How Come East is West and West is East?

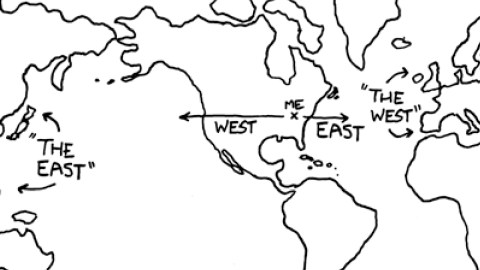

If you’re American, geographically inclined and a bit of a stickler, this cartographic incongruity is a bit of an annoyance. From the US, the shortest route to what’s conventionally called ‘the East’ is in fact via the west. Going in that direction, you’ll hit the ‘Far East’ before you’re in the ‘Middle East’. And Europe, or at least that part usually included in ‘the West’, lies due east. So East is west, and West is east, in blatant contradiction of what’s probably Rudyard Kipling’s most famous line of verse:

Oh, East is East and West is West, and never the twain shall meet

This opening line of The Ballad of East and West is often quoted to underline some insurmountable difference between the two hemispheres. It has almost invariably been misused. Taken as a whole, the Ballad has a subtler message than the one implied in this single verse. It attributes the gap between the two cultures more to nurture than nature. The entire couplet (which also closes the poem) reads:

Oh, East is East and West is West, and never the twain shall meet

Till Earth and Sky stand presently at God’s great Judgment Seat;

But there is neither East nor West, Border nor Breed nor Birth,

When two strong men stand face to face, tho’ they come from the ends of the earth!

The poem dates from 1889 and is set in the British Raj. At least here the context is pretty clear: Britain is the West, India the East. But definitions of ‘East’ and ‘West’ vary greatly throughout history – and remain fluid. To stick to the British perspective of the poem, where did (and where does) the East begin? The Berlin Wall? Istanbul? The Middle East? Persia? The Indus River? Or at the Greenwich Meridian, placing London in both the eastern and western hemispheres?

As it turns out, a general definition for what is East and where West is, one that transcends place and time, is impossible to formulate. This is because both terms are ambiguous to start with. The word West derives from an Proto-Indo-European root [*wes-] that signifies a downward movement, hence associated with the setting sun (cf. Latin vesper, from the same root and meaning both ‘evening’ and ‘West’). The Proto-Indo-European root for East is [*aus-], which has the opposite meaning, i.e. an upward movement (of the sun), dawn.

As those etymologies suggest, East and West are but a matter of perspective. East is where the sun rises, West where it sets – as viewed from wherever you are. Which, incidentally, also means that it’s essentially impossible to be ‘in’ the East or West, as both aren’t fixed places, but shift with the horizon.

Nevertheless, ‘East’ and ‘West’ have been embedded in our topographies ever since civilisations started naming the world around them. Take Europe for example. The name quite possibly derives from the Phoenician word ereb, meaning ‘setting’ (as in ‘setting sun’), as it lay to the west of Phoenicia (present-day Lebanon, more or less). Similarly, the term Maghreb, used to describe the North African region at the western edge of the Arab world (i.e. Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia), is Arab for ‘sunset’ or ‘western’, as that is indeed their position from a peninsularly Arab point of view.

Point of view is crucial, of course. East and West only exist in relation to someplace else. For many centuries, Europe was the vantage point from which the world was discovered, viewed and named. Columbus sailed west to arrive East in India, but instead stumbled on a new continent. It took a while for the confusion to lift, so the first name for America was the Indies, from 1555 on shifting to West Indies (when the mistake became increasingly apparent).

