Our expectations can create fake short-term memories

- Memory is not static. Instead, it is “reconstructive,” which means that people actively alter the information they remember.

- It was thought that short-term memory is not subjected to this sort of distortion.

- But a series of experiments suggests that even short-term memories involving the letters of the alphabet can be distorted by prior expectations.

About 90 years ago, the British psychologist Frederic Bartlett published a landmark study that permanently changed how we think about memory. Taking inspiration from Chinese whispers (a.k.a. the children’s game “telephone”), he asked his participants to read a Native American story called “War of the Ghosts” and tell it to others, each of whom was then asked to retell it to somebody else.

Bartlett noticed that the story changed with each retelling. The story was unfamiliar to the participants, and so they adapted and embellished it in line with their own cultural knowledge. Bartlett therefore concluded that memory is “reconstructive,” and that people actively alter the information they remember, according to their existing biases and expectations.

The reconstructive nature of memory is now widely accepted. It is, however, still widely assumed that short-term memories are not subject to these processes, and that they represent our perceptions far more accurately. But a recent study shows that our expectations can also influence memories formed just seconds ago.

Testing short-term memory

Short-term memory (STM) refers to the ability to retain small amounts of information for short periods of time. It is thought to have a capacity of about seven items, which can be retained and used for up to about 30 seconds. This information can be transferred to long-term storage if “rehearsed” for longer; otherwise, it is forgotten.

Marte Otten of the University of Amsterdam and her colleagues set out to investigate whether prior knowledge can reshape perceptions across the short time scale in which short-term memory functions. They published their results in the journal PLOS ONE.

