Finding home in Storyland: The transformative power of books

- Writer Elif Shafak describes reading as a radical act of empathy, allowing us to live in another’s world and challenge our biases.

- Literature provides a sanctuary and an opportunity for growth, making it an essential part of the human experience.

- Books allow us to experience life beyond our own, and can leave us a with a sense of grief when they’re finished.

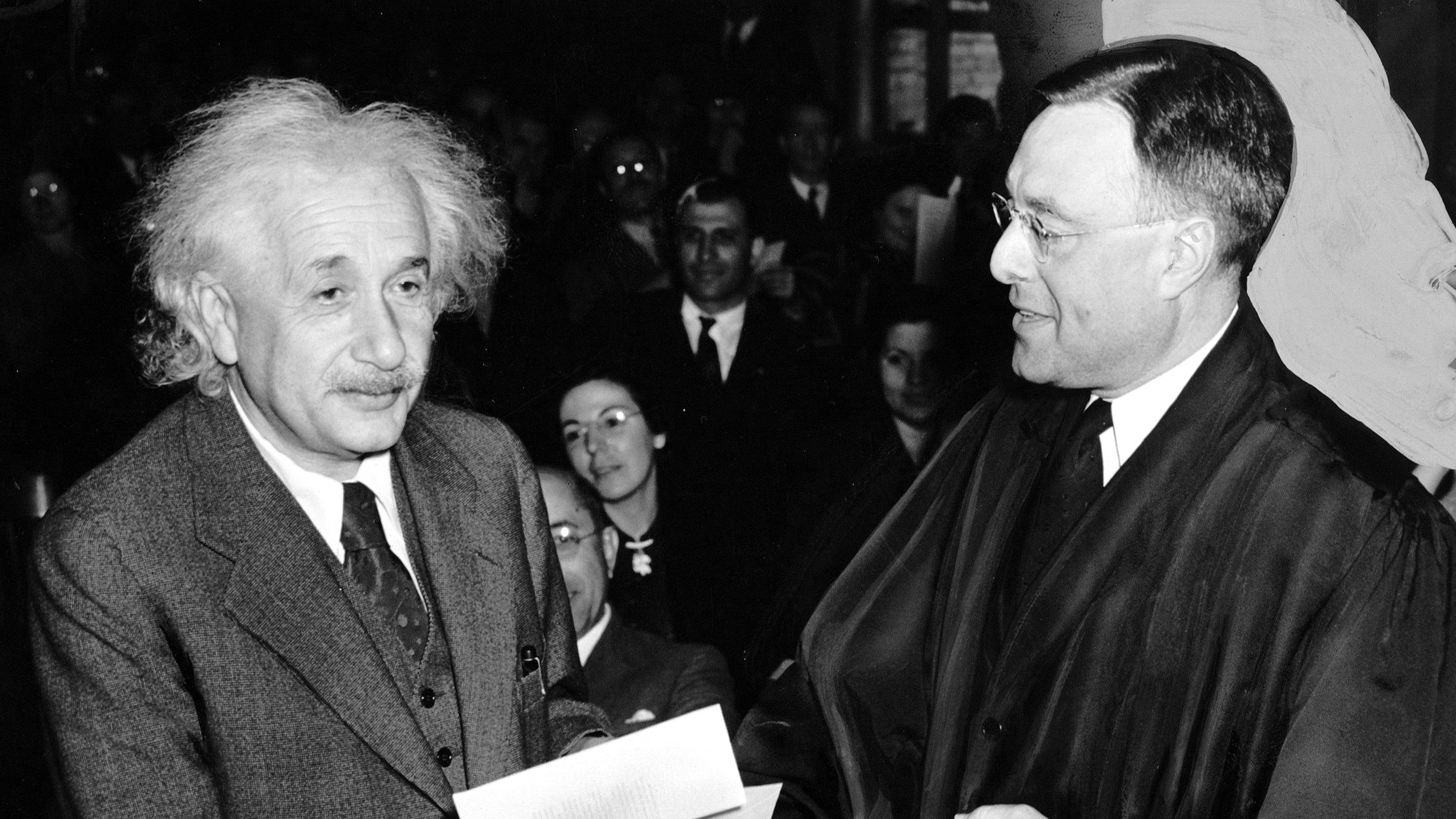

Albert L. Gordon was a homophobe. This being the early 1960s, he wasn’t alone. Gordon and his college buddies thought homosexuality was abhorrent, unnatural, and almost certainly a marker of other criminality.

