SIDS: Uncovering the mystery of sudden infant death

- Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) continues to kill thousands of infants a year.

- Researchers have identified risk factors, but the exact cause of this all-too-frequent tragedy remains elusive.

- A recent review of the research suggests that under-investigated findings, such as respiratory infection, may hold the key to solving the SIDS mystery.

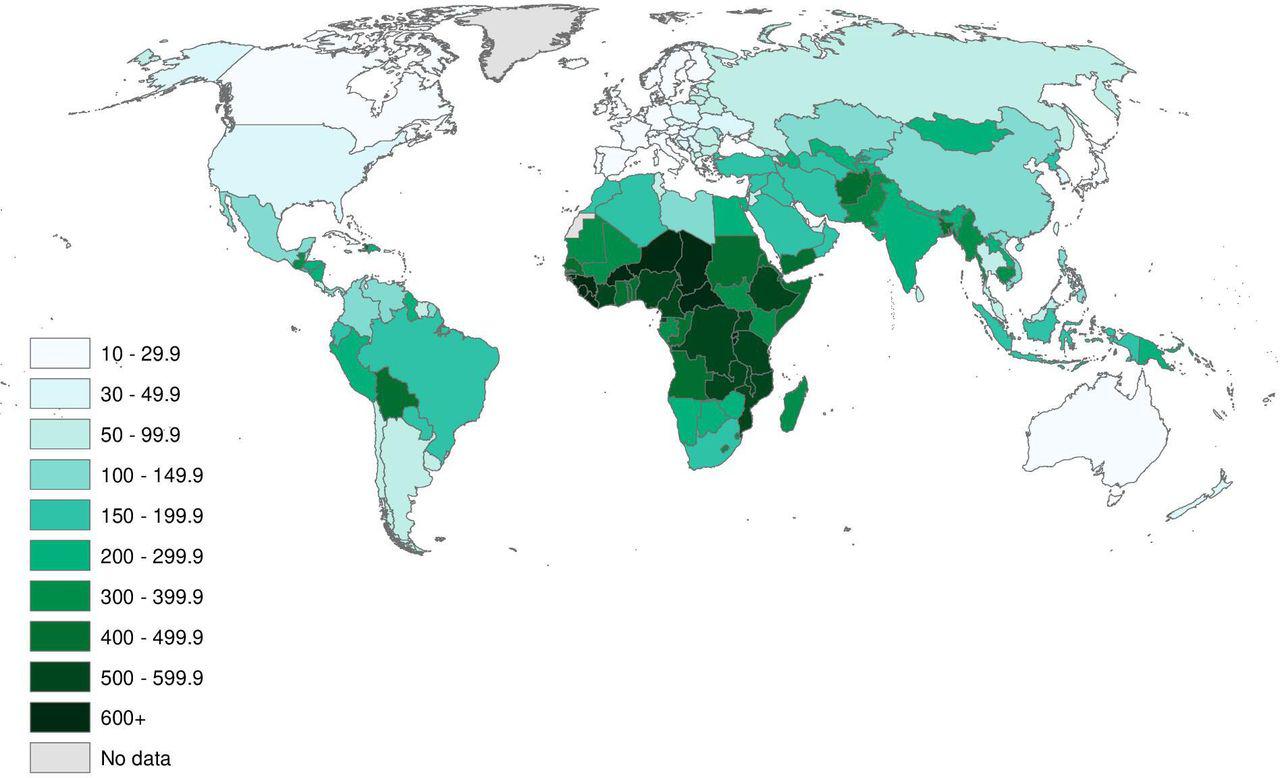

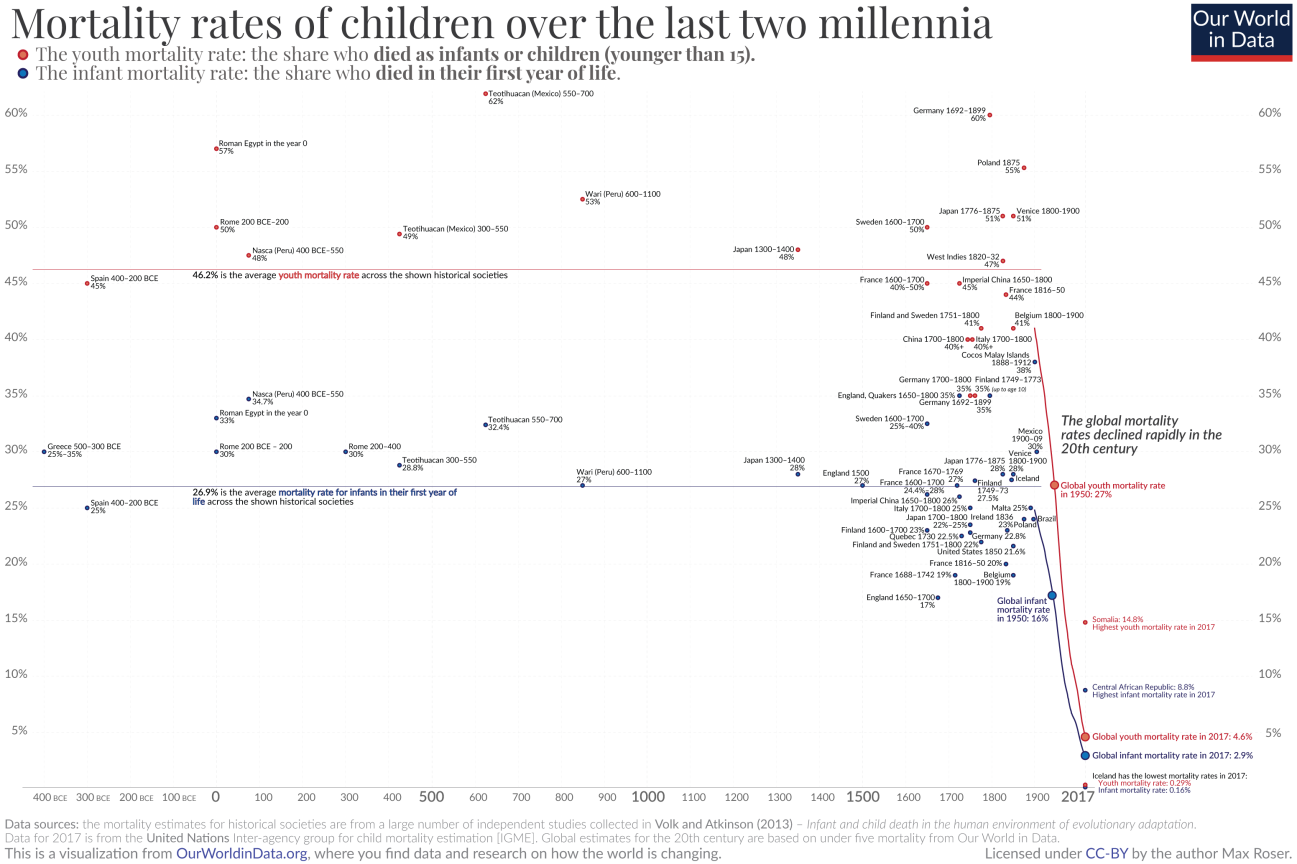

Losing a child is the nightmare of every parent. But while this tragedy continues with alarming regularity, child mortality rates thankfully have declined compared to ghastly historical norms.

This success is largely due to science and medicine, which have granted us the knowledge to understand childhood diseases and the tools to develop a means to treat, if not outright prevent, them. Modern technology and industry have in turn allowed us to scale these treatments globally. All told, between 1950 and 2015, child deaths have declined five-fold across the world.

Yet science remains in the dark concerning one frightful cause of childhood mortality: sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS).

The scene is as somber as it is sudden. Parents put a seemingly healthy infant to bed at night. By morning, the child has passed away. The reason is unknown, and follow-up investigations seldom provide definitive answers. And in 2019, this nightmare was endured by more than 27,000 families globally.

SIDS is in decline, but not gone

That’s not to say progress has been at a standstill. In 1990, nearly 56,000 infants died of SIDS worldwide, meaning there has been a 50% decline in just 30 years. Some countries have seen even better results. The U.S. saw SIDS cases fall by 75% between 1990 and 2019. In Australia, they fell by 85%. Those numbers represent thousands of families who haven’t had to suffer the horror of SIDS.

It’s an accomplishment worth celebrating, and this remedy came about thanks to the tireless efforts of many people. First are the researchers who worked hard to better understand the risk factors associated with SIDS, such as letting babies sleep on their stomachs, babies sharing a bed with others, or smoking in the home. Then there are the pediatricians, civil servants, and volunteers who conveyed that information to parents through public campaigns, like Back to Sleep in the 90s.

