The dangers of keeping epidemiology the “hidden science”

- Caitlin Rivers, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, calls epidemiology the “hidden science” because while its successes helped shape the modern world, they are also overlooked.

- This invisibility feeds a cycle of panic and neglect that undermines our preparedness for future outbreaks.

- Sustained investment and awareness of public health may better equip us for the next outbreak while also helping us live healthier lives.

In February 2003, Carlo Urbani encountered a mysterious virus in Vietnam. A physician-epidemiologist well-regarded for his diagnostic skills, Urbani was asked to come to the French Hospital of Hanoi to see a patient named Jonny Chen, an American businessman who had grown seriously ill after a recent trip to Hong Kong. His doctors feared he may have contracted avian influenza — which, while rare in humans, has the potential to trigger the next flu pandemic — and they wanted Urbani’s expert opinion.

After examining Chen, Urbani grew worried. The patient’s decline had been rapid and severe for someone as young and, until then, healthy as him. Additionally, 12 healthcare workers who had contact with Chen fell ill. Given that healthcare workers take strict precautions to prevent contracting diseases from patients, Urbani feared the worst: a new disease that was not only deadly but also highly infectious. He contacted several colleagues and learned about an outbreak of pneumonia spreading through Guangdong, a Chinese province bordering Hong Kong to the north.

That proved enough for Urbani. He and his team alerted international public health officials over their concerns.

Ultimately, it wasn’t an avian flu virus but a novel coronavirus that afflicted Chen — one known today as SARS-CoV-1, or simply SARS. Nor was Chen patient zero, as the first known case would eventually be traced back to Guangdong. It was, however, Urbani’s warning that triggered the World Health Organization (WHO) to forewarn public health officials worldwide to search for similar cases in their regions. Those early efforts to identify and isolate infected people allowed the world to restrain the virus’s spread, likely preventing the outbreak from blooming into an unruly pandemic.

As Caitlin Rivers, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security who specializes in epidemic preparedness, writes, “When I think about the phase of an outbreak and the race to gain the upper hand, so much hinges on the skills of the experts rushing to respond. At each phase, there are skills both learned and intuited that spell the difference between success — bringing the outbreak under control — and failure.”

Rivers shares Urbani’s story, and the stories of many other researchers, in her new book Crisis Averted to shine a light on what she calls “the hidden science” of epidemiology. Why hidden? Because the more epidemiology succeeds, the less we have to think about. Unlike our ancestors, most people today don’t have to fret over whether their water is safe to drink, their hospitals are sanitized, or that case of flu going around will decimate their community. We simply accept these favorable conditions will persist and go about our lives.

That’s by design, but epidemiology’s hidden nature has a downside. It can inadvertently lead us to overlook the field’s importance in keeping us safe and healthy — which may undermine our preparedness for future outbreaks.

A cycle of panic and neglect

Epidemiology has come a long way since the ancient Greek beliefs that illnesses stem from an imbalance of bodily fluids or that contagions circulate on currents of poisonous air. In only the last few centuries has science managed to amass the empirical knowledge to capably contain outbreaks, thanks to forerunners like Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, John Snow, and Florence Nightingale. The “boots on the ground” techniques they helped establish — identifying microbes, isolating the sick, and sanitizing every surface in hospitals — remain vital in breaking the viral chains of transmission.

The tremendous efforts of public health workers ever since have allowed the modern world to bring to heel diseases that were historically perilous — even genocidal for some Indigenous peoples. Smallpox and rinderpest have been eradicated. Polio, mumps, measles, and rubella have been eliminated from many societies and may be eradicated one day. Vaccines alone have saved an estimated 150 million children’s lives in the last half-century, while diagnostic testing, treatments, and preventative medicine have saved countless more.

As this short history suggests, the story of epidemiology is a remarkable tale of human ingenuity and cooperation, but one largely untold and seldom uncelebrated. One reason is that epidemiology’s victories don’t make for the best photo ops. Viruses don’t surrender and sign treaties of non-infection. There are no parades on Main Street when the doctors come home. Instead, progress is made person by person, and day by day, the disease quietly retreats. And our minds turn to other, more immediate matters.

For reasons like this, Rivers refers to epidemiology as medicine’s “quiet cousin.”

“Historically, it’s been hard for us to make the case about why the work we do is so important and valuable,” Rivers told Big Think. “COVID-19 did elevate what can happen when things go wrong and when Mother Nature challenges us. But many success stories throughout history haven’t gotten the attention they deserve because epidemiologists pulled us back from a very scary situation.”

This invisibility leads to what Rivers calls the cycle of panic and neglect. An outbreak, pandemic, or other public health crisis rears up and jolts us out of complacency. Urgency builds, media outlets offer breathless coverage, and the pressure to respond pushes government officials to action. Downstream, public health officials receive a boost of attention, support, and funds to tackle the problem, which they often do.

“Progress, though, is not triumph,” Rivers writes. As case numbers fade and transmission rates fall, the urgency lapses in kind. Funding and support dim, and we return to complacency until the cycle starts again with the next crisis.

