Forgotten Nazi pesticide rediscovered — it was safer than DDT

Buyenlarge/Getty Images

- DDT, or dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, was an extremely popular pesticide during World War II up until the ’70s, when it was banned.

- DDT was believed to be extremely safe, but it turns out this was only due to enthusiasm for the pesticide drummed up by its efficacy during World War II.

- Researchers have uncovered a far more effective pesticide that Allied forces wound up ignoring, in part because of its association with the German forces.

When DDT, or dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, first came into use as a commercial pesticide, it was hailed as “magic,” a “miracle,” as part of “the world of tomorrow.” As crystals of DDT come into contact with their intended arthropod targets, they open up their neurons’ sodium ion channels, forcing the neurons to fire uncontrollably and leading to spasms and eventual death. In many ways, DDT was a magical pesticide — unlike others, pests didn’t have to eat it, they just had to come into contact with it; it kept working long after it had been applied; and it seemed harmless to humans and many other beneficial insects.

But nobody uses DDT anymore because it is very much not harmless to humans and other beneficial insects. It’s incredibly toxic, and during World War II and the few years after it was applied liberally throughout American homes with no understanding of its overall environmental effects.

DDT’s half-life ranges from 22 days to 30 years — that long-lasting effect that seemed to be a boon at first turned out instead to be a curse. Agricultural runoff ensured that DDT found its way into the bodies off a variety of fish, where it accumulated and then passed on to predators feeding on the fish. It broke down the eggshells of bird species, making it more difficult for them to reproduce. Because of this, the bald eagle was in serious risk of extinction prior to the 1972 ban of DDT. In humans, DDT lowers semen quality, makes spontaneous abortions more likely, and increases developing children’s risk for autism.

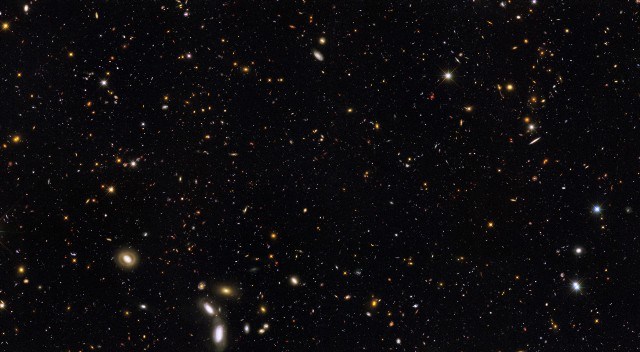

A monofluoro analog of DDT, as seen through an optical microscope. Solid fluoridated forms of DDT killed insects more quickly than did DDT.

Xiaolong Zhu and Jingxiang Yang, NYU Department of Chemistry

Rediscovering a forgotten pesticide

Of course, DDT hadn’t been universally accepted as a harmless wonder pesticide, but the general public was generally enthusiastic about its use. In part, this was because of its incredible efficacy in World War II.

Wars bring thousands of soldiers into close contact and forces unhygienic conditions. Malaria and typhus epidemics frequently lasted long after conflicts ended. In World War I’s Eastern Front alone, for instance, typhus infected an estimated 30 million. During the war, 1.5 million soldiers would also become infected with malaria. Strategists were eager to jump on any solution that could be used to hold off the lice and mosquitoes that formed the war’s deadliest fighting force.

So, despite potential environmental concerns, the short-term benefits of a pesticide made it a strategic necessity. Furthermore, DDT’s costs were more acceptable during wartime, where casualties were expected and where the risk posed by pest-borne diseases were far higher than the risk posed by a toxic pesticide. Both sides knew this. However, the Germans didn’t use DDT. Instead, they used fluorinated DDT, or DFDT.

But after the war, DFDT was relegated to the history books as an understudied, presumably less effective form of DDT. That is, until researchers from New York University stumbled across the forgotten chemical during their studies of crystallized insecticides.

“We set out to study the growth of crystals in a little-known insecticide and uncovered its surprising history, including the impact of World War II on the choice of DDT — and not DFDT — as a primary insecticide in the 20th century,” said Bart Kahr, study co-author, in a statement.

Kahr and colleagues were surprised to discover that DFDT appeared to function more effectively than DDT, killing mosquitos up to four times faster. “Speed thwarts the development of resistance,” said study co-author Michael Ward. “Insecticide crystals kill mosquitoes when they are absorbed through the pads of their feet. Effective compounds kill insects quickly, possibly before they are able to reproduce.”

Not only does a faster-acting compound mean that mosquitos and other pests are less likely to reproduce and develop resistance, but it also means that less material needs to be used, potentially mitigating the environmental concerns that led to DDT’s eventual ban.

Why the Allies forgot about DFDT

After World War II, Allied forces were skeptical of the German’s claims regarding DFDT’s faster action and reduced lethality to mammals. One particularly dismissive report read, “The German claims as to the superior insecticidal action of their [DFDT], in comparison to DDT, are not clearly supported by their meager and inadequate tests against houseflies.” Selling DFDT to the public, too, would have been a difficult task. As World War II drew to a close, news was trickling in about how another German-made pesticide called Zyklon B was being used.

Thus, DDT became the pesticide of the 20th century, even despite Paul Müller, the chemist who discovered DDT’s pesticidal capabilities, advocating for the use of DFDT in his 1948 Nobel Prize speech. While more research is needed to truly quantify DFDT’s environmental impact, one can’t help but wonder if the decades of environmental degradation wrought by DDT could have been avoided had we taken a closer look at its alternative.