576 – Baltic Ifs and Polish Buts

Maybe it’s because the country’s shape tends towards a square, but Poland’s borders give it a solid, anchored appearance on the map of Europe. And yet those borders are relatively new; few other countries, if any, have expanded, contracted and generally moved around on the map quite as erratically as Poland.

Poland’s cartographic odyssey serves as a yardstick to the highs and lows of the nation: at one point, a Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth controlled an empire stretching from the Baltic to the Black Sea. On several other occasions, Poland was carved up by its Prussian, Russian and Austro-Hungarian neighbours, and completely disappeared off the map.

This extreme variation makes Polish history an exceptionally fertile subject for allohistorical speculation: if our present timeline is the result of relatively random choices at particular forks along the march of time, what would have happened had other paths been followed? In any scenario, the options are as innumerable as in the many-worlds theory, of course, but Polish history perhaps has a few more concrete starting points.

One of these starting is the extremely fluid situation after the First World War, when Germany’s defeat and Soviet Russia’s weakness created a power vacuum in Eastern Europe, allowing for Poland and the Baltic states to re-establish themselves after an extended period of Russian imperial domination – and fight about where the borders between them should be. This map is a snapshot of that situation, and shows a political arrangement that existed for a very brief period only.

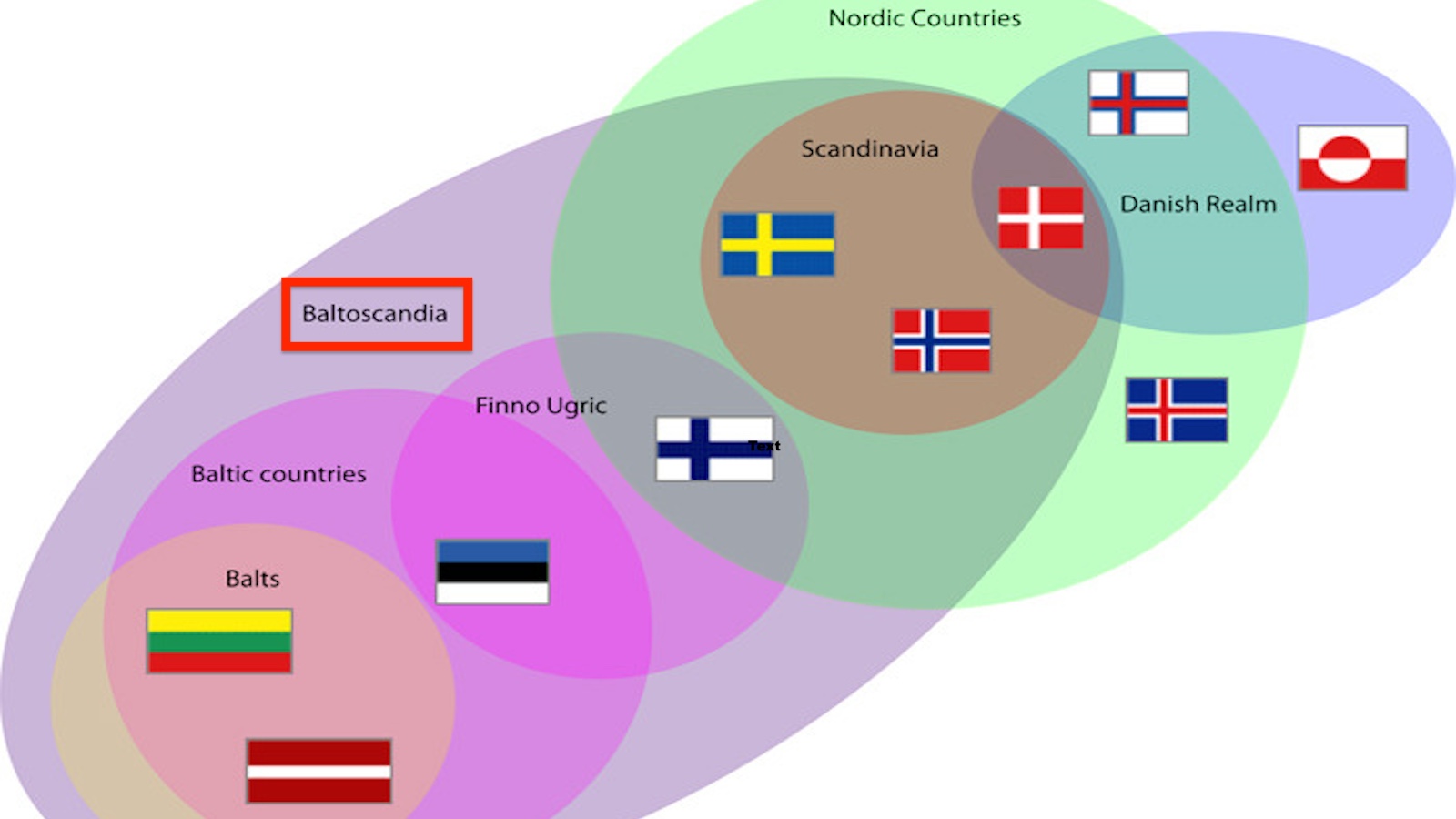

Let’s start with the Baltic situation. We’re used to there being three Baltic states – or none, when they were gobbled up by the Russian/Soviet empire – but on this map, there are two. Or four, depending on how you count. The northern Baltic entity is divided in three: Esthonia (only covering the northern part of present-day Estonia), Livonia (spanning the south of present-day Estonia and a large part of Latvia) and Kurland (the southern part of today’s Latvia).

The other (or fourth) Baltic state is Lithuania, but remarkably smaller than it is today. The state is denied sea access by the territory of Memel, detached from Germany after the war by the League of Nations. On the other side, it misses a great chunk of its present eastern territory.

In turn, East Prussia is cut off from the German ‘mainland’ by the Polish Corridor, and by the Free City of Danzig. East Prussia itself is divided in two, with the southern half still an ‘area for plebiscite’ (which would have to determine whether the territory wanted to remain German or not).

A similar area is detached from eastern Silesia (note just east of that area’s border the small town of Auschwitz). Another, smaller area to the south is also detached, although it is not immediately apparent from which entity (Poland, Czechoslovakia or Silesia) and for what purpose.

Interestingly, the map also appears to show a Lithuanian enclave in Kurlandish territory, somewhere between Jakobstadt and Dvinsk (not to be confused with Minsk or Pinsk). Unfortunately, the enclave’s name is illegible.

The map still shows Vilnius (Wilno in Polish, Vilna on the map) as Lithuania’s capital; although it was the spiritual centre of Lithuanian nationalism, Lithuanian was heavily minoritary, the majority being Polish. After a Polish invasion and a period of detachment as the Central Lithuanian Republic (1920-1922), Vilnius and the surrounding areas were annexed by Poland. Kaunas – on this map rendered as Kovno, slightly to the west of Vilnius – was thereafter proclaimed Lithuania’s ‘provisional capital’.

In 1939, as compensation for losing its independence, Lithuania was gifted with Vilnius by the invading Red Army; the Soviet Union not only locked away the Baltic states until its collapse in 1991, but also shaped their borders – and that of Poland – as we still know them today. This map serves as a reminder that things could have turned out quite differently.

This map, taken from the 1920 edition of The People’s Atlas (London Geographical Institute), shows the still-fluid situation in the Baltic after the treaties of Versailles and Brest-Litovsk, but before the Peace of Riga. Found here on Wikipedia.