This cycle may even be playing out with the all-too-recent COVID-19 pandemic. While we are passed peak COVID, the disease hasn’t gone anywhere. Countries continue to report cases and deaths, and for the immunocompromised, the virus remains an ever-present danger. Yet, despite how fresh the memories of 2020 remain, the signs of complacency are present.

For instance, according to the CDC, only around 11% of children, 22% of adults, and 44% of the 65-plus crowd have reported receiving the most recent COVID-19 vaccine. While those numbers may climb as the winter season advances, they are well below the percentage of Americans who report getting the most up-to-date flu vaccine. And 40% of Americans report they likely won’t get this year’s COVID vaccine at all — despite evidence showing that vaccines, while not perfect, ease the severity of the illness and reduce the chance of passing it to others, thereby improving herd protection.

“The last respiratory pandemic was in 1918, so we think of it as an every hundred years event, but Mother Nature’s not on a schedule,” Rivers says. “I worry that it’s going to be all too easy — or maybe we’re already starting — to fall back into the neglect cycle and move on without absorbing the lessons of what we all experienced.”

Can we break the cycle?

Breaking this cycle wouldn’t render our societies impervious to the next outbreak. Natural selection ensures novel viruses will continue to evolve and that we’ll be susceptible — if not to the next one then one further down the adaptation line. Doing so would, however, be an important step in helping us better prepare for that inevitable event and hopefully strengthen the safeguards that allow us to detect and respond to diseases quickly.

Unfortunately, several barriers stand in our way, one of which is simply our mental makeup. Evolution wired us to pay attention to the immediate and harmful. An outbreak happening right now in our neighborhood? That demands our attention. One that may occur decades from now halfway across the world? Worth considering, but life overcrowds with more pressing concerns. That’s not to say we never plan for the future — public health’s ability to respond to SARS proves otherwise — just that it’s not always our forte.

Consider your personal habits and behaviors. We understand that eating healthier, sticking with an exercise routine, and staying home when we’re sick today confer long-term benefits later, but we also know the difficulties of sticking with these habits. And even if we do stick with them, we all feel the ever-present draw of complacency. As life and family responsibilities pile up, it becomes easy to skip the morning run or head to the office with a barking cough. Immediate concerns take priority over our future health.

Public health officials deal with this problem at scale. They have to inform citizens of the science so they can make informed decisions about their behaviors while also steering entire communities to remedy potential health risks before they become tangible emergencies. Unfortunately, Rivers cites research in her book showing that such interventions typically produce modest returns.

The problem is compounded by the matter of communication. Science is nuanced. New evidence often complicates established research findings, experts disagree over what lessons to draw from the evidence, and news outlets favor eye-catching studies over rigorous methodology. Finding a message that is concise, accurate, and leads to the desired action is no easy task. Oversimply too much, like in the 1990s “Just Say No to Drugs” campaign, and people feel talked down to. Fail at offering a coherent message, and they get confused — as we saw during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic when expert advice seemed to shift daily.

“[Today’s] fractured landscape has made it even more difficult to know how to reach different segments of the population,” Rivers points out. “The only thing we can do is accept that it’s going to require many more touch points to reach different segments of the population.”

That’s not to say public health hasn’t managed some landmark successes. The campaign to stop smoking, a leading cause of preventable diseases, proved a massive achievement. Today, only 12% of US adults have taken up the habit, compared to 42% of their 1965 peers. That trend line is even steeper among young people, and second-hand smoke has cleared out of public places such as restaurants and airplanes.

“Tobacco cessation is a strong example of sustained efforts to build the science and the evidence base for why a behavior is unhealthy,” Rivers says. “But that is one success story in a field of stories that are not quite as successful. It’s still an open question, I think, of how to do it successfully.”

Revealing the hidden science

One of Rivers’s projects — both in her book and her other writings — is to share the story of epidemiology. She wants to not only tell the incredible tales of people like Urbani, but also remind us to remember and share our own. After all, we lived through the COVID-19 pandemic and experienced it in different ways. While that year was certainly demanding, and for many tragic, being more open about those experiences and struggles may help us avoid another lapse into complacency.

“I believe in the power of stories to help us understand the world,” Rivers says. “Storytelling has been a major part of military history and even the medical field in ways that have not been true of public health. Part of what I wanted to do in the book is tell [those] stories to help readers understand how gripping the history of public health can be and, maybe through them, start to appreciate what public health has done for us.”

