How the Yazoo Land Scandal changed American history

Credit: New Georgia Encyclopedia via public domain

- Few people today are familiar with the Yazoo Land Scandal, which broke in the mid-1790s.

- Yet it sent shockwaves through American public life, influencing politics, law, and even geography.

- Without it, Georgia could have been a “super state” — and the Trail of Tears might not have happened.

There are no good old days.

Travel back, say, to the presidency of George Washington himself. Yes, the father of the nation, he who could tell no lie. Even under POTUS #1, there was corruption so venal and egregious that it changed the very map of America. In other words, without the Yazoo Land Scandal, the political geography of the United States might have looked quite different. Yet despite its catchy name and far-reaching consequences, few now remember the affair.

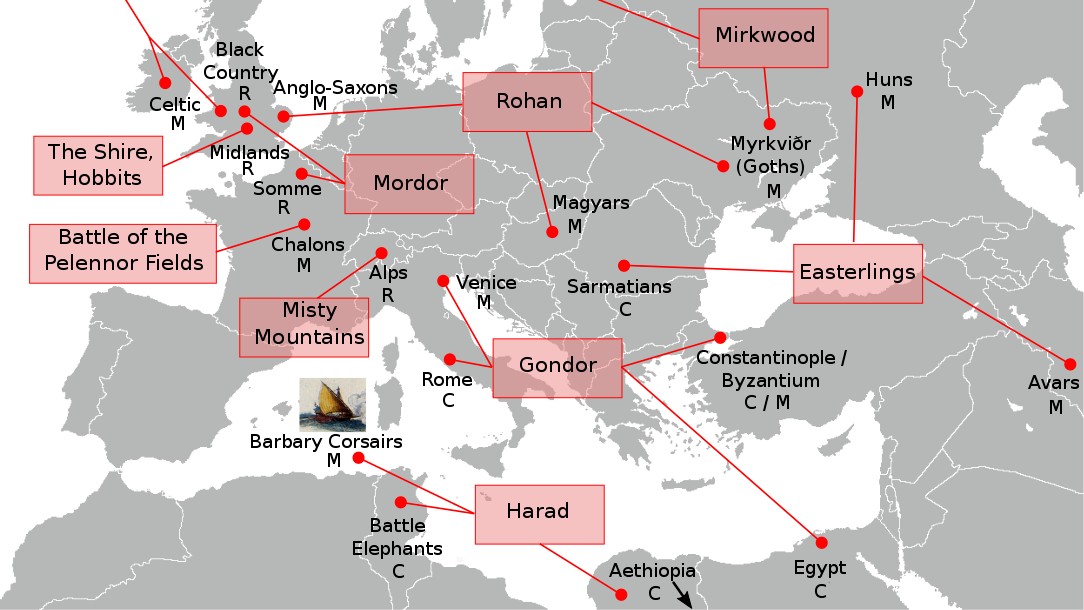

The scandal centered on Georgia, the last holdout in the process of state cessions. Of the original 13 colonies-turned-states, seven had entered into the Union with vague, contested, and often overlapping land claims, mainly in the region between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River.

The six states without claims did not want to be overshadowed by their expanding neighbors. And the federal government did not want them to get into fights where their claims overlapped. So the U.S. government spent its first few years convincing and cajoling those seven states to abandon their claims. When New York relinquished its claim to Vermont in 1790 (for a mere $30,000), that process was complete. With one exception.

Yazoo Land Fraud

Georgia continued to claim territory all the way to the Mississippi River. For various reasons, the state was loath to give up its interest in these so-called Yazoo Lands, corresponding to the larger part of the present-day states of Mississippi and Alabama. Not least because of money. Land developers were eager to acquire large chunks of the country, their guiding principle being: bribe high, pay low.

In 1794, four companies, set up especially for the purpose, paid half a million dollars for about 40 million acres of land. Even taking into account all the bribes — another half a million — that was a ridiculously low amount: four acres to a dollar.

Infuriated by the deal, Georgians booted out the legislators who had their palms greased to approve the Yazoo Act, by which Georgia had sold all that land on the cheap. In 1795, a new state legislature voted a Rescinding Act, overturning the sale. All extant copies of the original Act were collected and burned at high noon on the grounds of the state capitol under construction, then in Louisville. (One copy escaped destruction — the one sent to President Washington).

The Yazoo hits the fan

But that was far from the end of the unpleasantries. In fact, this is where the actual scandal started. For the land companies did not admit defeat. They continued printing bonds that were being traded and sold on the financial markets of New York, Boston, and Philadelphia, raking in tidy profits.

Thousands of bond buyers acquired a stake in the Yazoo Lands. Eventually, though, the market smelled a rat. Investors started to worry: had they thrown away their money on a fraudulent land scheme?

Georgia paid back some of the duped buyers, but unable to handle the escalating scale of the scandal, the state eventually did surrender its claims to the Yazoo Lands to the federal government. Under the so-called Compact of 1802, the U.S. paid Georgia $1.25 million, took over any remaining liability for the Yazoo Lands, and promised to rid Georgia of any remaining Native American land claims.

So, the duped investors could now sue the federal government instead of Georgia. The land companies, for their part, wanted the U.S. to uphold their claims, which they continued to consider legal and valid. Who was right?

In 1810, the case reached the highest court in the land. Pronouncing on Fletcher v. Peck, the Supreme Court ruled that the Rescinding Act was unconstitutional and the original land deals remained legal. For although those deals were corrupt and not in the best interest of Georgians, the contracts were made by the Georgia legislature, which had the authority to do so. The Supreme Court ordered the U.S. government to pay out $4.5 million in compensation to the claimants.

Yazoo changed the course of American history

Fletcher v. Peck was a landmark case in more ways than one. For the first time ever, the Supreme Court had ruled against a state law, that is, Georgia’s Rescinding Act. This established the principle that federal laws were supreme over state laws. The case also firmly established that a legal contract could not be nullified by a later law, which became an important principle in contract law.

The Yazoo Land Scandal had two further, major consequences for the United States. Without the scandal, Georgia might conceivably have managed to hold on to its western lands. This hypothetical Greater Georgia, running from the Atlantic to the Mississippi, would have comprised most or all of the current states of Mississippi and Alabama. That would make it one of America’s most populous states, its 20 million inhabitants on par with Florida and New York and surpassed only by Texas (30 million) and California (40 million).

Georgia could also have avoided one of the most ignominious events in its history. In 1830, the federal government fulfilled its promise in the Compact of 1802 to rid Georgia of all extant Native American land claims by the Indian Removal Act. Signed into law by President Andrew Jackson, the Act led to the “Trail of Tears,” the forcible removal of the Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Seminole, and Chickasaw tribes — about 100,000 people in all — to reservations west of the Mississippi, in what would later become Oklahoma.

Although now largely forgotten, the Yazoo Land Scandal helped shape the territory, laws, and institutions of the early United States. But the affair has another lesson for our times. If there are no good old days, then our current ones perhaps aren’t so bad either.

Strange Maps #1079

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].