343 – To which Viktor the Spoils? A Tale of Two Ukraines

Russia is no longer the hub of a worldwide Communist empire, nor the main ingredient of the Soviet Union; but the Kremlin still insists on wielding power in its old sphere of influence, an area of special interest to Russian foreign policy that it calls the Near Abroad.

The most recent – and, to Russia’s other neighbours, most intimidating – example of that insistence was this summer’s brief Russo-Georgian war, in which the Russian Army established final control over Georgia’s breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, eventually recognising their independence.

In the years immediately following the Soviet Union’s collapse, Russia was too weak to prevent what it qualifies as EU and NATO ‘encirclement’ (an old Russian geopolitical worry). But now, a resurgent Russia flush with oil money insists on checking what it sees as further encroachment by the EU and(especially) the US.

The term Near Abroad therefore excludes far-flung corners of the worldwide socialist experiment, such as Vietnam or Cuba (although Russia maintains good relations with old-school leftist regimes such as Cuba’s and new ones such as the Venezuela of Hugo Chavez).

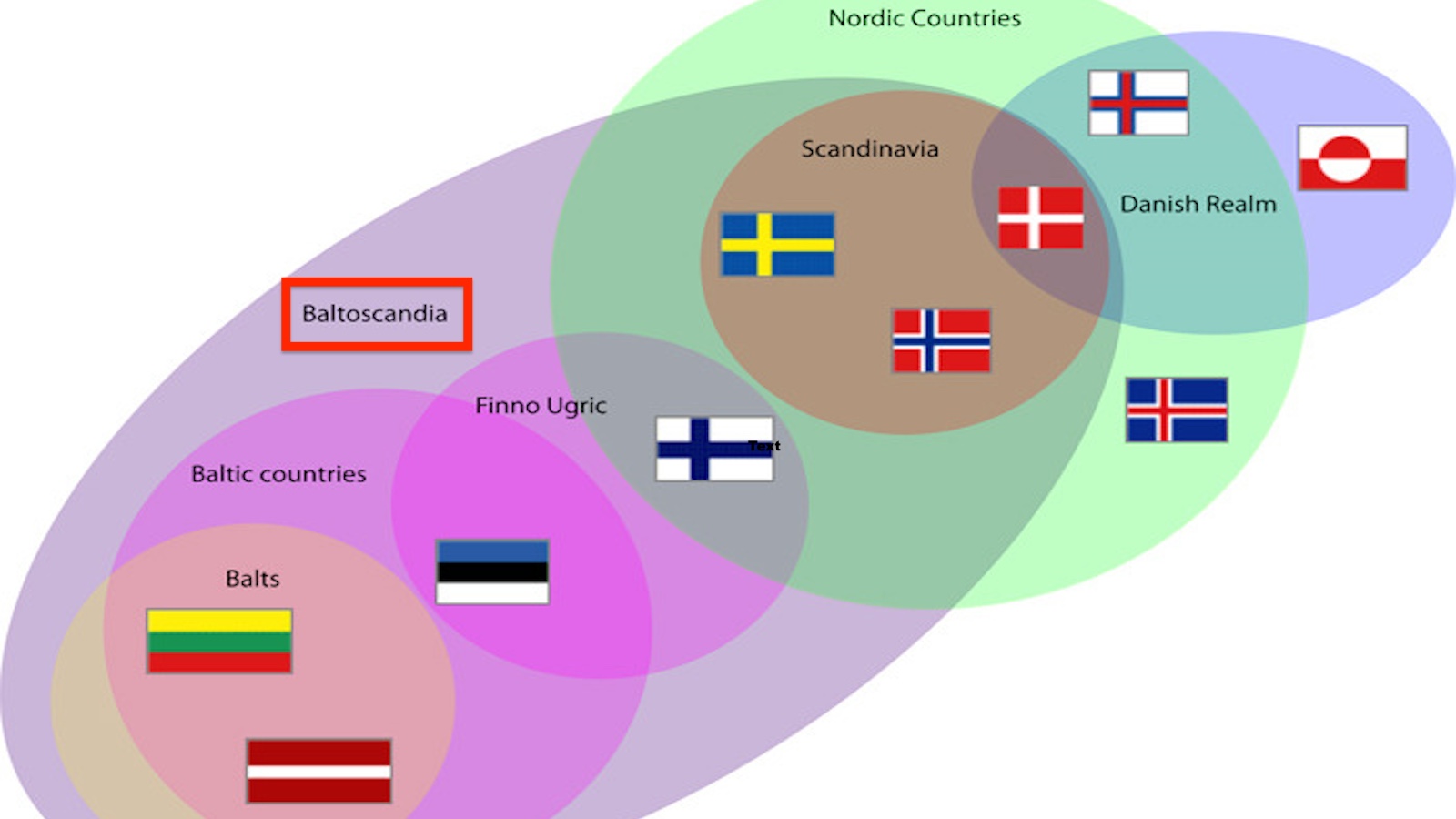

It also seems to exclude what used to be called Eastern Europe, states that were independent before 1945 and are again now, almost all firmly lodged in western institutions such as the European Union and NATO (i.e. East Germany, Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Rumania, Bulgaria; of the former Yugoslav states, only Slovenia is fully integrated).

An interesting twilight zone are the Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania), in NATO and the EU, but with considerable historical baggage vis-a-vis their giant neighbour to the east – they were independent between the World Wars, but part of the Soviet Union thereafter, and each harbours considerably large Russian minorities.

