The time Japan’s bestselling author staged a coup and committed seppuku

- In 1970, the celebrated Japanese author Yukio Mishima committed suicide after a failed attempt to overthrow his government.

- Since that fateful day, scholars have studied Mishima’s fiction writing to better understand his behavior toward the end of his life.

- Mishima’s complicated sense of identity, paired with nostalgia for his childhood in prewar Japan, may have led him to change the course of history.

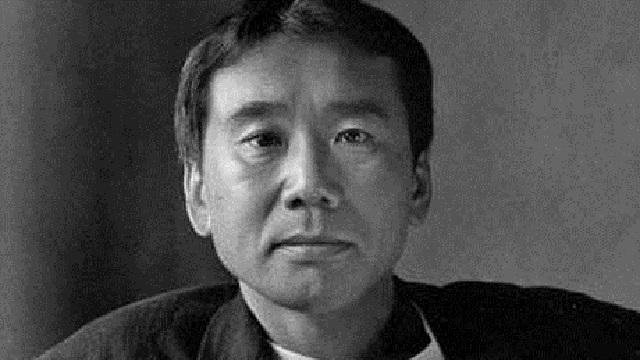

Before Haruki Murakami arrived on the scene, Japan had another renowned writer in the form of Yukio Mishima. Born in Tokyo in 1925, Mishima solidified his place in history with novels like The Temple of the Golden Pavilion and The Sound of Waves. He was one of the first Japanese authors to write a New York Times bestseller, and was nominated for the Nobel Prize in literature on three separate occasions.

Today, the literary accomplishments Mishima achieved throughout his life have become overshadowed by the absurd yet equally poetic circumstances of his death. On November 25, 1970, Mishima – aged 45 – drove to an army base outside of Tokyo intent on starting a revolution. After kidnapping the base’s commander, he tried to convince its soldiers to help him overthrow Japan’s Western-backed government and reinstate the emperor.

Mishima hoped the men would receive his impassioned speech – which he delivered standing from the top of a balcony clad in military uniform – with similar levels of enthusiasm. When they looked confused and apathetic instead, the author turned to an accomplice and said, “I don’t think they heard me.” He then went back inside and disemboweled himself with a samurai sword.

Mishima’s suicide and the events that led up to this dramatic act have, according to BBC journalist Thomas Graham, created “an enduring but troubling myth” around the author. While the author’s death helped propel him towards unprecedented levels of stardom, the controversial politics he worked into his fiction ended up tainting his legacy as a poet.

Yukio Mishima: his life and work

Over the years, many commentators have speculated as to what could have possibly driven Yukio Mishima to take his own life. In a 1975 article written for The New York Review, the Japanese philosopher Hide Ishiguro entertained the possibility that it was “a series of exhibitionistic acts, one more expression of the desire to shock for which he had become notorious.”

At first glance, this interpretation seemed rather convincing. Even in advancing age, Mishima was considered an enfant terrible. He had a strong sense of self-worth and, like Andy Warhol or Salvador Dalí, treated his public persona as a work of art in and of itself. His extremely successful debut novel, Confessions of a Mask, which tells the story of a young boy who – instead of playing outside with his neighbors, is forced to care for his terminally ill grandma – is believed to have been largely autobiographical, offering what Graham calls a “thinly veiled” reflection of his own life.

If the protagonist from Confessions is a parallel to Mishima himself, the novel can help us better understand the twisted psyche of its author. Spending most of his time with a person approaching the end of their life, Mishima became all too conscious of his own mortality. Stuck indoors with nothing but books and stories for company, he lost the ability to distinguish reality from fantasy, with the latter taking over as time went on. Unable to act like himself around his strict caretaker, Mishima developed a fascination with roleplaying, seeing life as one large theater.

Mishima’s fiction provides neither a thorough explanation nor justification for his destructive behavior. They can, however, establish important context. Mishima’s voice is sentimental and romantic, with aesthetics taking prevalence over all else. Mishima once said beautiful people ought to die young, and the author’s suicide can be understood as an attempt to confirm his own self-worth. “The self-transformation into a warrior had made him the object of his desire,” Graham wrote. His life was “something worth destroying.”

