Amazon fires are destructive, but they aren’t depleting Earth’s oxygen supply

JOAO LAET/AFP/Getty Images

Fires in the Amazon rainforest have captured attention worldwide in recent days. Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, who took office in 2019, pledged in his campaign to reduce environmental protection and increase agricultural development in the Amazon, and he appears to have followed through on that promise.

The resurgence of forest clearing in the Amazon, which had decreased more than 80% following a peak in 2004, is alarming for many reasons. Tropical forests harbor many species of plants and animals found nowhere else. They are important refuges for indigenous people, and contain enormous stores of carbon as wood and other organic matter that would otherwise contribute to the climate crisis.

Some media accounts have suggested that fires in the Amazon also threaten the atmospheric oxygen that we breathe. French President Emmanuel Macron tweeted on Aug. 22 that “the Amazon rain forest – the lungs which produces 20% of our planet’s oxygen – is on fire.”

The oft-repeated claim that the Amazon rainforest produces 20% of our planet’s oxygen is based on a misunderstanding. In fact nearly all of Earth’s breathable oxygen originated in the oceans, and there is enough of it to last for millions of years. There are many reasons to be appalled by this year’s Amazon fires, but depleting Earth’s oxygen supply is not one of them.

Oxygen from plants

As an atmospheric scientist, much of my work focuses on exchanges of various gases between Earth’s surface and the atmosphere. Many elements, including oxygen, constantly cycle between land-based ecosystems, the oceans and the atmosphere in ways that can be measured and quantified.

Nearly all free oxygen in the air is produced by plants through photosynthesis. About one-third of land photosynthesis occurs in tropical forests, the largest of which is located in the Amazon Basin.

But virtually all of the oxygen produced by photosynthesis each year is consumed by living organisms and fires. Trees constantly shed dead leaves, twigs, roots and other litter, which feeds a rich ecosystem of organisms, mostly insects and microbes. The microbes consume oxygen in that process.

Forest plants produce lots of oxygen, and forest microbes consume a lot of oxygen. As a result, net production of oxygen by forests – and indeed, all land plants – is very close to zero.

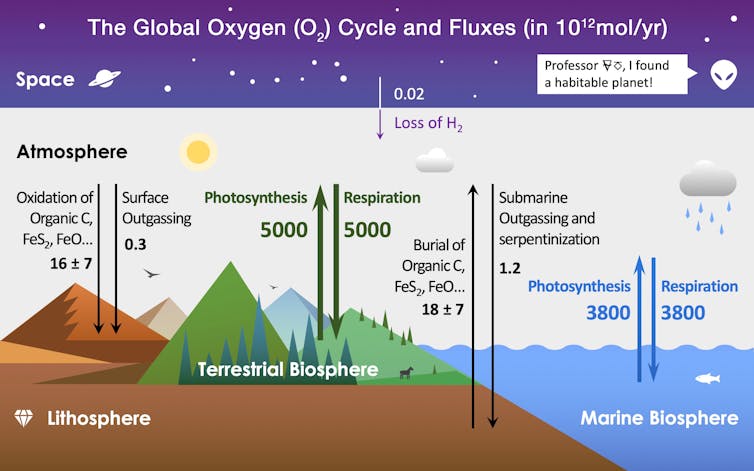

Pengxiao Xu/Wikimedia, CC BY-SA

There are four main reservoirs of oxygen on Earth: the terrestrial biosphere (green), marine biosphere (blue), lithosphere (Earth’s crust, brown), and atmosphere (grey). Colored arrows show fluxes between these reservoirs. Burial of organic material causes a net increase in atmospheric oxygen, and reactions with minerals in rocks cause a net decrease.

Oxygen production in the oceans

For oxygen to accumulate in the air, some of the organic matter that plants produce through photosynthesis must be removed from circulation before it can be consumed. Usually this happens when it is rapidly buried in places without oxygen – most commonly in deep sea mud, under waters that have already been depleted of oxygen.

This happens in areas of the ocean where high levels of nutrients fertilize large blooms of algae. Dead algae and other detritus sink into dark waters, where microbes feed on it. Like their counterparts on land, they consume oxygen to do this, depleting it from the water around them.

Below depths where microbes have stripped waters of oxygen, leftover organic matter falls to the ocean floor and is buried there. Oxygen that the algae produced at the surface as it grew remains in the air because it is not consumed by decomposers.

