What is the Big Idea?

Here’s a thought: the Middle East is one of the most resource- and culturally rich, geo-strategic and, alas, unstable pieces of ‘real estate’ on earth. Evidently, it is also a region whose leaders remain largely oblivious to the great potential of the Middle East as an integrated unit, or to the prospects of stable and lasting peace through collective defense and cooperative security.

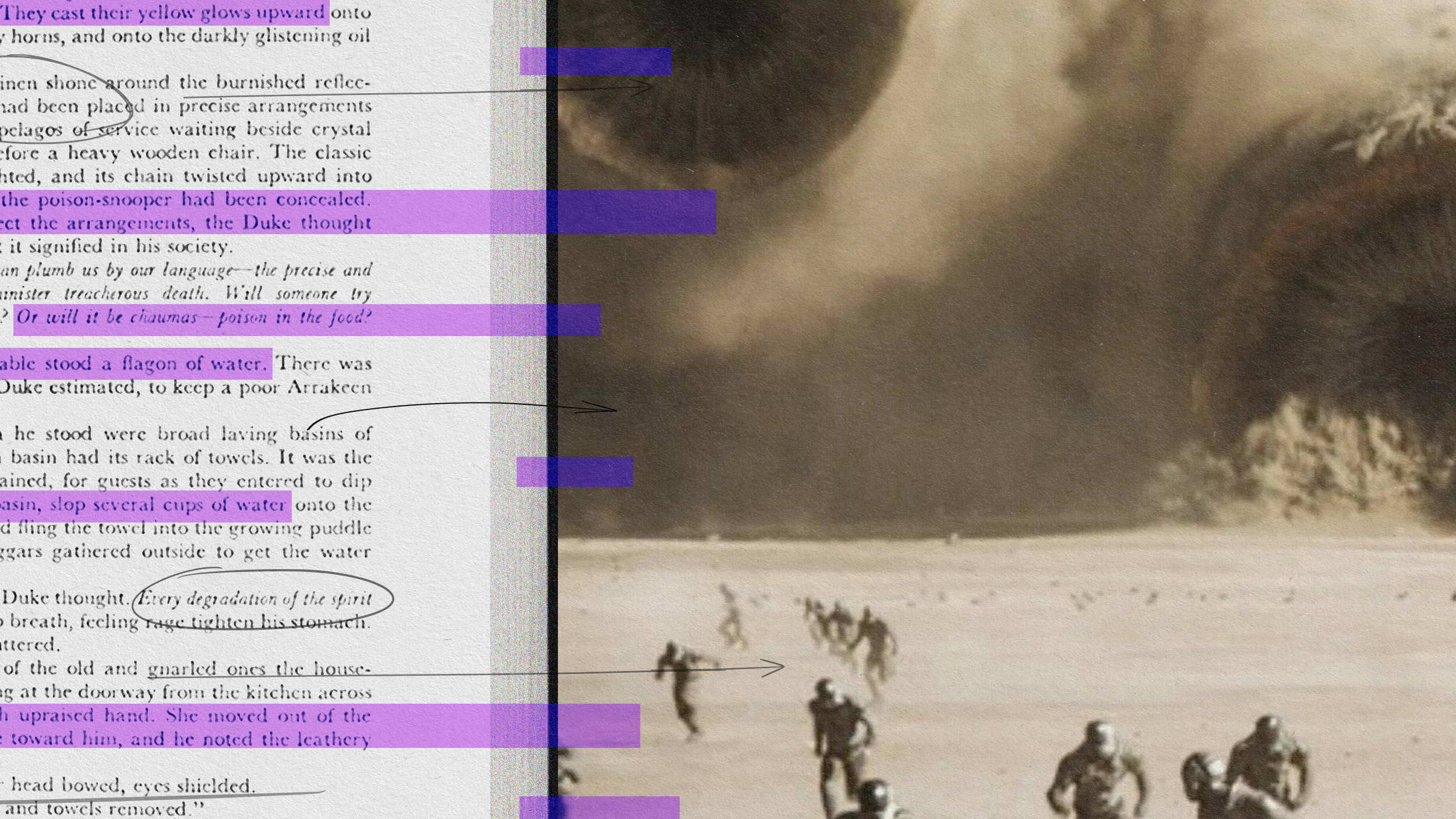

Instead, the region’s seemingly unshakable divisions have ensured a modern history marred with fierce zero-sum inter-state competition, war and turmoil, and incessant regional tensions—some, along archaic tribal or sectarian fault-lines. All of this is undergirded by the fact that the Middle East suffers from a region-wide security dilemma.

Despite these conflagrations and regional tribulations, the Middle East remains, in 2012, the only region in the world without a region-wide security and cooperation framework. This deficit must be remedied, and the timing may well be –of necessity–ripe for such a remedy given ever-escalating tensions within and between some of the region’s major powers.

The status quo and the existing approach to Middle East security are neither sustainable nor capable of bringing peace and stability to the region.

What is required is a new security formula based on a holistic framework that recognizes the region’s geopolitics and interconnectedness, as well as the realities on the ground. Armed with this important recognition, the aim should be to establish a region-wide security structure for the Middle East. Think a cocktail of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe and NATO style security arrangements by and for the Middle East.

