How to write like Ernest Hemingway

- Ernest Hemingway owes his signature writing style to his time at The Kansas City Star.

- Like that of a reporter, Hemingway’s writing was always clear and concise, imparting crucial information without literary flair.

- A man-of-action, Hemingway drew inspiration from life rather than imagination, waging wars and traveling the globe in search of stories.

Today, more than 60 years after his death, Ernest Hemingway is known not just for his moving stories but his technical writing skills. According to E.J. Gleason, professor of Irish and American literature at Saint Anselm College in New Hampshire, Hemingway had found his artistic voice before he turned 26. His signature writing style, characterized by short phrases constructed using plain, everyday English, left a profound impact on the literary world, shaping generations of aspiring fiction and non-fiction writers that followed in his footsteps.

Although Hemingway’s way of writing may seem straightforward, it is by no means simplistic, let alone easy to imitate. A less talented writer might hide their lack of substance behind difficult words and convoluted sentences, but to write like Hemingway requires both a great effort and real intellect. Like a surgeon, Hemingway stripped his stories of any and all insignificant or superfluous information, until only a basic skeleton and a handful of vital organs were left on the page.

Hemingway’s writing skills caused the popularity of his novellas to skyrocket, and his ability to express himself efficiently allowed him to establish powerful — albeit slightly volatile — relationships with others. Difficult though these skills might be to acquire, it can be done. In his 2019 book, aptly titled Write Like Hemingway, Gleason outlines 10 rules the author set for himself. Will following these rules result in you penning the spiritual successor to The Old Man and the Sea or A Farewell to Arms? Probably not, but it will make the quality of your writing closer to that of Hemingway’s.