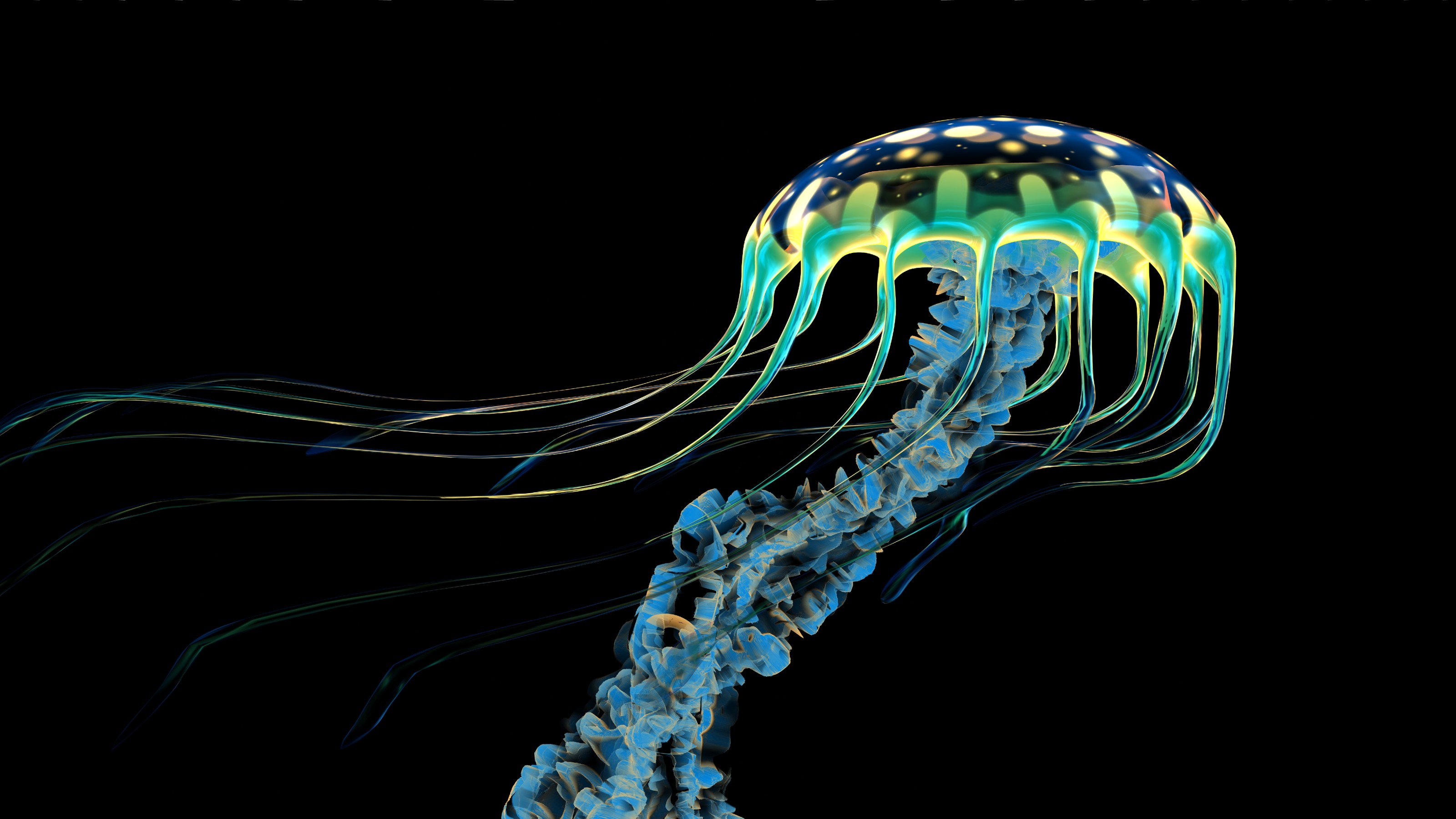

Tiny phytoplankton in the ocean generate half of the oxygen produced on Earth.

This buried plant matter at the bottom of the ocean is the source of oil and gas. A smaller amount of plant matter gets buried in oxygen-free conditions on land, mostly in peat bogs where the water table prevents microbial decomposition. This is the source material for coal.

Only a tiny fraction – perhaps 0.0001% – of global photosynthesis is diverted by burial in this way, and thus adds to atmospheric oxygen. But over millions of years, the residual oxygen left by this tiny imbalance between growth and decomposition has accumulated to form the reservoir of breathable oxygen on which all animal life depends. It has hovered around 21% of the volume of the atmosphere for millions of years.

Some of this oxygen returns to the planet’s surface through chemical reactions with metals, sulfur and other compounds in Earth’s crust. For example, when iron is exposed to air in the presence of water, it reacts with oxygen in the air to form iron oxide, a compound commonly known as rust. This process, which is called oxidation, helps regulate oxygen levels in the atmosphere.

Don’t hold your breath

Even though plant photosynthesis is ultimately responsible for breathable oxygen, only a vanishingly tiny fraction of that plant growth actually adds to the store of oxygen in the air. Even if all organic matter on Earth were burned at once, less than 1% of the world’s oxygen would be consumed.

In sum, Brazil’s reversal on protecting the Amazon does not meaningfully threaten atmospheric oxygen. Even a huge increase in forest fires would produce changes in oxygen that are difficult to measure. There’s enough oxygen in the air to last for millions of years, and the amount is set by geology rather than land use. The fact that this upsurge in deforestation threatens some of the most biodiverse and carbon-rich landscapes on Earth is reason enough to oppose it.

Scott Denning, Professor of Atmospheric Science, Colorado State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.