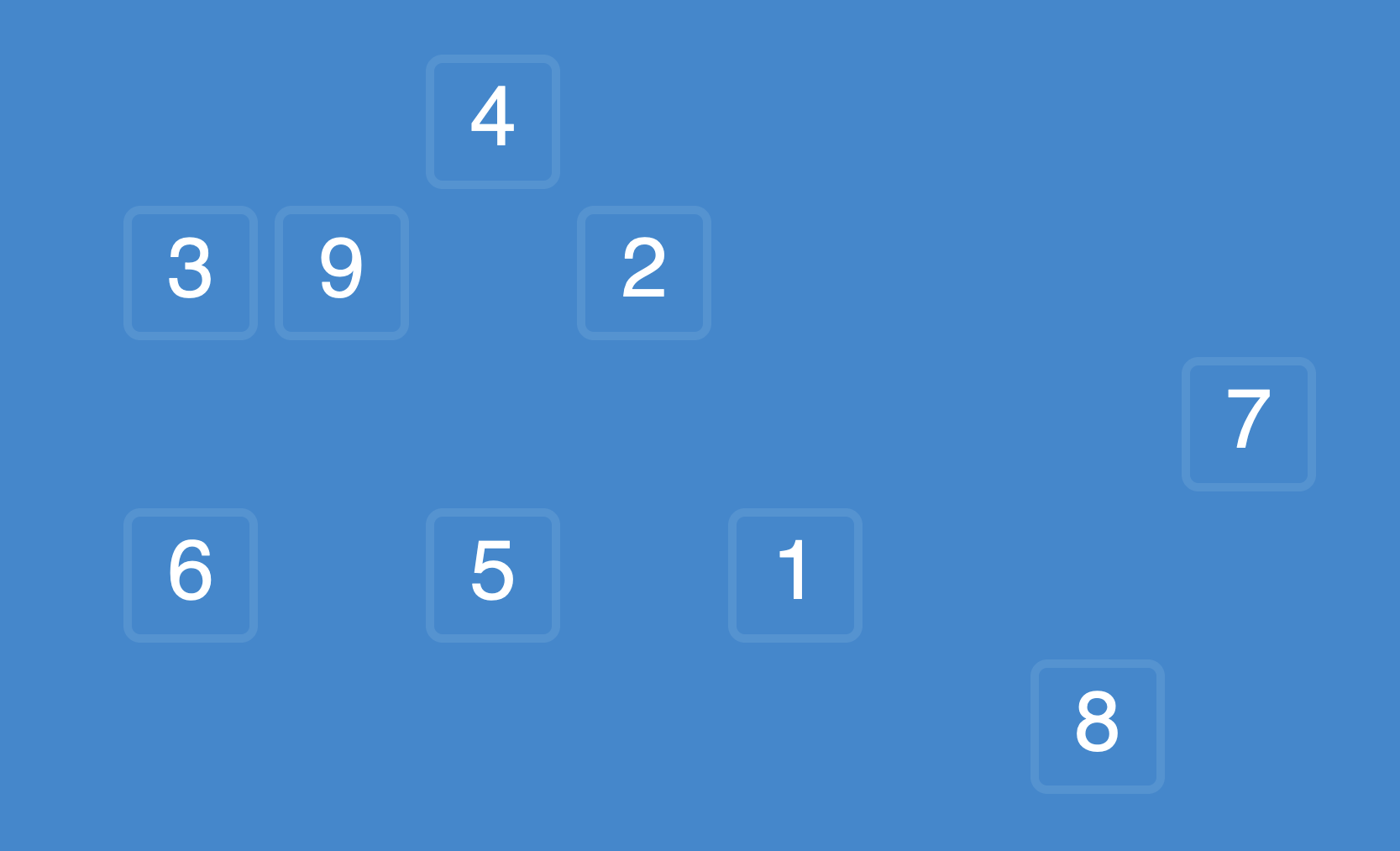

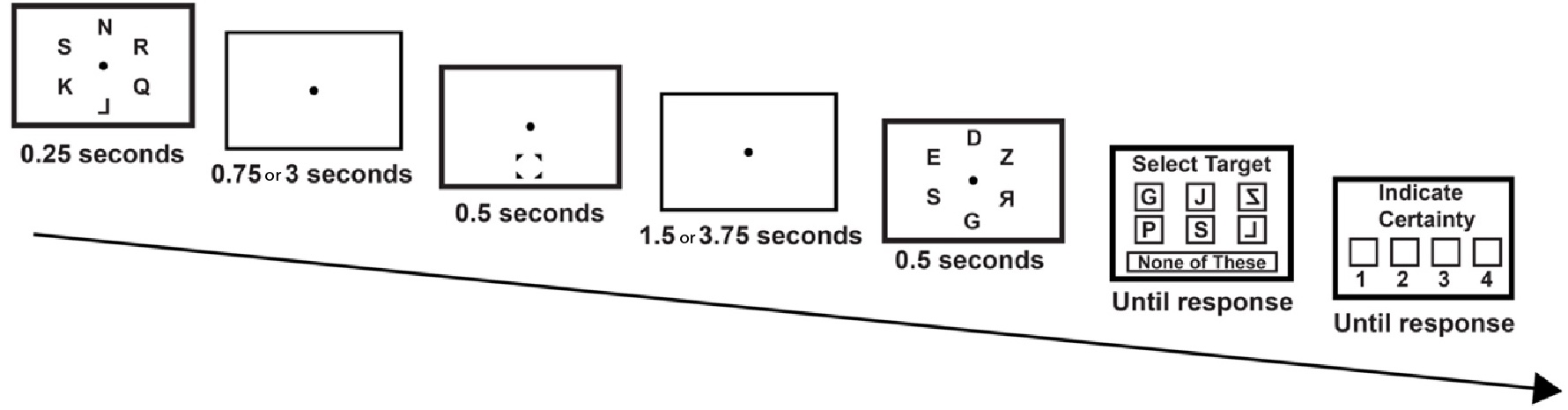

In four experiments, participants saw displays containing small sets of real letters and mirrored

“pseudo-letters,” such as “Ɔ.” Each display appeared for one quarter of a second, after which a memory “probe” that focused their attention to a specific location was presented. They then saw a second letter display, and next were asked to report the letter that had appeared in the probe’s location in the first display. They were also asked to assess their confidence in their answer. (See the figure below, which diagrams the methodology.)

The researchers observed a high rate of what they call memory illusions, whereby participants consistently reported seeing the real letter counterpart in the location of a pseudo-letter. These illusions occurred even though the letters had just disappeared from their vision, and even when the participants were highly confident of their answers. Furthermore, the pseudo-to-real letter illusions occurred more frequently than real-to-pseudo letter illusions, leading Otten and colleagues to conclude that the illusions are the result of the participants’ expectations after life-long exposure to the letters of the alphabet.

The frequency of illusions also increased with time. The memory probe was presented at varying intervals, so that it appeared before, during, or after the interfering second letter display. Illusory memories occurred about 20% of the time when the probe was shown half a second after the first letter display, and almost 30% of the time when it was shown three seconds after it. This further suggests that existing knowledge can convert just-formed memories into illusions.

Predictive coding

The researchers explain their findings in terms of predictive coding, according to which “top-down” information influences our perceptions and thought processes. In other words, our perceptions don’t occur in a vacuum; they are influenced by our memories. Because people have extensive experience with the letters of the alphabet, our brains predict that we will see real letters, not pseudo-letters, even when sensory information shows otherwise.