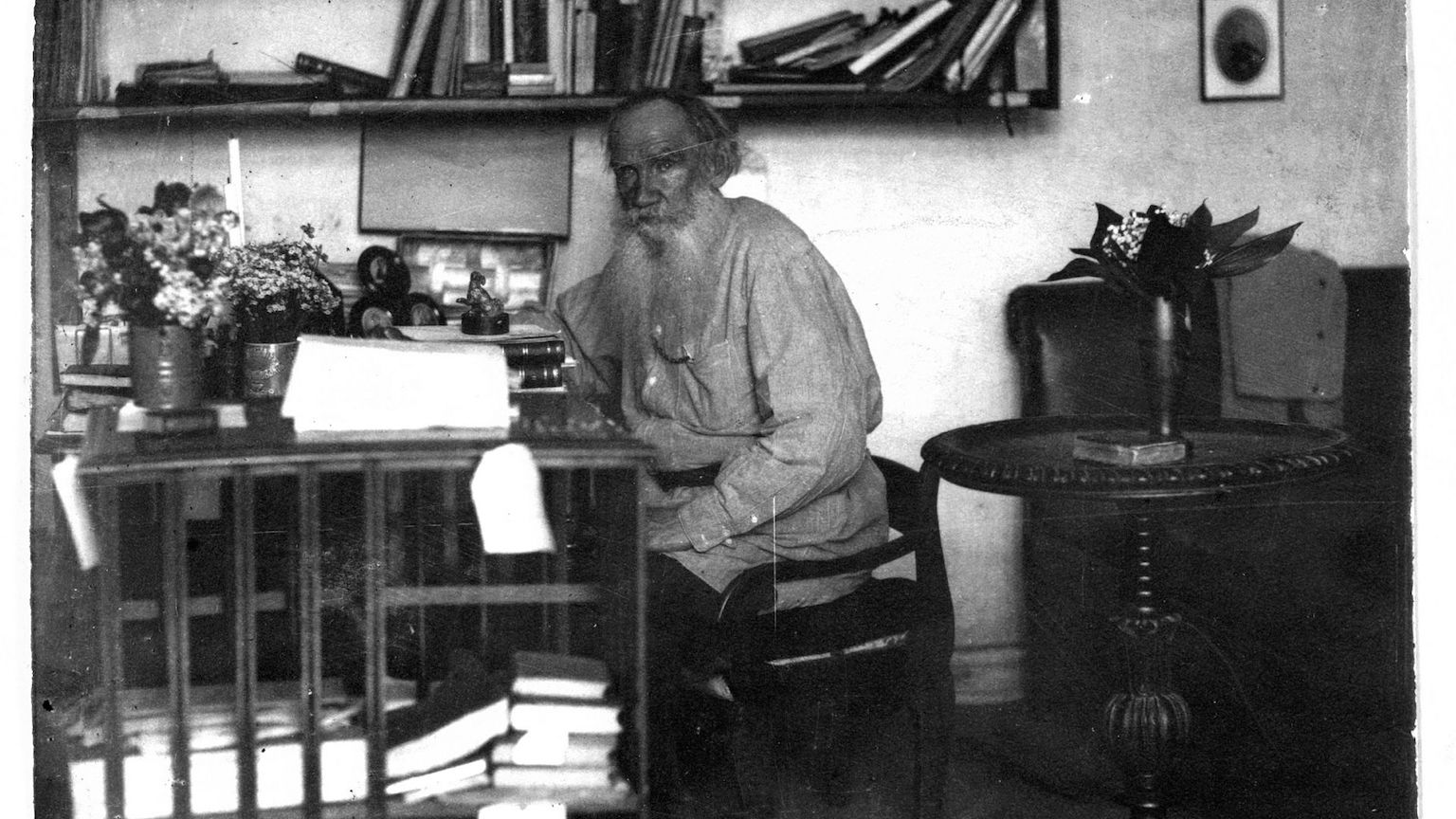

The Kansas Star style guide

Gleason, who studied and taught Hemingway many times during the 50 years he spent in academia, traces the origins of Hemingway’s writing style back to his first job as a reporter for The Kansas City Star. Using family connections, Hemingway began working for the paper right after he finished high school. Though he was happy to have left the sterile classroom setting behind, he still worried that his unrefined grasp of spelling and grammar could hurt the quality of his reporting. Fortunately, the editors at the paper were more than ready to give him a crash course.

The Kansas City Star owes much of its existence to one editor in particular, Thomas W. Johnston, Jr., who turned it from a local into a state-wide paper, replete with half a million readers. Johnston left the Star a year before Hemingway came aboard but still played a key role in developing the young man’s talents. Johnston offered his colleagues considerable autonomy when reporting, as long as their reports were rendered in technically sound English. He compiled his linguistic judgments into a style guide, and Hemingway — like all Star staffers — treated this guide as though it was scripture.

Every rule in Gleason’s book is tied to a section from this guide. These include, “Use short sentences,” and, “Be positive, not negative.” The guide not only covers concrete issues such as punctuation and grammar but also more abstract concepts like tone, voice, and point of view. While writers such as William Faulkner or James Joyce liked to experiment with their language, Hemingway was more conservative. “Style,” Gleason wrote of the author’s lifelong conviction, “is not the product of conscious choice, but of consistently working hard at one’s craft.”

From reporter to writer

There is a good reason why many of the world’s greatest storytellers have backgrounds in journalism: because journalists know better than anyone how the way in which a story is written affects its telling. The reporter possesses several skills that give him a head start over the fiction writer, especially when it comes to editing. While authors use as many pages as they want, a reporter must stay within his allotted word count. Printing space is limited, and if something important happens, readers want quick facts, not literary flair.

To meet these requirements, reporters try to write as economically as possible. Long sentences are to be avoided like the plague, and everyday vocabulary always takes precedence over occupational jargon. “Both simplicity and good taste,” states the style guide of the Star, “suggest home rather than residence and lives rather than resides.” Hemingway’s rigorous editing, rather than robbing his writing of its complexity, added depth. By removing unnecessary details like scene descriptions or adjectives, the author is able to tell his story as efficiently as possible.

Many great writers are also good editors. Thomas Mann typically wrote around 5,000 words per day, which he then narrowed down to about 500. However, few authors knew how to use the absence of information quite like Hemingway. His matter-of-fact voice and bare-bones descriptions make the rape scene at the end of “Up in Michigan” even more chilling. The author frequently likened his writing to an iceberg — what’s on the page is just a small part of the narrative. The rest of it is hidden in between the lines, discoverable via induction and inference.

