The love of art drove a man to steal. Is this a real mental illness?

- Stendhal syndrome was coined by Italian psychiatrist Graziella Magherini to describe patients who became sick when overwhelmed by art.

- Prolific art thief Stéphane Breitwieser has claimed Stendhal syndrome as an explanation for his exploits. But his detractors call him a glorified shoplifter.

- After meeting with Breitwieser, psychotherapist Michel Schmidt excluded a diagnosis of kleptomania.

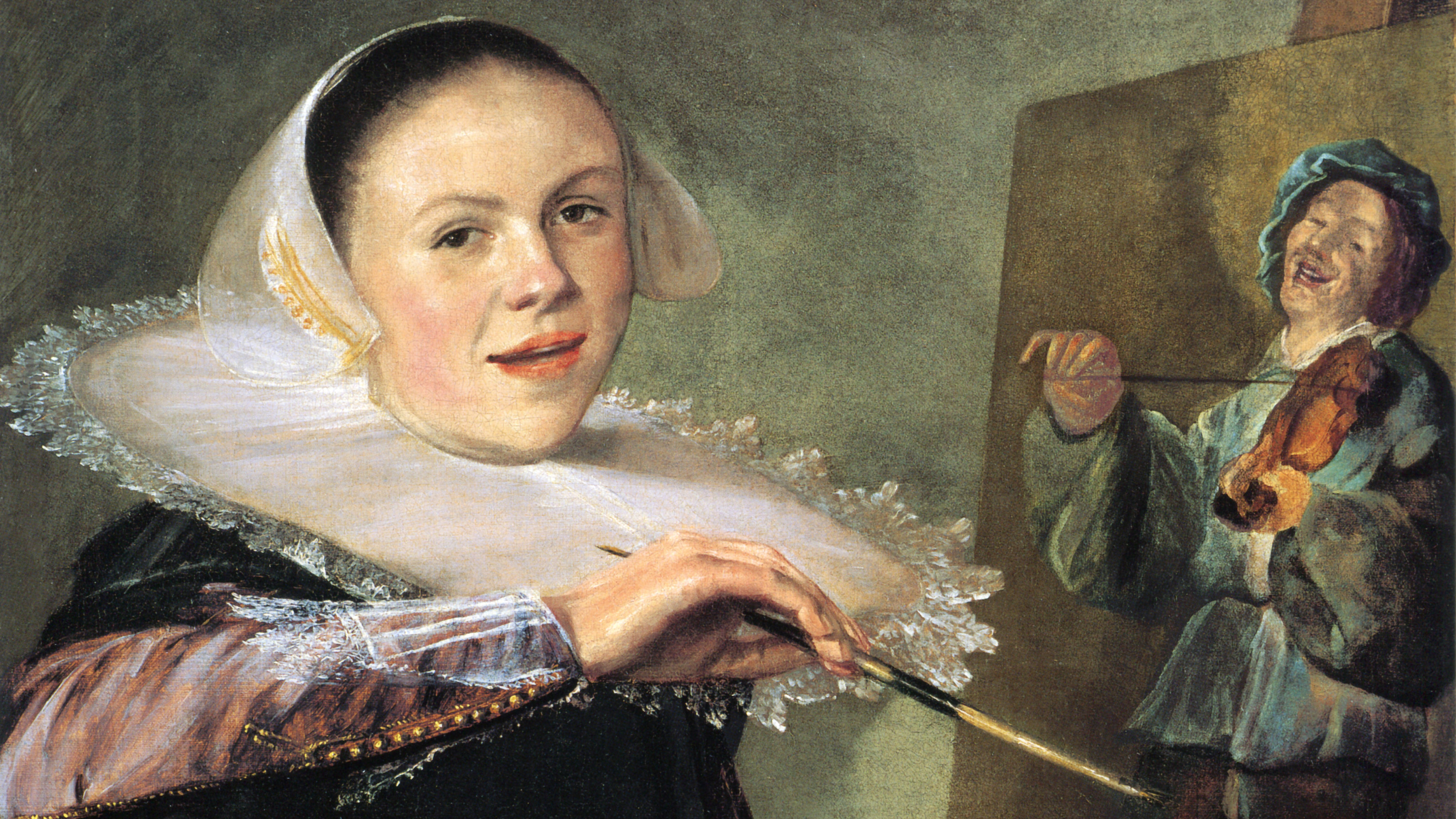

The French writer Stendhal, in his 1817 travelogue, Rome, Naples, and Florence, described an incident that took place in Florence’s Santa Croce basilica. Inside a small chapel tucked within the vast church, Stendhal tipped his head back to absorb the vaulted ceiling’s spectacular frescoes. He was overcome, he wrote, with “celestial sensations” and “impassioned sensuality” and “the profoundest experience of ecstasy.” Fearing that his heart might burst, Stendhal fled the chapel, stumbling and faint, and sprawled on a bench outside and soon recovered.

