The 2-step “loci method” for memorizing absolutely anything

- Memory athletes use mnemonic strategies, specifically the method of loci or memory palace technique, to remember astonishing amounts of information.

- This method, which involves associating information with visual imagery in familiar spatial environments, leverages the human brain’s evolved skills in visuospatial memory and navigation.

- Researchers have found that, with practice, even individuals with average memory capabilities can significantly improve their memory performance using this technique.

You sit at a card table and a dealer lays out ten cards face up. He puts them back into the deck. Could you remember which cards you saw? What about in sequential order?

In 2002, Dominic O’Brien earned a Guinness World Record for reciting a sequence of 2,808 cards (or 54 decks) after seeing each card only once, making just a few errors in the process. That probably sounds like an impossible cognitive feat if you’re the kind of person who has trouble remembering where your car keys are. But for World Memory Champions like O’Brien, it’s routine fare. These so-called memory athletes can memorize stunningly large numbers of things: Rajveer Meena correctly recited 70,000 digits of pi. Ryu Song I was able to memorize 4,620 random numbers in an hour. And Katie Kermode memorized 224 unfamiliar names and faces in 15 minutes.

What’s the secret?

“Surprisingly,” notes a study published in Neuron, “such memory skills do not seem to be associated with extraordinary brain anatomy or general cognitive superiority.”

Instead of relying only on innate ability, memory athletes enhance the performance of their memories through mnemonic strategies. Such techniques include the use of acronyms (like ROYGBIV, to remember the colors of the rainbow), chunking (like breaking down a 10-digit phone number into three parts), and associating information with visual imagery.

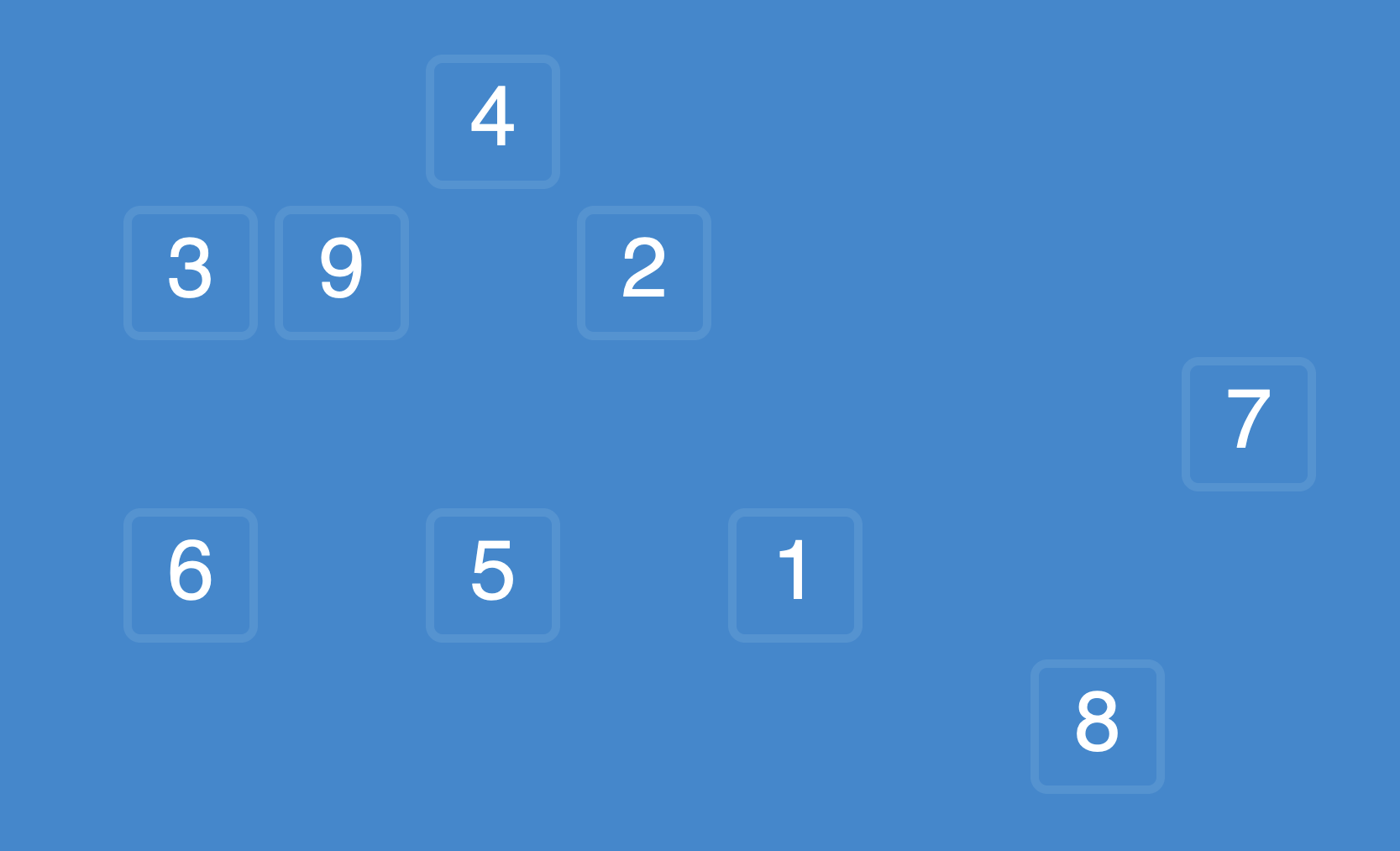

The most commonly used technique among memory athletes is the method of loci. It’s a mnemonic strategy where you form a mental image of the information you want to remember and then associate that image with a specific location on a “mental map” — a visualization of a familiar spatial environment, like your childhood home, the street by your office, or the aisles of your local grocery store.

