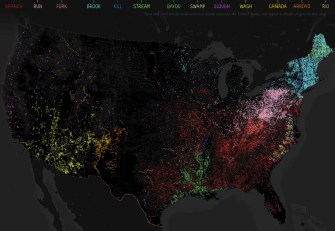

531 – A Rio Runs Through It: Naming the American Stream

A body of running water may be called any of many different names, the most generic being stream, the most common being river. A river can be defined as ‘a natural stream of water of usually considerable volume’. General terms for smaller streams include creek (smaller than a river) and brook (smaller than a creek). Very specific types of water currents include anabranches (river branches that rejoin the main body of water) and distributaries (branches that don’t).

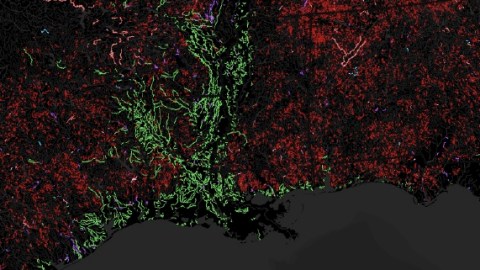

This map charts the rich variety of waterflow toponyms in the US, which reflects the climatological and geographical diversity of the country, but also its linguistic and historical heritage. River names seem extremely resistant to change, and indeed often are echoes of earlier dominant cultures [1].

The colours on the map, which is based on the place names in the USGS National Hydrography Dataset, correspond to the generic toponyms for waterflows, excluding the two commonest ones (river and creek, rendered in gray).

The term brook (light blue) is massively prevalent throughout New England, and into northern New Jersey and Pennsylvania. It is interspersed with stream (light green) in Maine, the only place in the country where that term is used with any frequency; and with kill (dark blue) in New York state’s Hudson valley – the occurrence of that Dutch-derived term coinciding somewhat with the former Dutch colony of New Netherland.

Pennsylvania, Maryland, northern Virginia, West Virginia and Ohio are dominated by the run (pink), while branch and fork (darker and lighter red respectively, and not easily distinguishable) dominate much of the South. One glaring exception is the lower Mississippi valley and the Gulf coast, centred on New Orleans, where the bayou (dark green) holds sway, reflecting French settlement.

Spanish heritage is reflected by certain generic names predominant in the southwest, i.e. rio (yellow), arroyo (dark orange) and cañada (light orange).

Other terms denote certain types of water, like the wash (yellowish green) in the Southwest, reflecting that water body’s periodic nature, the slough (purple) throughout California and the Northwest, often a tidal body of water, and the swamp (faded green) along the Atlantic coast, indicating the area where more or less stagnant bodies of water are likely to occur.

The map was produced by Derek Watkins (here on his blog about cartography, neogeography and genius loci in a networked world); in a very lively comments section, some interesting points raised about this map include:

Many thanks to Michael Hindley for pointing out this map, which, fascinating as it is, clearly only skims the surface of a subject with much, much deeper waters…

——

[1] The names of many European rivers are of Celtic, Indo-European, or even older origin. The Ukrainian rivers Dnieper and Dniester, for example, respectively mean ‘the far-away river’ and ‘the close-by river’ in Sarmatian, an Iranic language. Many American rivers carry Indian names. This historic resonance is one reason why rivers play such a prominent role in Finnegan’s Wake, James Joyce’s last work, arguably the world literature’s most extended pun.