We Might Be Able to Survive on Mars—But Can We Live There Peacefully?

The establishment of a colony on Mars seems inevitable given just how many groups are drawing up plans for the red planet. NASA intends on sending manned expeditions in the 2030s. SpaceX has an “aspirational” deadline of reaching Mars by 2022, while Lockheed Martin hopes to establish a base camp in 2028. And outside the U.S., China claims to have developed an “EmDrive” propulsion system that would send humans to Mars in just weeks.

Still, there’s a big question that remains unanswered: What laws will ultimately rule Mars?

The answer will probably be significantly informed by current space law, which was created with the United Nation’s Outer Space Treaty in 1967.

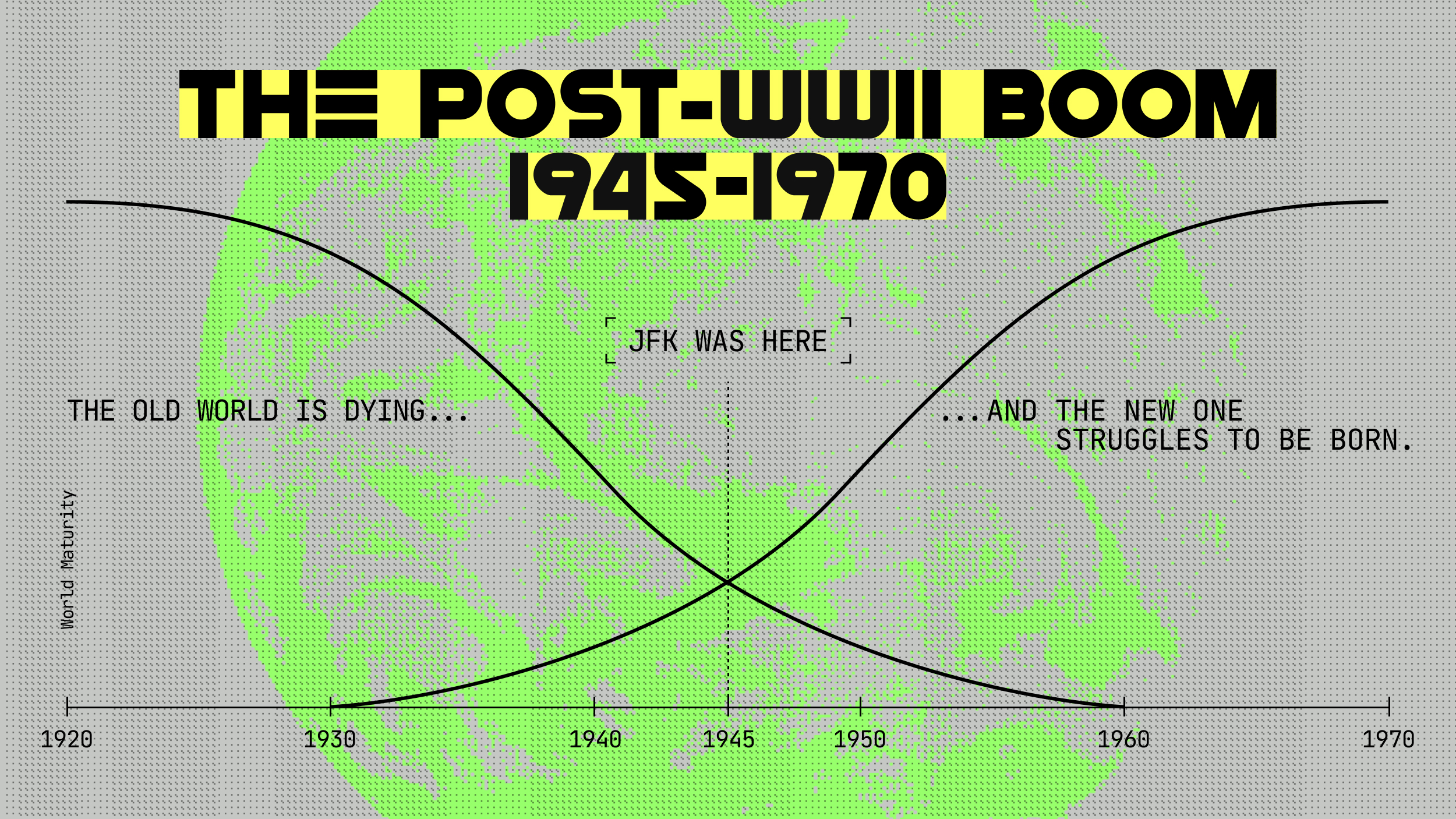

The Outer Space Treaty was largely a response to the Soviet Union’s launch of Sputnik in 1957, and its key components reflect the anxieties of the Cold War era – namely the prohibition of orbital weapons or establishing military bases on the moon. The treaty made it so the moon is under the same jurisdiction as international waters, and that any nation may use the moon for peaceful purposes. And it even says that states party to the treaty must provide all possible assistance to astronauts in the event of emergency or accident – no matter who they are.

(Strangely enough, the treaty essentially killed the development of Project A119 – a U.S. plan to detonate an atomic bomb on the moon in a spectacular display of military superiority.)

As of July 2017, 107 countries are parties to the treaty. Here’s a few more of its key parts:

Artist’s rendering of Mars colony for SpaceX

According to current space laws, space stations or objects placed on celestial bodies are subject to the laws of their country of origin. The same applies to the land that surrounds, say, a country’s base on Mars. It’s similar to how the international community views Antarctica through the Antarctic Treaty System – any nation can operate on the continent for peaceful purposes; no land can officially be claimed; and citizens and bases established on the land are subject to the laws of their country of origin.

But despite the treaty, Antarctica is effectively governed by the scientific community because there is no regulatory body present to enforce laws. This would seem to be a key parallel to a multinational settlement on Mars. However, one major difference is that, in addition to scientists, there will likely be commercial mining operations on the red planet.

