What the world will look like 4°C warmer

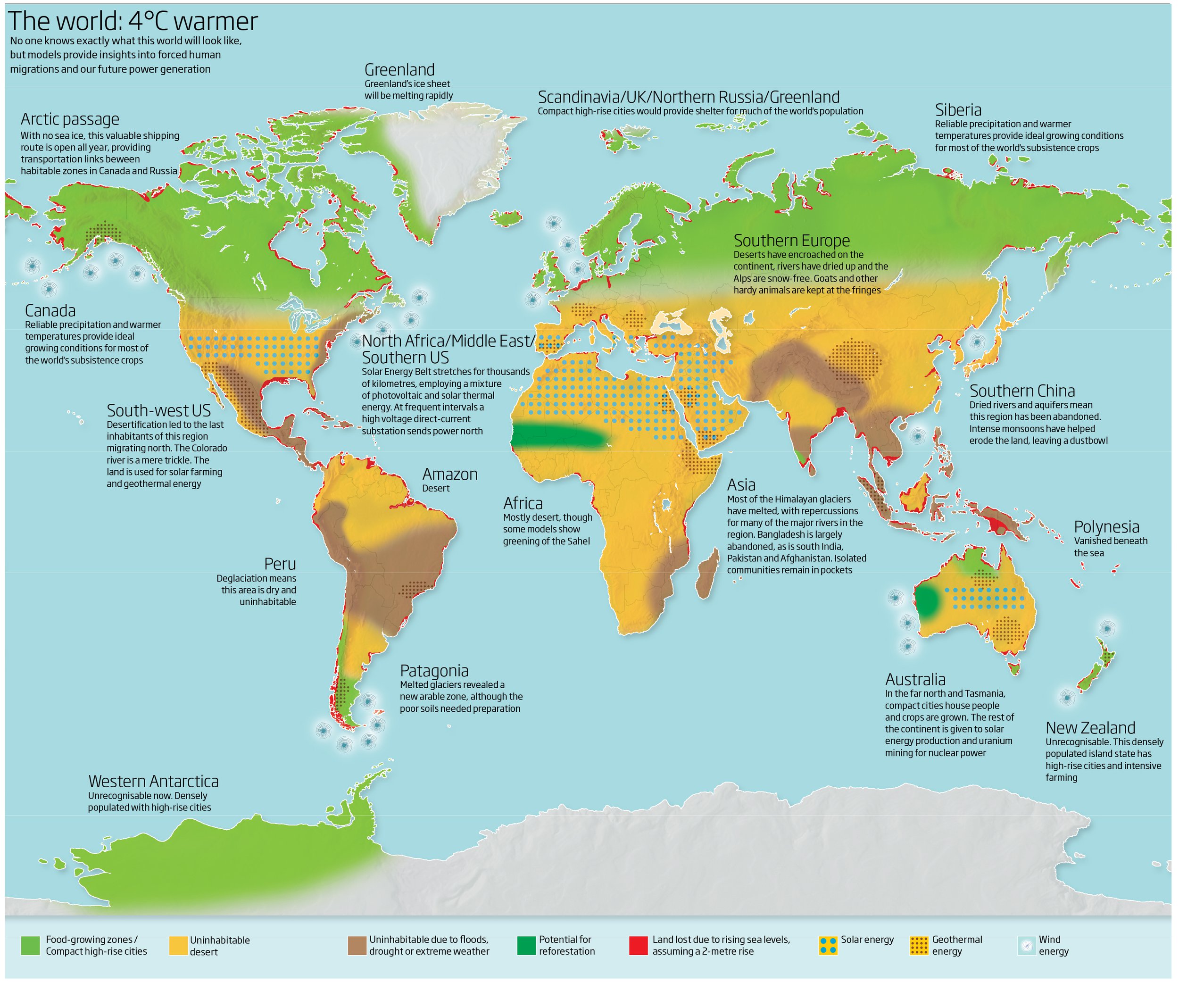

Micronesia is gone – sunk beneath the waves. Pakistan and South India have been abandoned. And Europe is slowly turning into a desert. This is the world, 4°C warmer than it is now.

But there is also good news: Western Antarctica is no longer icy and uninhabitable. Smart cities thrive in newly green and pleasant lands. And Northern Canada, Scandinavia and Siberia produce bountiful harvests to feed the hundreds of millions of climate refugees who now call those regions home.