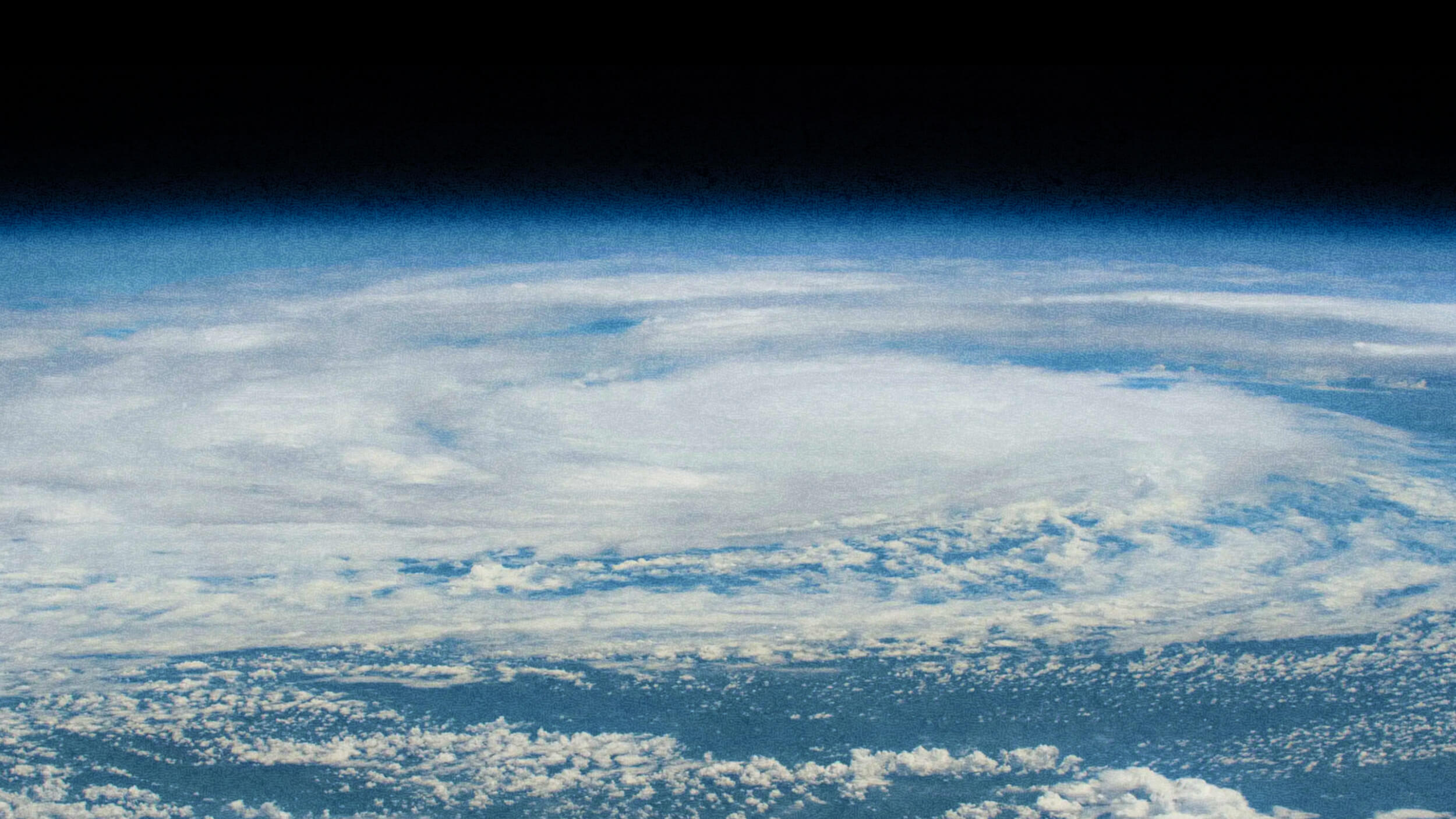

Rivers also thinks our news media needs to report on public health more like the weather. Meteorologists aren’t spotlighted only when they need to warn us to batten down the hatches. They provide daily updates to help us understand how the weather will affect our days and communities — whether that’s a warning about an incoming hurricane or a gentle reminder to carry an umbrella.

News media could do a better job of regularly informing citizens of what diseases are currently in their area and what precautions they should take. The goal is to normalize public health to become a small piece of everyday upkeep, so we’re better prepared when the larger events happen.

“I think another latent assumption about public health communications is that it always has to be alarming,” Rivers says. “It’s also okay to say things are looking great right now. That can be useful information, as well.”

Stories of triumph and tragedy

Urbani’s personal story sadly ended soon after his discovery. He contracted SARS and died on March 29, 2003. He was 46 years old.

Thanks to his selfless efforts, public health officials broke the SARS chain of transmission early and, in doing so, saved an untold number of lives. All told, the disease claimed the lives of 774 of the roughly 8,000 worldwide cases, but that number represents a fatality rate of 9.6%. For comparison, COVID’s fatality rate was about 1%.

“To stop it in its tracks, this virus had to be chased to the ends of the earth — person by person by person,” Rivers recounts. “If epidemiologists had lost control of that outbreak, it could have been horrifying. Even the situation as it played out was certainly a great tragedy, but the thing with outbreaks is that they grow until you stop them. We came very close to being in a much worse position.”

Urbani’s story reminds us what we gain from epidemiology and how people on the frontlines of this hidden science keep the modern world safe and healthy.

As Rivers writes: “We are never more than one laboratory accident, one virus spilled over from animals, one contaminated consumer product away from disaster. I offer that observation not to startle, but to reinforce that the work cannot be taken for granted for even one second. Only with great effort does public health maintain an invisible veil between us and a world I don’t want to see return.”