Mining celestial bodies for commercial purposes is currently prohibited by space law. However, the U.S. and Luxemburg have already passed legislation regarding commercial space mining that basically says: you mine it, you own it. Several U.S. companies – Deep Space Industries, Planetary Resources, and Moon Express – are drawing up plans to do just that. It’s hard to tell how the international community will react, or if new international agreements will need to be reached, if or when commercial space mining begins.

As far as civil and criminal jurisdiction on Mars, the only legal precedent comes from the Intergovernmental Agreements of 1988 and 1999 that govern the Columbus Space Station Project and the ISS. The agreements allow for the punishment of crimes, registration of space objects, safety of nationals and repatriation of offenders to Earth.

However, those agreements don’t seem to be very analogous in practice. On the ISS, a strict hierarchy places power in the hands of one commander, much like older bodies of law regarding ship captains. There’s no indication this kind of strict hierarchy of power would exist on Mars. Moreover, there’s really no telling how Martian colonists will handle conflicts and crime on the red planet. It raises many questions: Will there be courts? Prisons? The death penalty?

What laws should be in play if, say, a ship belonging to a French mining company damages a base belonging to the Russians? And even if the international community back on Earth were to agree on a Martian legal system, what’s it going to do if the colonists decide they want to form their own laws?

This has led some to predict Mars settlements will be similar to those of the Wild West, as Stephen Petranek, author of “How We’ll Live on Mars,” told National Geographic:

“Who’s going to stop somebody if there’s a private company that wants to go on the opposite side of Mars and they want to just drill into the side of Mars and see what they can find. Who’s going to stop them? There’s not going to be anyone to stop them. It was the same way in the American West. Law was the last thing to arrive. Rules were the last thing to arrive. Justice was the last thing to arrive. Mars is likely to become very much an unruly place.”

“The people who ultimately end up owning the territory on Mars will not be countries on Earth,” Andy Weir, author of “The Martian,” told National Geographic. “It will be the people who live there.”