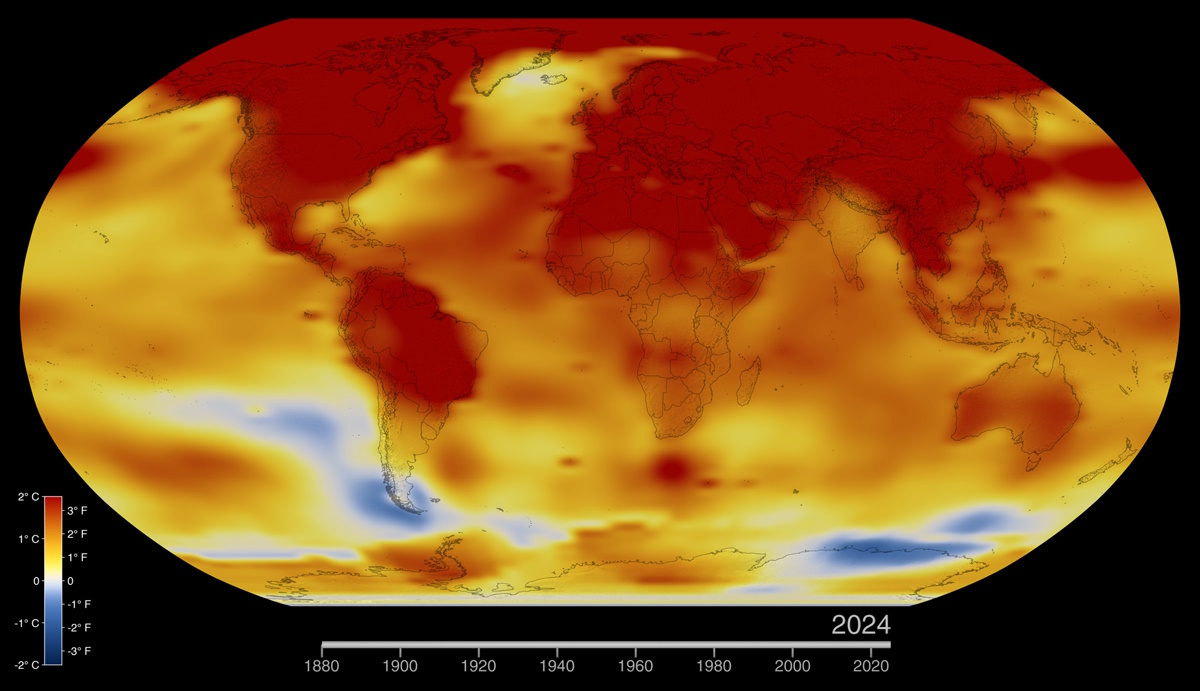

This map, which shows some of the effects a 4°C rise in average temperature could have on the planet, is eight years old, but it seems to get more contemporary as it ages (and the planet warms). Antarctica is white with snow and ice, on the ground and, traditionally, on most maps. This map has turned the continent’s western end incongruously green. And recent reports confirm that Antarctica is indeed turning green.

Few serious scientists doubt that climate change is happening, or that it is man-made. But the fact remains that many still have a hard time grasping global warming, partly as a convenient way of ignoring the destructive impact it is predicted to have.

Those on the fact-based side of this argument should realise that continuously bombarding the opposition with doom and gloom is likely to reinforce their resistance to accepting the new paradigm.

This map offers an alternative: lots of misery and disaster, but also plenty of hope and solutions. Not solutions that will lead us back to the climate of a few decades ago – costly and pointless – but solutions that work for the world as it will be, when it will be much warmer than it is now.

First, the bad news. Brown indicates ‘Uninhabitable due to floods, drought or extreme weather’. Say goodbye to the Eastern Seaboard of the U.S., to Mexico and Central America, to the middle third of South America. In Africa, Mozambique and Madagascar are gone; Asia loses much of the Indian subcontinent, including all of Pakistan; Indochina is abandoned, as is most of Indonesia. As the map mentions, “The last inhabitants of (the South-west U.S. are) migrating north. The Colorado river is a mere trickle”; “Deglaciation means (Peru) is dry and uninhabitable”; and “Bangladesh is largely abandoned, as is South India. (In) Pakistan, isolated communities remain in pockets”.

Orange is not much better: ‘Uninhabitable desert’. That’s most of the U.S. and the rest of South America, almost the entirety of Africa and the southern halves of Europe and Asia. “Deserts have encroached on (Southern Europe), rivers have dried up and the Alps are now snow-free. Goats and other hardy animals are kept at the fringes”, the map predicts.

Red is for lands lost to the rising tide (assuming +4°C adds two metres to ocean levels). This may not seem a lot, but this is where populations are concentrated. In the U.S. for instance, counties directly on the shoreline constitute less than 10% of the total land area (not including Alaska), but account for 40% of the total population.

But there is a flipside. Light-green stands for food-growing zones, and compact high-rise cities. That’s Western Antarctica, “unrecognisable now. Densely populated with high-rise cities”. New Zealand, sparsely populated in our time, will also be transformed into a high-density population centre. There will be a lot more room for this in the northern hemisphere: Siberia and Canada, where “reliable precipitation and warmer temperatures provide ideal growing conditions for most of the world’s subsistence crops.” And the UK, Scandinavia, Greenland and northern Russia, which will be dotted with compact high-rise cities to “provide shelter for much of the world’s population”.

A warmer climate could even lead to reforestation in certain areas of the world, including the Sahel and Western Australia. The regions abandoned to desertification are empty, but not useless: they will be used for solar farming (green dots) and geothermal energy (red dots). Giant wind farms off the coasts of South America, Alaska and in the North Sea will generate the remainder of the planet’s energy needs.

This map was first published by New Scientist and republished by Parag Khanna for his book Connectography. Khanna speculates: “The entire population of the Arctic region today is less than 4 million. Could it be 400 million within the coming 20 years?”

Now is the time to buy property in Greenland – before it too turns green…

Strange Maps #842

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.