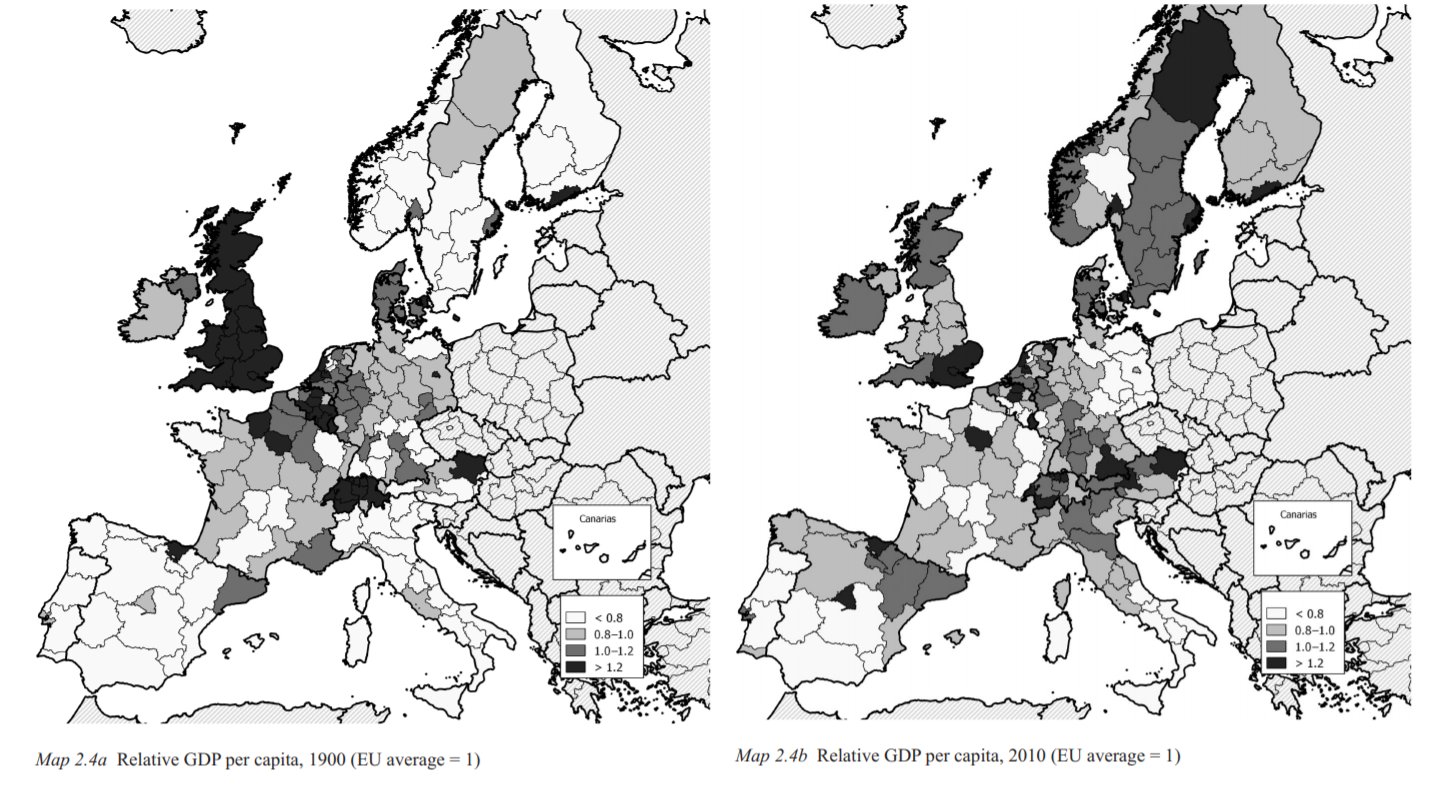

About four decades later, the original Indies (i.e. India and South East Asia) started to be called the East Indies – to distinguish them more clearly from the West Indies. East and West were defined relative to Europe. Or more precisely Western Europe, for even eastern Germans and Balts were called easterlings by mediaeval (Western) chroniclers.

That East-West divide within Europe would harden from the beginning of the 20th century, with ‘the West’ used in a geopolitical sense from World War I, denoting the Allies (Britain, France, Italy) as opposed to Germany and Austria-Hungary (although they were known as the Central Powers, not the Eastern ones). ‘The West’, in opposition to the Soviet Union, was first used in 1918, ‘the East’ as in the Communist Eastern part of Europe was first recorded in 1951.

During the Cold War, ‘the West’ was pretty clearly delineated, including all the NATO members (plus countries economically and culturally close to that alliance’s shared ideals, i.e. Sweden, Switzerland and Austria, but even Australia and New Zealand). ‘The East’, concurrently, consisted of the Warsaw Pact and affiliated Communist societies: China (“The East is Red”), North Korea, Vietnam.

The fact that the Cold War is over, not to mention the continuously diminishing global impact of Europe, will continue to chip away at the still dominant eurocentric toponymy of the world. In Australia, that ‘western outpost’ in the Pacific, ties with the ‘mother country’ (and Europe as a whole) have become so distant that Ozzies have begun referring to countries such as Indonesia, China and Japan not as the Far East, but as the Near North.

Maybe the same will happen one day in the US, when Europe will no longer be the West but the Old East and East Asia perhaps will be the New West. Not forgetting that the Chinese have never thought of themselves as eastern or western but, of course, the Middle Kingdom…

This map was sent in by Dennis J. Brennan, Sara Harrison, Kristin Kopf, and can be found here at the rather fantastic xkcd.com, “a webcomic of romance, sarcasm, math, and language”.

Strange Maps #331

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.