Bilingual people who know a different alphabet have unique brains

- New research suggests that the brain of a bilingual person who knows two alphabets is different from that of a bilingual person who only knows one alphabet.

- The differences occur in a region called the visual word form area (VWFA).

- Bilingualism confers various mental health and social benefits. Perhaps knowing a second alphabet confers even more.

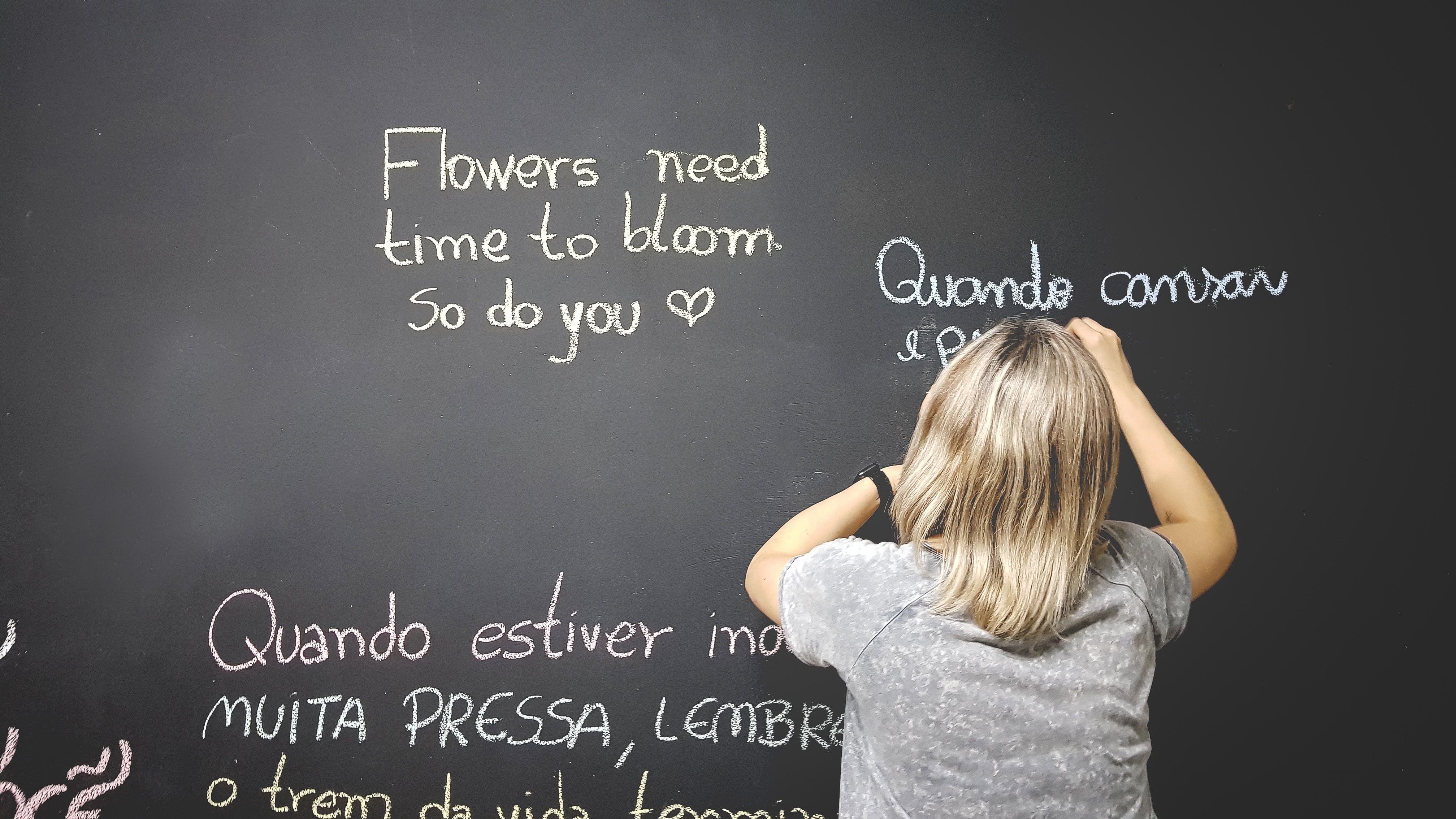

English and French are different languages that use the same alphabet, but Chinese uses an entirely different one. New research suggests that the brain of a bilingual person who knows two alphabets is different from that of a bilingual person who only knows one alphabet. The research, which has not yet been peer-reviewed, has been published to the BioRxiv preprint server.

Visual word form area

When we learn to read, a small region of the cerebral cortex becomes highly sensitive to the letters and words of the script. This region lies within a patchwork of regions, each specialized to recognize a specific category of visual stimuli, such as faces or objects, based on their geometric features.

Known as the visual word form area (VWFA), this region is found in the same location in the brain in readers of all languages. It also is organized hierarchically, with its sensitivity increasing from the back of the brain to the front, and it responds most strongly to strings of letters that match real words.

Minye Zhan of the Paris-Saclay Institute of Neuroscience and her colleagues used high-resolution functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to examine the organization of the VWFA in 31 bilingual readers. These volunteers included 21 who read English and French, which both use the Latin alphabet; the other 10 read English and Chinese, the latter being a “logographic” script in which individual characters represent words.

In one experiment, Zhan and her colleagues scanned the English-French bilingual readers’ brains while they viewed English or French words, Arabic numerals, meaningless six-letter strings, and various objects. As previously reported, they observed a hierarchical activation of the VWFA, with the front of the region being sensitive to real words but not nonsense letter strings. There were no consistent differences between the two languages.

A second experiment with English-Chinese bilingual readers was designed very similarly to the first, except that the French words were replaced with Chinese characters as well as nonsense characters derived from them. This, too, revealed hierarchical activation, with the front of the VWFA being selective for real words.

This time, however, they also observed small patches of cortex that were specialized for Chinese words. These patches were selectively activated by real Chinese words but not by real English words. (They did observe some small patches specific to English words, but there were fewer of these, and their specificity was weaker than the Chinese-specific patches.)

Alphabet on the brain

These specialized “word patches” were found to be present in both hemispheres, at the bottom of the junction between the occipital and temporal lobes. In most of the participants, they were found to be more numerous, and larger, in the left hemisphere.

Crucially, some of the word patches were highly selective for Chinese words. These patches often overlapped with, or were physically very close to, clusters of cells that were selectively activated by faces. The researchers suggest that Chinese characters, like faces, may require holistic processing.

It has long been known that bilingualism confers various mental health and social benefits. Perhaps knowing a second alphabet confers even more.