Philosopher Alan Watts on the meaning of life

Photo: Pictorial Parade/Getty Images

- Alan Watts suggests there is no ultimate meaning of life, but that “the quality of our state of mind” defines meaning for us.

- This is in contradiction to the notion that an inner essence is waiting to be discovered.

- Paying attention to everyday, mundane objects can become highly significant, filling life with meaning.

During a conversation with Wired co-founder Kevin Kelly, Tim Ferriss mentions the metaphor of the ice sculpture. A longstanding idea: humans are like blocks of ice. “Discovering your destiny,” as the phrasing goes, is akin to taking a pick to the block to reveal what’s inside. The problem, Ferriss continues, is that’s not how destiny works. Meaning is created, not found.

I’ve encounter this metaphor often. In the late ’90s, employed as an entertainment reporter in Princeton, I interviewed numerous sculptors. (There are a lot of wonderful sculpture gardens throughout South Jersey.) Each artist repeated the other: I’m only revealing what’s already inside this block of stone.

Years later, while I was working as a music critic, kirtan singer Krishna Das expressed a similar sentiment in regard to the human soul. Chanting wipes away impurities to expose what’s been waiting inside the entire time. This idea dates back millennia — the inner serpent energy, kundalini, is “awoken” through yogic austerities, such as intense breathing exercises and chanting. The goal is to “find out who you really are.”

The mindset assumes there’s a particular “way” we are “meant” to be. Music and sculpture are noble endeavors, beautiful paths to follow. Yet it is more likely that the artist pursued them; “destiny” relies on hindsight. While those mentioned above were genuine in their expressions, not everyone is so generous.

The next step from believing in a predestined mini-me is fundamentalism. For vegans, humans are “not meant” to eat animals. For tolerant Christians, people practicing other religions are not evil, but they’ll never reach the kingdom. (This is true of many religious.) For intolerant fundamentalists, the rest of the world is ruining it for them.

Alan Watts ~ The Meaning Of Lifewww.youtube.com

When I was studying for my degree in religion, I felt fortunate I was not raised with one. I was not tainted with a notion that “this one is right.” Sure, a few underlying principles apply to many faiths, but the conviction of rightness displayed by each is disturbing. It’s also revealing: if thousands of different factions each believe they’re stirring the secret sauce, then a belief in rightness must be the product of human imagination, not reality itself. Or, better put, their reality is produced by their imagination.

Indeed, as we’re living through in America today — alongside many other nations experiencing populist fervor — we invest deeply in our personal story. We rebel against any contrary information, unless, of course, you’ve trained yourself to honestly weigh many sides. Unfortunately, this skillset is lacking. The “reality should be this way” paradigm persists.