In the 1970s, Graziella Magherini, the chief of psychiatry at Florence’s central hospital, began documenting instances of visitors who had become overwhelmed by art. Symptoms included dizziness, heart palpitations, and memory loss. One person said she felt as if her eyeballs had grown fingertips. Michelangelo’s iconic sculpture of David was one of the more common triggers. The effects lasted from a few minutes to a couple of hours. Magherini advised bed rest and sometimes administered sedatives. The patients were all cured after staying away from art for a while.

Magherini compiled more than 100 cases, divided evenly among men and women, most between the ages of 25 and 40. Those who experienced the sensation were prone to repeat occurrences in front of other artworks. Magherini published a book on the disorder and gave it a name: Stendhal syndrome. The condition has since been widely reported; Jerusalem and Paris seem to be hot spots. But outside Florence the information is only anecdotal, and the condition remains an unofficial one, not listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

Art thief Stéphane Breitwieser says that when he learned of Stendhal syndrome, he felt a shock of recognition. Here, documented by a doctor, seemed to be a description of his coup de coeur. He was grateful to discover that he wasn’t alone, slightly less alienated from the human race.

Breitwieser does not react to every artwork, not nearly, but when he is transported, the response is instinctual and rapid and often hypnotically strong. “Art is my drug,” he declares. Breitwieser says he is puritanical about actual drugs: no tobacco or caffeine, no alcohol except a sip of wine when politeness requires, and never marijuana or anything harder. But a pure dose of art can set his head spinning.

When asked about Breitwieser’s claims of Stendhal syndrome and art as a drug, many people in the art world, as well as most police inspectors, say he’s lying. Stendhal syndrome, some argue, is merely a fancy name for jet lag or heat exhaustion. What Breitwieser is really addicted to, his detractors say, is stealing. He’s a glorified shoplifter; he’s a kleptomaniac.

Breitwieser furiously denies this. He does not enjoy his thefts, he insists. He cherishes only the results. His compulsion is collecting, not stealing. Weighing in on what kind of thief he might be is the Swiss psychotherapist Michel Schmidt, who visited with Breitwieser several times in 2002 and issued a 34-page assessment. Breitwieser is clearly a menace to society, Schmidt says, and self-deluded by thinking that his crimes are in any way justifiable. But nothing in the therapist’s report supports the idea that Breitwieser is a pathological liar or a compulsive thief.

The psychotherapist believes that Breitwieser truly steals for the love of art.

A kleptomaniac, Schmidt cautions, does not care about the specific objects stolen, just the act of stealing itself. Also, a theft by a kleptomaniac is typically followed by a letdown steeped in shame and regret. Breitwieser is the opposite. He is selective about his loot and exults in his criminal success. “I exclude a diagnosis of kleptomania,” Schmidt states. The psychotherapist believes that Breitwieser truly steals for the love of art.

Breitwieser’s blind spot is for perceiving how others see him. The only reason he’s considered a common thief rather than appreciated as a special case, Breitwieser says, is that the police and psychologists, along with most everyone in the art world, are aesthetically impotent. They’re incapable of comprehending the potency of a Stendhal reaction, and this frustrates him. He knows how he feels, but how can he prove it?

In the turret of Gruyères Castle, gazing at a small oil portrait of an elderly woman by 18th-century German realist Christian Wilhelm Ernst Dietrich, he describes himself as “stunned and amazed.” He stares at it for ten minutes, unable to move. After that he knows what to do. Security cameras have not been installed in the turret; Breitwieser is often pleasantly surprised that regional museums are sparsely protected. No guards or visitors are near. He pulls his gaze from the portrait and glances at his girlfriend Anne-Catherine Kleinklaus. She certainly likes the style of art preferred by Breitwieser, but not in an intense, Stendhal syndrome sort of way. She seems to have a greater attachment to her boyfriend. Anne-Catherine responds to his look with one of her own, signaling consent.

He tugs down the picture and extracts the four thin nails on the back that attach the painting to the frame. For this task, he uses the edge of his car key — a secondary, unofficial tool, supplementing his Swiss Army knife. He stashes the frame higher up in the turret, and pockets the wall label. There’s nothing he can do to hide the clean spot, the size of a pizza box, now imprinting the wall.

Breitwieser and Anne-Catherine walk out of the castle together, his jacket covering the work — their third theft as a couple, and their first painting. They endure the long walk through the medieval village of Gruyères, to the car park. They cushion the piece in a suitcase and drive off, only to pull over later and admire the portrait more. Then they head to the ski slopes.