Stranger than fiction

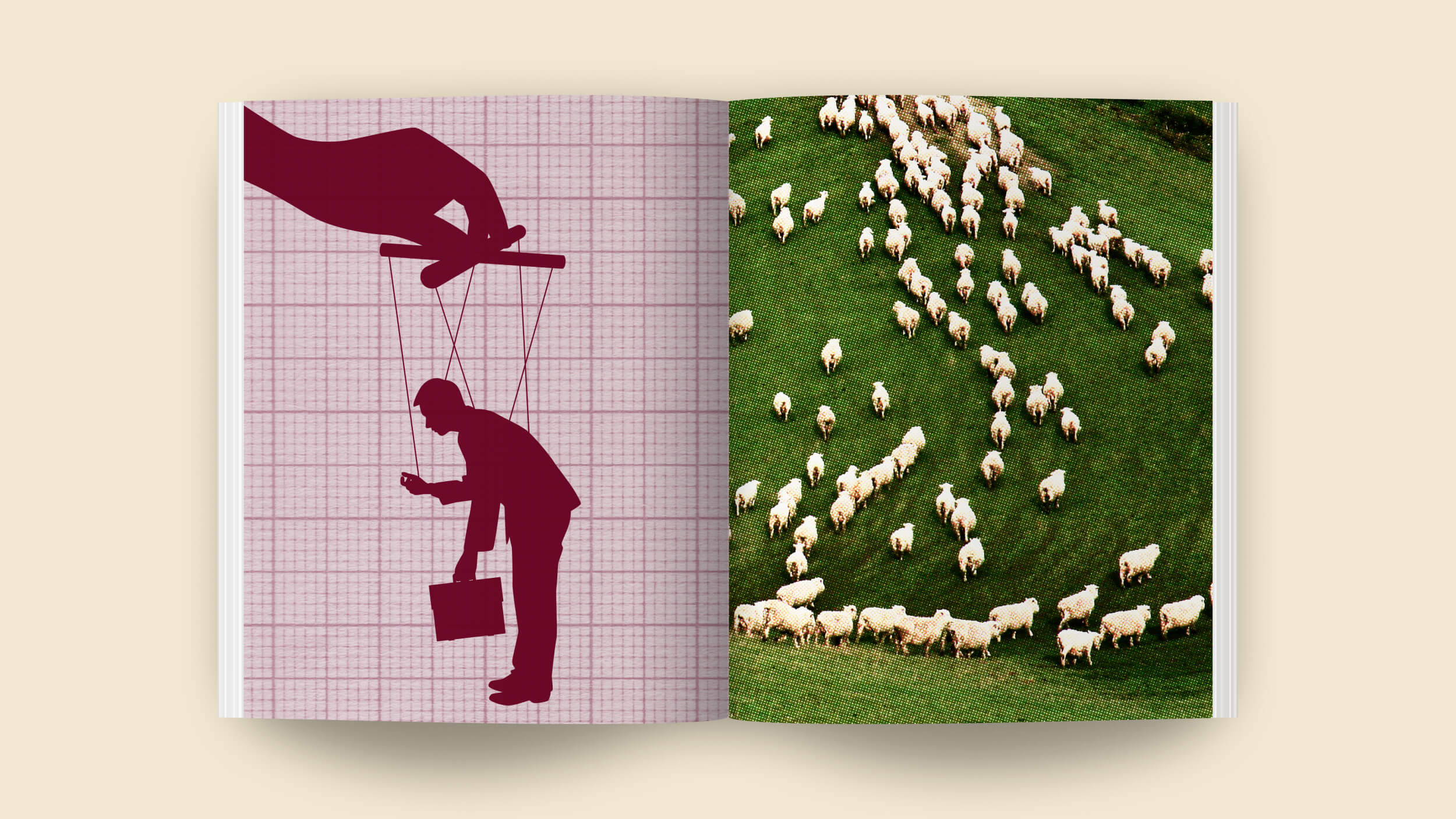

Others interpret Yukio Mishima’s ritual suicide not as the culminating battle in a war with his personal demons, but a response to the larger social, political, and religious developments that plagued Japan during his lifetime. Mishima romanticized his upbringing in the prewar era and his nostalgia resembled that of other people raised in totalitarian states. In a book review published in The New Yorker, Ligaya Mishan described him as raging “against the Emperor’s renunciation of divinity and the embrace of materialism by a once noble society dedicated to traditions of austere beauty.”

Although masculinity and self-assertion played important roles in Mishima’s fiction, the author’s obsession with prewar Japan did not stem from a desire to resume its imperialist conquest. Rather, Mishima yearned for this period because it marked the last time in modern Japanese history that people had been connected through a shared set of values and beliefs. An outcast from birth, Mishima desired unity above all else. This concept became personified by the emperor, whom he called “the symbolic moral source of loyalty and culture.”

If Mishima’s fiction represents one piece of this puzzle, the time in which he lived constitutes another. Life in Japan during the late 1960s was both similar and dissimilar to life in America. Young people were taking to the streets en masse, with their pro-war demonstrations frequently made the evening news. The cause of their anger was the Japanese Constitution of 1947, which removed emperor Hirohito from power, dismantled the country’s military, and handed over stewardship to the US.

When Japan surrendered to Allied forces at the tail end of World War II, they agreed to give up the right to declare transnational conflicts. Placed in a similar position as Germany following the end of the World War I, Japan’s university students demanded autonomy, including the right to involve themselves in the then-ongoing Vietnam War. They also craved national pride, which had evaporated when Mishima made his final stand; the blank stares he received from the military that day may well have served as the impetus for his suicide.

The final act

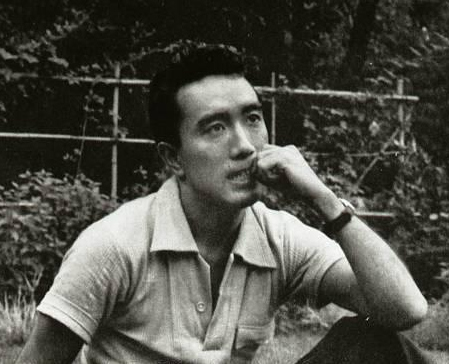

In the final decade of his life, Mishima’s obsession with his own image acquired a more noticeable political undertone. He began bronzing his skin and took up bodybuilding to compensate for his short stature, which had been a source of anxiety since puberty. The anti-communist militia organization that accompanied him during his final mission to the army base, known as the Tatenokai or “Shield Society,” started out as a workout club for right-leaning college students.

During this time, Mishima developed serious doubts about his writing career. His books, rather than allowing the author to influence the hearts and minds of his readers, instead enabled him to find refuge in his daydreams. “In the average person,” he wrote, “the body precedes language. In my case, words came first of all; then – belatedly – came the flesh.”

Put differently, Mishima felt that writing had alienated him from the physical world. Only by uniting the author’s pen with the blade of the samurai of old could he become the “man of action” he’d always wished to be.

Yukio Mishima’s suicide was not taken out of desperation when his plans went awry. Some believe it was planned from the beginning, a reliable backup plan that allowed him to leave a lasting impact in case his plan for revolution failed to come to fruition. In a way, Mishima’s attempt to revive the past succeeded. After all, no Japanese celebrity or statesman had died by seppuku since the war.