The technique — also called the memory palace method — takes advantage of the fact that the brain remembers images more easily than words, a phenomenon known as the picture superiority effect. And like many intellectual traditions, it comes from the ancient Greeks.

The method of loci

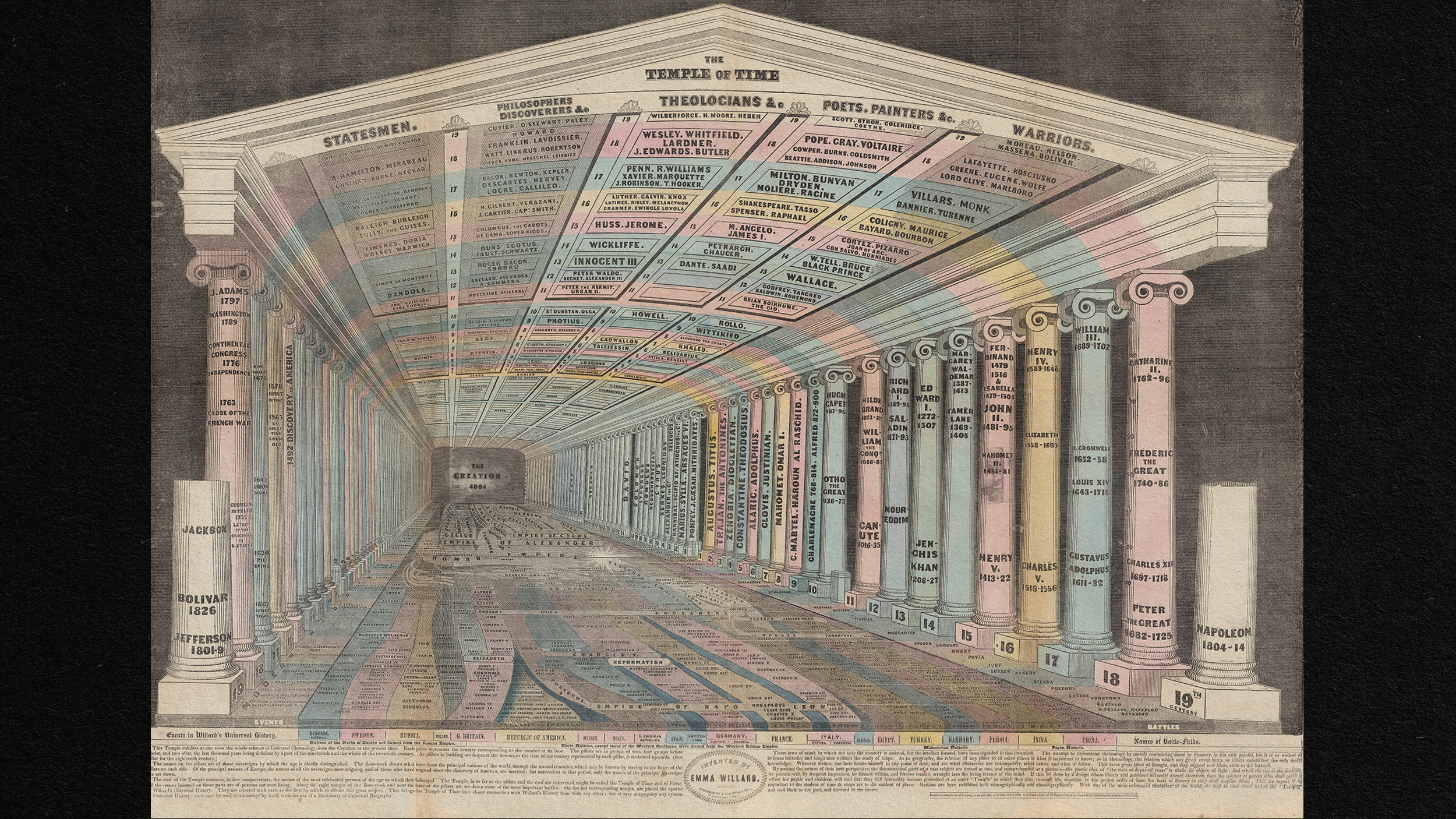

Simonides of Ceos was not only a polymath, poet, and musician in ancient Greece, but also a contender for history’s luckiest dinner guest. In “De Oratore,” the Roman writer Cicero tells the story of how Simonides was once attending a banquet in the 5th century BC when he was called upon to leave the party and briefly meet with two men outside. Soon after he stepped out, the building’s roof collapsed and killed all the attendees, leaving their bodies mangled beyond recognition.

