Liberal Education as Civic Disengagement?

So I want to call your attention to a fine article by Jonathan Marks in Inside Higher Ed, the daily online newspaper of higher education. Marks writes at a level several pay grades higher than most educational experts, and he contributes memorably to the continuing project of deconstruction of the “cant” or pretentious nonsense spewed forth daily by most of those experts.

I’ve written before against the experts who want to reduce higher education to the acquisition of a set of measurable competencies required to become a productive member of our workforce. There’s nothing wrong with becoming competent, but higher education is more than that.

Higher education isn’t mainly about becoming an engaged citizen either.

People should be both responsibly productive and good citizens. They should also be loving spouses and parents and reliable and devoted friends. They should care for the unfortunate and do what they can to sustain the environment. And they should, of course, pay due attention to their health. They should, of course, not be indifferent to or thoughtlessly deny the existence of God. If they have the gift of faith, they should lovingly serve the God in whom they believe.

We can hope and even reasonably expect that someone with a liberal education would have all those virtuous qualities required to flourish as a truthful and relational being in a free society. Liberal education is certainly about inquiring into who each of us is and what each of us is supposed to do. But it does so in a relatively disengaged way.

I don’t think, as some do, that liberal education is all about the questions and not about the answers. But it is about really asking and really, really thinking about the questions before you think you have the answers. The expert temptation today is replace thought with engagement. Engagement—being a good citizen—is a responsibility we all share in a democracy. But you shouldn’t get college credit for it.

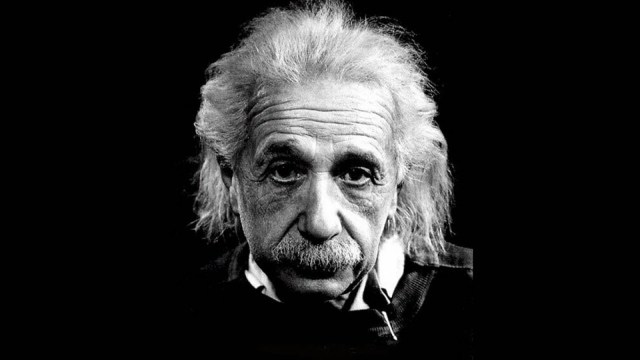

So Marks says Socrates should be at the center of liberal education. But even Socrates should be, I think, more of a question than an answer. No liberal education is complete without reading Nietzsche on “the problem of Socrates.” Or Aristophanes on Socrates’ ridiculous self-forgetfulness. Or St. Augustine on how both contemplation and charity should be parts of every person’s life. (There’s no Platonic dialogue on the charitable Socrates.) Or even Machiavelli’s not-so-veiled criticism of Socrates as a parasite who never did free people—and even free thinkers—much good at all.

The most serious Athenian citizens had some good reasons for questioning the character of Socrates’ civic engagement. He didn’t seem to care about being a citizen very much, and he was very uneven in doing his real civic duties. He also seemed indifferent to the effect his “teaching method” would have the youngest of Athenian citizens.

So we often think it was the “religious right” or patriotic nuts who were responsible for killing Socrates. But anyone who’s checked out the evidence knows that explanation is too simple.

Socrates ticked everyone off by saying he just didn’t know enough to have a complete theory of education. For good citizens, education means learning to respect and obey the law. For Socrates, they make the mistake of thinking that the law is equivalent to wisdom. But the truth is that especially democratic law is typically lacking in competence or genuine expertise. So Socrates would chasten some conservatives these days who are about the kind of “civic literacy” that present the American founding as perfect or lacking in nothing.

But Socrates equally criticized the sophists—the experts—for thinking that education is only about technical competence. They know stuff, but they make the mistake of thinking that what they know is all there is to know. A merely technical education leads to power without virtue. It makes people worse by neglecting the moral dimension of who we are. Or if “worse” seems judgmental to you, admit that it can easily make them more dangerous.

For a dumb example: Experts these days think sex education is completely about learning the techniques of safe sex—dressing up vegetables and so forth. They’re right enough that you can’t be sexually responsible without knowing the bare facts. But being good can’t be reduced to being safe. Sexual morality can’t be detached from the attendant natural and relational responsibilities. So “social conservatives” are partly right that sex education has to do with “family values.”

For human beings, education is some combination of technical competence and reasonable, relational moral discipline. The sophists are half right, but the devoted citizens are too. Socrates didn’t know enough to bring the insight of the expert with the insight of the citizen together into a comprehensive theory of education. And so he angered both the experts and the devoted citizens by saying that he—unlike them—didn’t yet think he knew enough to be an engaged educator, to provide his country the definite guidance it needed. His profession of his invincible ignorance (so far) mainly serves to chasten those who choose engagement over thought, over both technical excellence and deep moral reflection. For Socrates, the excessively engaged are typically both too confident and too angry.

So Socrates did think he had a “civic mission,” which was to remind the Athenians of what they didn’t know in such a way that that each Athenian couldn’t use that ignorance as a lame excuse not to care for one’s own soul—one’s own virtue—above all.

If our colleges and universities have a “civic mission,” it surely isn’t to change the world through students’ civic engagement. Their students and graduates, if properly educated, won’t think that they’re too wise or too free to be good citizens. But they should enter the world not thinking that they know more than they really do, and so their education should prepare them for engagement marked by the intellectual virtues of prudence and moderation. They should be free from the vanity and the anger that limits the authentic effectiveness of most political partisans.

A person with a liberal education knows that we’re all citizens, but we’re all also more than that. A person with a liberal education is not so libertarian as to believe that we can dispense with government, but is not so “engaged” or so “republican” as not to respect the limits of government. For one thing, all social engagement isn’t and shouldn’t be political. The virtue of charity, after all, is much more personal—more relational and more loving—than the virtue of justice.