One day in 1962, Gordon got a phone call from the police. His son had been arrested for soliciting an undercover cop. Could the homophobe come to the station to collect his gay son? Gordon turned his back on his son. He couldn’t come to terms with the dissonance in his life. But over the years, something changed. He started spending more time around his son and his son’s gay friends. They weren’t the stereotypes he had assumed: criminal, cartoonishly effeminate, deviant subversives. They were just people who found different people attractive.

Gordon went on to be one of the most famous advocates for gay rights in American history, and his story is one of many who learned that their hate was misplaced. It’s hard to hate those whom you get to know. It’s hard to hate people you live with and see every day.

Earlier this year, I spoke with the award-winning novelist, essayist, and political thinker Elif Shafak. For Shafak, stories are another important and emotionally impactful way to get to know other people. When we read books, we invite other lives into our heads. Or, in a metaphor Shafak prefers, we come to live in someone else’s house. When we’re there, we see that our world is not the only one.

A room in a foreign house

Shafak argues that reading a book is a radical act of egolessness. You leave the world as you know it and step into another one entirely. More than this, you start to live another life entirely. The power of great literature is that it consumes your entire being. You are possessed by the thoughts, feelings, and dramas of the protagonists. You live alongside characters, experiencing a fictional world with a multisensory depth that is irreducible to simply reading lines on a page. As George R.R. Martin wrote into his character Jojen, “A reader lives a thousand lives before he dies. The man who never reads lives only one.”

The humanistic psychologist Carl Rogers once argued that at the heart of all human relationships — as well as personal happiness — is a kind of “empathetic immersion.” We have to imagine what it’s like for someone else. We step inside their shoes and walk for a bit. For Shafak, books are a kind of Rogerian immersion.

“When we read books, we invite other lives into our heads — or, in a metaphor I prefer, we come to live in someone else’s house,” says Shafak.