Into the trenches

Of course, novels and news articles are two completely different things. One is meant only to inform; the other to inspire and entertain. Consequently, there are more than a couple of writing techniques that, while they work wonders for the reporter, are of little use to an author. Detailed descriptions and literary devices like metaphors do not belong in the paper, but in novels they can provide context and — most importantly — set the mood. “Get the weather in your… book,” John Dos Passos begged a still young Hemingway, whose premature writings were so simplistically worded, they risked losing all sense of character.

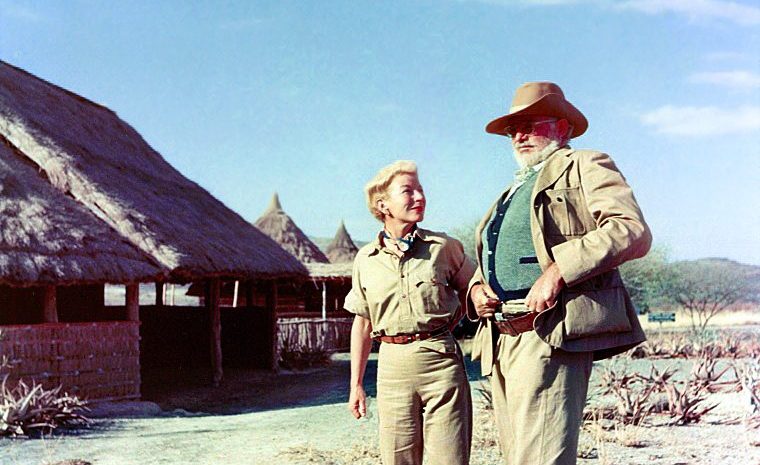

Hemingway paid his critics little mind. After learning style from the Star, he set his eyes on the second ingredient for storytelling: substance. A self-proclaimed man-of-action, Hemingway preferred drawing inspiration from real life rather than fantasy. When the First World War broke out, Hemingway left Kansas to become an ambulance driver for the Red Cross. Placing himself “in the path of harm so that he could cull experiential material for his fiction,” he drove around Europe saving wounded soldiers before getting badly injured himself.

Almost everything Hemingway experienced during the war worked its way into his fiction one way or another, especially in his book A Farewell to Arms. As Gleason points out, there is not a single character in The Sun Also Rises that isn’t based on someone Hemingway knew. The author’s insistence on pulling from reality made his business partners nervous. In 1953, the author sent a letter to his lawyer, Alfred Rice, saying “most of the people” in the stories he was working on were “alive” and that he was “writing it very carefully not to have anybody identifiable.”

Writing like Ernest Hemingway

Like any other self-scrutinizing writer, Hemingway frequently fell prey to writer’s block. But unlike other writers, Hemingway rarely let his creative stagnation bother him. He was a heavy drinker, but he never drank when writing. Whenever he became stuck on a project, he would stand in front of his windows and look out over the skyline. “All you have to do,” he explains in his memoir, A Moveable Feast, “is write one true sentence. Write the truest sentence that you know. There was always one true sentence that I knew or had seen or had heard someone say.”

Hemingway’s technical writing abilities produced some of the most beloved entries in the Western literary canon. “To test the integrity of any book,” Gleason concludes, “aspiring novelists might ask: what chapter, passage, character, or subplot could be eliminated from — or elaborated upon — that would result in a more effective product?” When it comes to Hemingway’s best work, the answer is a resounding, “Nothing.” Every scene, phrase, and word serve at least one purpose. Even if that purpose isn’t clear from the beginning, it will certainly be revealed before the end.

Ernest Hemingway is the type of author whose writing is familiar even to those who do not typically read Literature with a capital L. His stories are assigned in almost every American high school, where they are received positively by students. This is because Hemingway had a knack for capturing the interest of even the most absent-minded readers, whom he draws in with the brevity of his texts and keeps engaged by using a prose so clear, so accessible, it makes you wonder why none of the other so-called literary classics weren’t written the same way.