As empirical evidence has now shown, we don’t prosecute wars out of an intrinsic human want, nor do we need to resort to the most violent behavioral expression – as is war – to best advance our interests. As Harvard psychology professor, Steven Pinker rightly argues, we are “equipped with faculties that pull us away from violence such as empathy, self-control, a moral sense, and reason.” Above all, it is this last virtue – reason – which differentiates man from the animal world, and it is reason which can parse fact from fiction; privilege diplomacy and dialogue over violence and endless animosity, and find alternative conceptions of interest maximization and security which are mutually auspicious.

It is indeed reason which can lead us to recognize that our security does not necessarily have to come at the expense of others, and that a pluralistic, all inclusive collective security framework, in which members retain and respect each-others’ independence and sovereignty, is preferable to the win-lose formula existent in the Middle East today.

What I am suggesting is not premised in some utopian, Kantian world view of international affairs. It is neither a call for a regional Leviathan which, by definition, will require the surrender of sovereignty. Rather, I posit that the creation of a region-wide security architecture in the Middle East can align raw security interests—as a vital national interest— of all regional states, and act as a game-changer by constructively altering the geopolitical calculus of homogenous, as well as exogenous actors with a vested interest in the region, in favor of collective security. Such reordering can make war unthinkable in this imagined community and repugnant to one’s own national interests. In time, peaceful relations will equally beget a host of benefits for the region’s progress and development.

What is the Significance?

Here are some of the chief hallmarks of the proposition.

A region-wide security framework is capable of offsetting the region’s security dilemma.For the security framework to work, it must be all-inclusive. That is, it must, in addition to all the Arab states, also include Israel, Iran and Turkey, to start with (Afghanistan, India and Pakistan are additional candidates due to their geographical proximity to the region, and the latter two countries’ nuclear programs). The geopolitics and realities of the region simply require this inclusivity. With leadership, assembling all Middle Eastern states, including regional rivals, to sit at a negotiating table to explore regional security is possible. In a state’s calculations on how to conduct its international relations, the contest between ideology and national interest will almost always tip the scales in favor of the latter. There are countless historical examples from the Middle East alone which give credence to this proposition.The initiative to explore and negotiate such a regional framework, and its creation, must be indigenous.The US and other external states – say China – can have a supportive role to play in the negotiations and implementation of the security framework, provided their role is secondary and governed by the limits prescribed by the states in the region. While due to historical experiences the US is unpopular in many Middle Eastern states, its involvement may be both inevitable and necessary for the security architecture to be realized. To be sure, certain Middle Eastern states will insist on US participation to provide security guarantees as a precondition to entering into the framework, and as it relates to the collective defense component of the security framework – Israel and the majority of the Persian Gulf Arab states fall in this category. For the US to be accepted across the board, it must aim to improve relations with countries in the region it has previously aimed to isolate through its containment policy and recognize and address their equally legitimate security concerns (Iran is a case in point). The role of exogenous actors can be reduced and terminated over time as trust builds and relations amongst Middle Eastern states become increasingly integrated.The impact of a regional security framework on facilitating a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is not insignificant. This contention hinges upon the assumption that the ability to provide comprehensive and lasting security guarantees to Israel–courtesy of a robust, all-inclusive regional security architecture with teeth –is key to obtaining the necessary concessions and gaining concrete ground towards realizing a viable state for the Palestinians. As such, negotiations over the latter should be coupled with those exploring a regional security framework.Similarly, a concrete security framework, which is capable of providing comprehensive security guarantees to all states in the region, can make the idea of creating a nuclear and Weapons of Mass Destruction Free Zone (WMDFZ) in the Middle East a more plausible notion. Hence, negotiations over a WMDFZ, to take place later this year in Finland will do best to incorporate discussions over the establishment of a regional security architecture for the Middle East.Tied to the preceding point, a region-wide security framework and negotiations over its establishment may help defuse and resolve tensions over the nuclear programs of Iran and Israel, without resorting to a catastrophic war.The security framework must adopt founding guiding principles, using the UN Charter, and precedents like the Decalogue contained in theHelsinki Final Act (1975) as deemed appropriate.A security framework, which benefits from a founding treaty and established set of rules, as well as organizations and institutions to enforce these rules, will create an environment in which security concerns and threat perceptions can be effectively signaled, openly communicated and processed in an institutionalized fashion, without the outbreak of war.Democracy and open space for a vibrant and healthy political discourse suffer at the national level in the absence of peace and security at the regional/international level. A regional security framework for the Middle East and its potential for enduring peace can support indigenous and sustainable political reform in the region (without the taint of foreign intervention or meddling).Lastly, Kissinger once said, “[n]o foreign policy – no matter how ingenious – has any chance of success if it is born in the minds of a few and carried in the hearts of none.” It is absolutely essential for courageous leaders, academics and civil society, first and foremost from the region, to support and further debate this proposition – through inter-state discussions, additional Track II diplomacy initiatives, conferences, university lectures,… – in the hopes of making it the topic of discussion and the lingua franca of diplomacy in the Middle East.If we want to see the change we seek blossom in our times, neoteric thinking must lead the way.

There is no honor in war, only in peace making.

Sam Sasan Shoamanesh is the co-founder and managing editor of Global Brief. He is currently a SPILS fellow at Stanford University where he’s focusing his empirical research on regional security in the Middle East.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own.