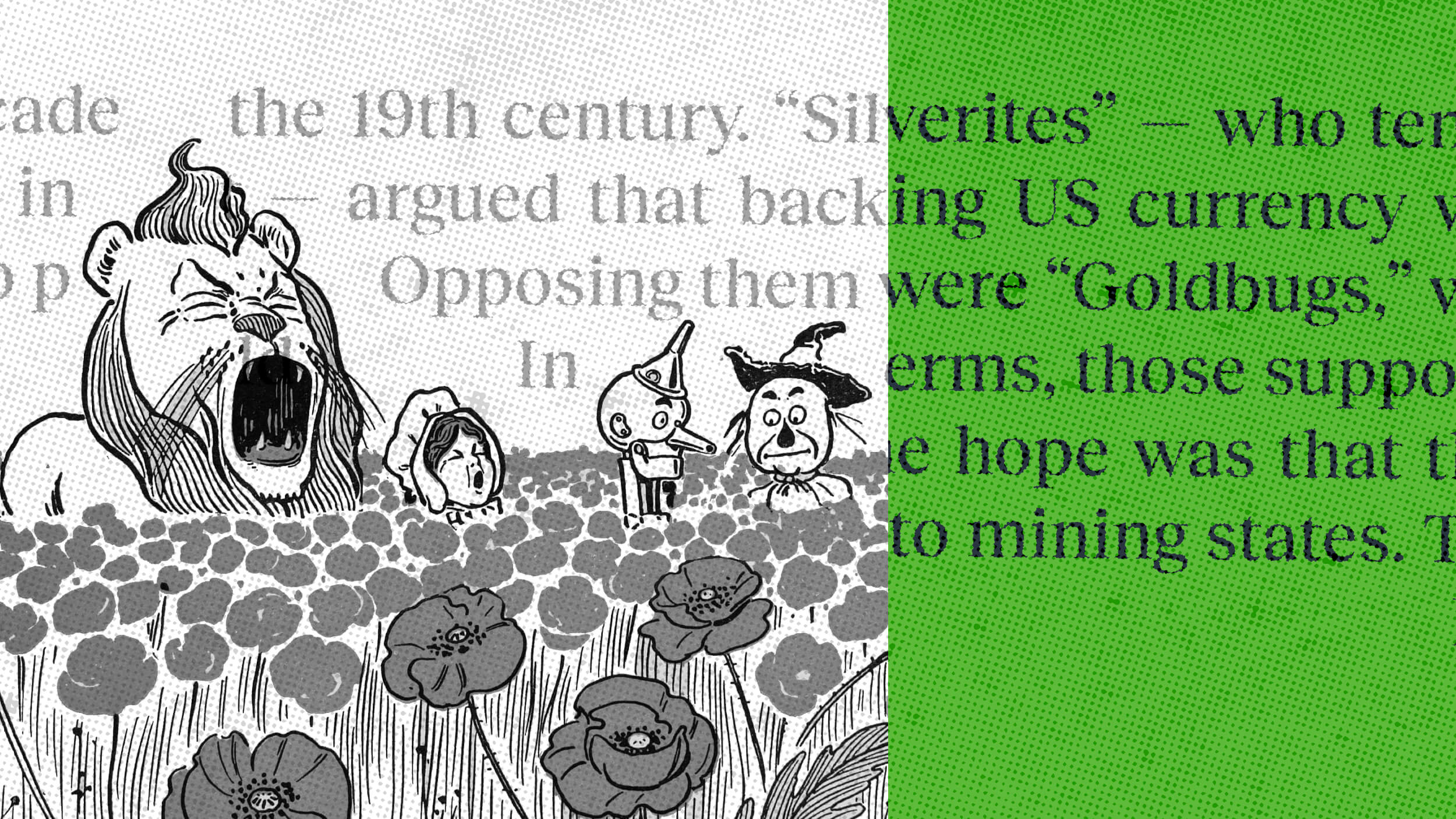

There is a twofold beauty to this. The first is the sheer luxury of choice we have. There are millions of books — millions of homes we could visit. We could read something modern and gritty and oh-so-close to reality, or we could read something about aliens or hairy-footed halflings. We could live in the heart of an ancient Roman or the mind of a Maoist revolutionary. The second is the comfort of knowing who else lives in those bookish homes. Of course, you will live alongside the characters you meet. You will live inside the soul of an author. But in the leather-bound walls of your reading journey, you will meet all of the other people who have lived there. You will find Catherine the Great reading Candide right there next to you. You will find Theodore Roosevelt annotating The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. If you read Edgar Allan Poe, you might sense Margaret Atwood, not long gone.

The houses in “Storyland” will immerse you in another way of life, and you’ll find companions who stretch back thousands of years.

A life in Storyland

Living in another’s house for any period of time might not always be easy. Some books do not make for light reading. Classic literature is often made “classic” by the tragedy and the soul-wrenching depth it explores. But “empathetic immersion” can also be difficult when it challenges our existing biases or values. It’s difficult to meet people who believe different things from us. It’s difficult to read stories of abuse, bigotry, and criminality. But these books, as much as any, will stretch us. We grow when we are challenged in this way.

At other times, though, we can enjoy ourselves so much that we choose to stay there. We dip in and out of the real world as we need to, but there is an existential pull toward story. This is how Shafak views it when she says, “For me, home is Storyland. That is where I feel at home. That is my sanctuary. That’s my exile, but it’s also my sanctuary. And I feel like I can be multiple. I can be free in that space. So if you asked me, where is home, I would always say Storyland.”

But all books have an ending, and everyone has to return to reality eventually. This transition can feel like a quiet loss, a sudden detachment from a world that had become a home. It is why some readers delay the last chapter or immediately seek another book — to soften the grief of departure. There can often be an element of grief when we end a book. We become so bonded with certain characters and so comfortable in a story’s home that we are sad to leave. We’d prefer to stay a bit longer. We might even turn back to page one.

More than escapism

For Shafak, reading is a radical act of empathy — a journey where “we come to live in someone else’s house.” In literature, we inhabit worlds beyond our own and get to experience life in all its multifaceted beauty, pain, and diversity. This is something more than “escapism.” The reading of immersive empathy is what connects us with other ways of living. It challenges our biases while offering comfort in shared humanity.

Storyland is both sanctuary and exile. It offers us countless homes and other lives. And what we find inside those homes and alongside those lives will transform us. Reading is not simply the lazy pleasure of a lounge lizard. Immersing ourselves in stories is an essential part of being human and being able to grow.