caspian Sea, the first word (بحر = bahr) means sea, while the second word looks like “خزر” (khazar). According to Arabic wikipedia, this was its name in the Middle Ages. And according to English wikipedia, it’s its Turkish name as well”.

- “Spain is labelled by the name of its inhabitants (‘Spanish’) rather than the country name”.

- “Austria is written as ‘Autrich’, after the French version of the country name (Autriche), while in Arabic its name is ‘Nemsa’ – derived from Russian”.

Got more? Send your input to: strangemaps@gmail.com.

Strange Maps #874