But Simonides found he was able to identify the dead by thinking about where each person was seated at the banquet. Spatial location, he realized, can be a powerful memory aid. That’s how Simonides invented the method of loci, according to ancient sources. The Greeks and the Romans were particularly interested in specialized memory techniques — not so they could count cards or win memory championships, but so that orators could memorize long speeches without fail. (In no small way, the history of memory methods is the history of rhetoric.)

In The Art of Memory, the British historian Frances A. Yates notes that one of the most important texts on ancient memory techniques is Ad Herennium, penned by a teacher of rhetoric whose name is unknown. The teacher outlined how the ancient Greeks and Romans conceptualized memory, writing that every human is born with two types: natural and artificial. Natural is the type we each have from birth, enabling us to form and recall memories without conscious effort. Artificial memory, in contrast, is strengthened through practice. In the method of loci, this training process involves two elements: places and images.

How to build a memory palace

The first step is to visualize a familiar spatial environment — a “memory palace” that includes not just one place but rather an ordered sequence of locations (or loci) so that you’re able to start from any particular locus in the series and effortlessly move forward or backward. Derren Brown — an English illusionist who uses the method of loci in magic tricks, such as by memorizing the order of cards in a deck — explained how to build a memory palace in a 2020 interview with Big Think.

“It could be your street; it could be the walk from the subway station to your house,” Brown said. “All you need along that area are a few set points that you can remember without having to think about it.”

The set points in your spatial environment could be a mailbox, a convenience store, a peculiar tree — “just things that you’re very familiar with,” Brown said. Then come the images. For whatever list of information you’re trying to remember, pick the first thing and form a vivid image of it in your mind.

“You have to make a bizarre image of that thing,” Brown said, using the example of trying to set a mental reminder to take a suit to the dry cleaner in the morning. “[Imagine] a suit that is so clean that it’s sort of gleaming, bright white; that you can barely look at it.” You then mentally “attach” the image of the bright white suit to the first location in your memory palace — say, a mailbox along a familiar street. And you repeat this process of pairing bizarre mental images to specific locations in your memory palace for every piece of information you want to remember.

“As long as you’ve made those images as bizarre and ridiculous as I’m making them sound, which is what’s important, all you do the next day is you just mentally walk down that route again and you go, ‘Why is there a white suit on the — oh yeah, I’ve got to take my suit to the [cleaners].’”

The method of loci is useful for everyday tasks, like memorizing a simple to-do list. It can also be expanded to memorize long lists of information; it’s just a matter of expanding your mental map. For example, Brown said he often visualizes a long route through the city of London to memorize up to hundreds of things. To count cards, Brown said he visualizes a sprawling Florentine house.

“When I play cards, I visit the card room on the top floor,” Brown said in a video on his YouTube channel. “In it, I have a collection of 52 objects, each with a mnemonic link to a playing card. The clock set at seven in a dome, for example, represents the seven of diamonds.”

To count cards in four-deck blackjack, Brown said he mentally attaches three stickers to each object. As cards are dealt in the game, he mentally moves to the corresponding object and removes a sticker. If a card appears four times, he removes the object altogether. When he needs to determine which cards remain in the deck, he mentally scans his 52 objects and takes inventory. “Then I know when to play for high stakes.”

A surprisingly attainable skill

This sounds complicated, but it might be easier to develop this ability than you think. In the aforementioned Neuron study, researchers used fMRI to compare the brain activity and memory performance of world-class memory athletes with “naive controls” (read: everyday people with average memory capabilities).

The results revealed clear differences between memory athletes and non-athletes in terms of how regions of the brain communicate with each other. Memory athletes showed a “superior memory connectivity profile network” among brain regions like the default mode network, visual networks, and medial temporal lobe.

But more surprising was how some of the “average” participants were able to improve their memory through the method of loci. Across a series of word-memorization tests over six weeks, non-athlete participants who had started practicing the loci method significantly outperformed two control groups who did not.

And the fMRI results showed that as this group’s performance improved, the ways in which various brain regions communicated and worked with each other — a process known as functional connectivity — increasingly resembled the brain activity patterns of memory athletes. Mnemonic techniques, the researchers wrote, seem to “reorganize the brain’s functional network organization to enable superior memory performance.”

So why is the method of loci, in particular, so effective? One hypothesis is that the method boosts memory by tapping into a couple of the brain’s naturally evolved skills: visuospatial memory and navigation. In other words, it serves as a cognitive “shortcut” for remembering things because it takes information out of the abstract realm and into a vivid world of images.

The human brain is well-equipped to navigate this realm. For millions of years, the survival of primates has depended on the ability to recognize and remember spatial details within a rich, three-dimensional environment, whether it was the locations of safe shelters, the faces of people in the tribe, or the best spots to find food. So when trying to memorize thousands of digits of pi, or simply the names of people at a dinner party, you would do well to tap into the brain’s ancient aptitude for spatial and visual memory.

An earlier version of this article misstated the number of unfamiliar names and faces that Katie Kermode memorized in 15 minutes. The correct number is 224.