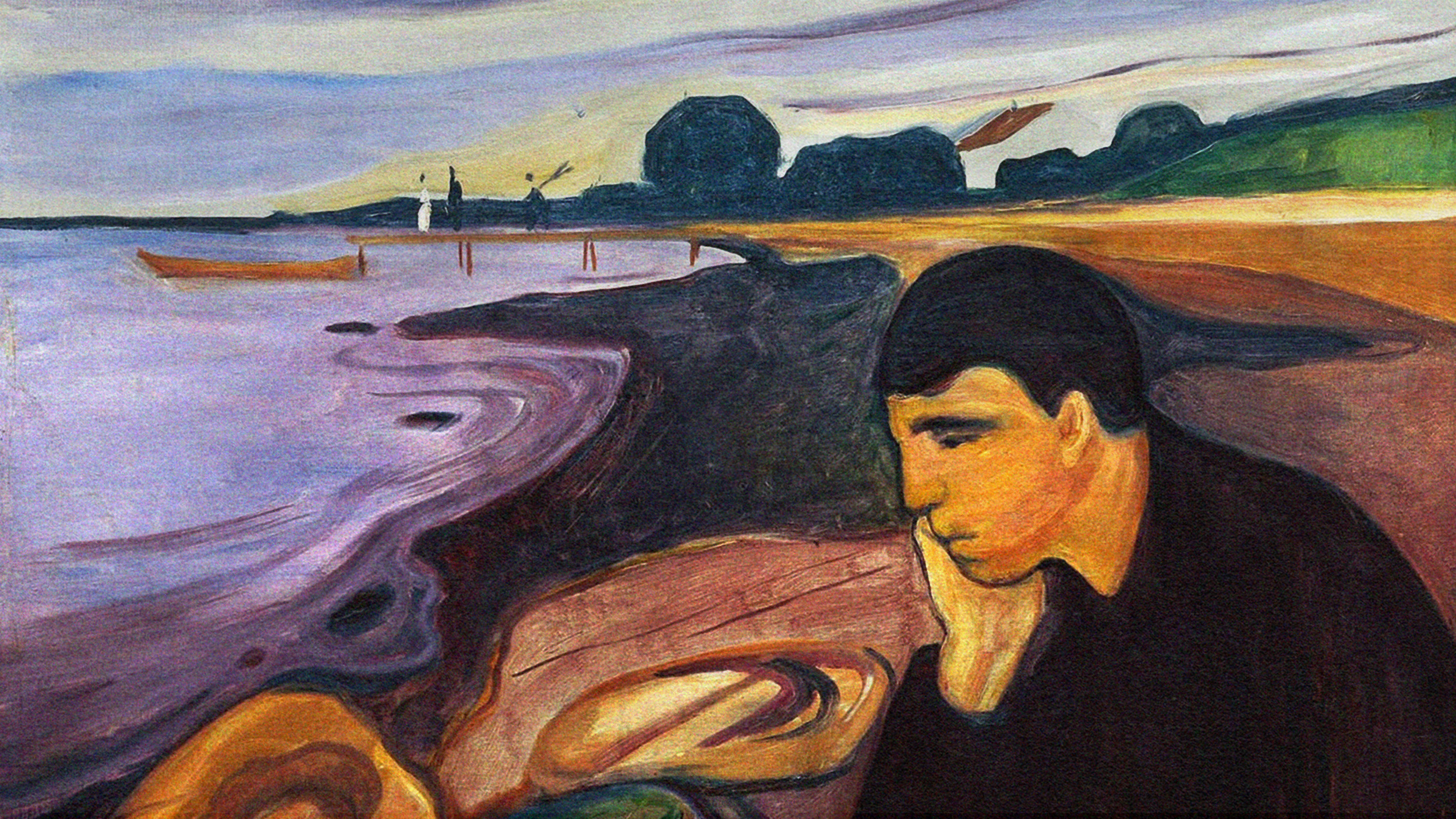

I discovered Alan Watts while studying humanity’s varied religious traditions. In the lecture above, the British philosopher mentions his church upbringing. (Watts became an Episcopalian priest for five years himself.) He recalls sermons about “God’s purpose,” yet felt uninspired by explanations of what exactly that implied. Meaning was ambiguous.

When discussing meaning in life, Watts continues, we’re not reducing reality to a “collection of words, signifying something beyond themselves.” What then would actually satisfy our quest for meaning? What could capture the ineffable if meaning was reduced to an unexplainable feeling?

“Our ideals are very often suggestions,” he continues. Rarely do we pursue what our imagination puts forth. Yet still we demand that life have significance. Groups are perfect vehicles for this: shared meaning satisfies through consensus. Yet this explanation does not satisfy Watts. How would group consensus provide a context for ultimate meaning rather than simply be the manifestation of biological, tribal impulses?

Could the landscape of reality simply be the satisfaction of biological urges? This too seems insufficient, for those urges must point to something else — another beyond. The perpetuation of life is a futuristic endeavor. Does that imply we must reduce biological processes to “nothing but going on towards going on towards going on?”

Life is NOT a Journey – Alan Wattswww.youtube.com

Watts contemplates theism. If meaning is finally derived from the relationship between God and human, what is this love driving toward? Can it ultimately satisfy? I’ve often heard it claimed that love is everything. Yet what meaning does this love hold? If you can’t explain it, but default to the usual response — you just have to feel it — that is a physiological explanation. While indeed physiology produces philosophy, it lacks in communication. If we want to point at something as meaningful, we can’t rely on others to simply feel what we feel.

Finally, Watts hits on an idea so simple, yet, as in the Zen traditions he so fervently studied, so profound. Perhaps the search for meaning is discovered by paying attention to the moment. Watts uses music as an example:

“It is significant not because it means something other than itself, but because it is so satisfying as it is.”

When our “impetus seeking for fulfillment cools down,” we allow space for the moment. By watching ordinary things “as if they were worth watching,” we are struck by the significance of objects and ideas we never previously considered significant at all. And though Watts thought psychedelics amusing yet suspect — he was more a drinker — the experience while under their influence highlights this same point.

After one particularly potent dose of psilocybin, my friend and I stood on his deck watching dozens of caterpillars launch from the roof, sliding down self-created bungee cords. For a half-hour we were transfixed by this miraculous process of creation and mobility. It’s easy to say, “well, drugs,” but it’s much harder to find the beauty of the every day when every day our faces gaze into screens instead of the world that produced them.

“Perhaps,” Watts continues, “significance is the quality of a state of mind.” Photographers shooting paint peeling from a door or mud and stone on the ground capture an essence, a moment in time, that is meaningful in and of itself. What does art mean? We stare at paintings as if a mirror, each brushstroke a moment from our biography. Hearing the artist share the meaning of their creation sometimes (but not always) ruins the experience. Art is a dialogue; meaning lies at the intersection.

Maybe, Watts concludes, “We’re overlooking the significance of the world by our constant quest for it later.” Silicon Valley futurists enthralled with life extension are missing the point; death is no longer a concern when every moment is filled with meaning. There is no hidden sculpture waiting to be revealed. It is here. You just need to see it.

—

Stay in touch with Derek on Twitter and Facebook.