The Ukraine however, with 45 million inhabitants and about the size of France, is firmly within Russia’s Near Abroad. Its east is ethnically mainly Russian (Ukrainian nationalism tends to be a western thing), and Russia has strategic interests in the Crimea (Russian until 1954, when it was transferred to the Ukraine, but still home to Russia’s Black Sea Fleet). The country itself seems divided on whether it is an eastern outpost of the west, or a western outpost of the east.

The 2004 ‘Orange Revolution’, in which pro-western candidate Viktor Yushchenko successfully contested the rigged results of the presidential election that was ‘won’ by his pro-Russian opponent Viktor Yanukovich, seemed to place the Ukraine firmly in the western camp. Ukrainian politics has however seen several reversals of fortune since that time, proving that Ukraine is unique among the former Soviet republics: pro-western and pro-Russian sentiments are almost completely in balance.

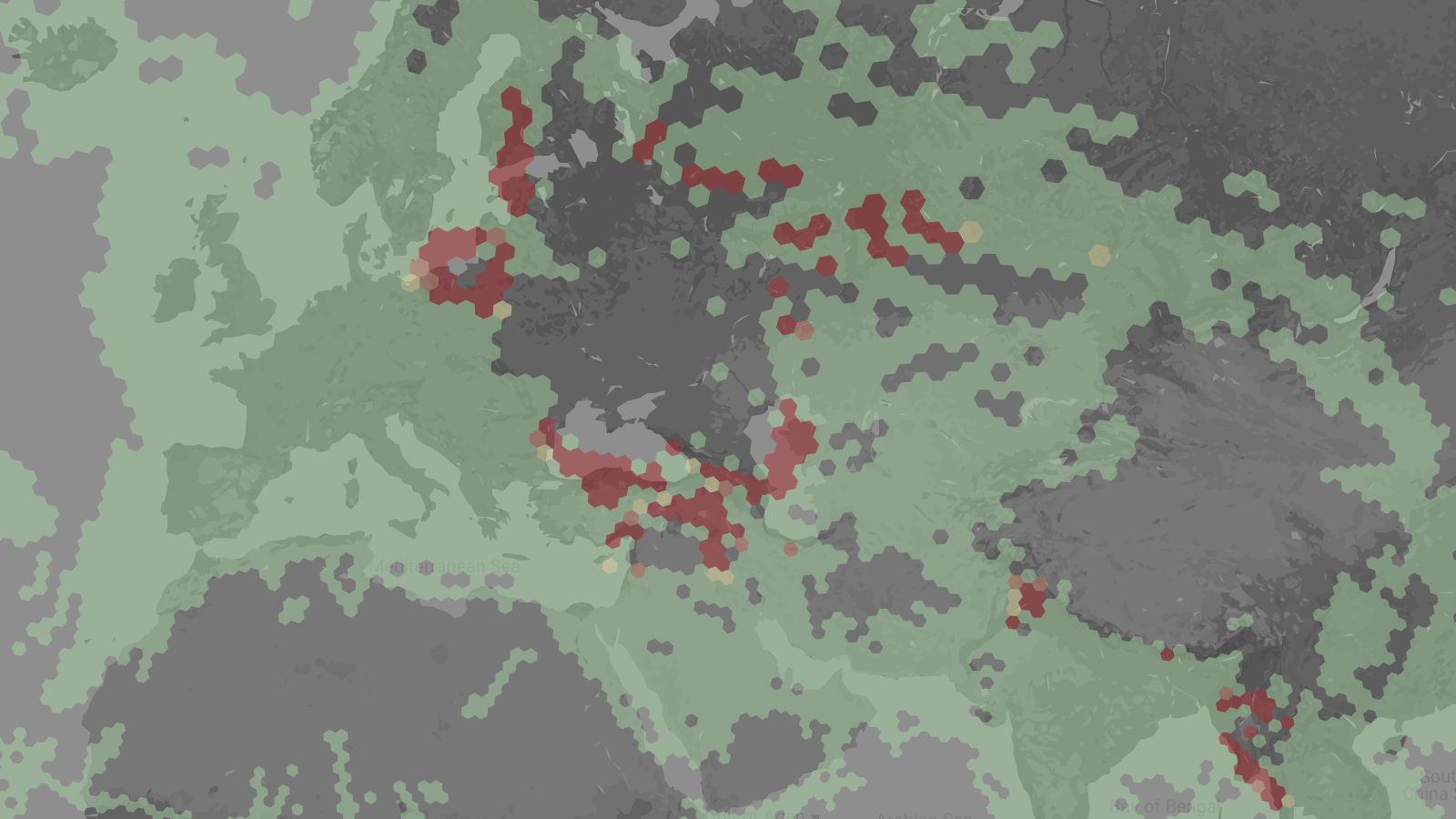

That balance is not spread out evenly across the country. This map shows which of both Viktors was the victor in each of Ukraine’s regions in the (contested) November 2004 presidential elections. Each candidate has won in a remarkably contiguous area – Yushchenko winning the northwestern half of the country, Yanukovich the southeastern part. Both Moscow and the West are eager to have the populous, and potentially prosperous Ukraine in their camp. Will the fault line running through the Ukraine become the front line of a Second Cold War?

This election map was taken here from Wikimedia Commons.