But while we know how to reduce the likelihood of SIDS, we still don’t know what causes it. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 28% of sudden unexpected infant deaths — an umbrella term that covers all unexpected infant deaths — are caused by accidental suffocation in the crib. The remaining 72% are considered to result from SIDS or an unknown cause — in effect, two different ways of saying: “We don’t know why this child died.”

SIDS research appears to have lost its way.

– Paul Goldwater

A triple threat

In a recent paper published in Frontiers in Pediatrics, Paul Goldwater, a senior researcher at the University of Adelaide’s Medical School, surveyed the current research from leading peer-reviewed publications. A researcher of SIDS for the past 30 years and someone who has published on the subject himself, Goldwater’s conclusions were stark.

“SIDS research appears to have lost its way,” he wrote. “Mainstream findings are often based on questionable and dogmatic assumptions that return to founding notions such as the Triple Risk Hypothesis and the contention that the mechanisms underlying SIDS/SUID are heterogeneous in nature.”

The triple risk hypothesis states that SIDS is likely caused when three factors overlap in a child’s development. These three factors are (1) vulnerability from an underlying susceptibility (e.g., prematurity or brainstem abnormalities); (2) a critical developmental period (e.g., between 2-4 months old); and (3) and external stressor (e.g., overheating or infection).

But research into this hypothesis, Goldwater points out, has not been fruitful. Despite “concerted efforts,” it has provided no answer to the cause of SIDS because it only helps us conceptualize it, not understand it.

Could an infection cause SIDS?

This is a problem, Goldwater explains, because a focus on the triple risk hypothesis has led researchers to sideline other avenues of research or ignore otherwise promising evidence. For example, his paper cites multiple studies that found “more than 75% of SIDS babies featured recent or active respiratory tract infections.” The findings of the autopsy reports are also consistent with infection and include fluid-laden lungs, inflammation, raised temperature, and liquid blood in the chambers of the heart.

“Despite these clues, infection and sepsis have not been widely examined in relation to most aspects of SIDS research and despite the findings of those proposing the Infection Model of SIDS,” Goldwater writes.

This could explain why campaigns for supine sleeping have reduced SIDS deaths since the 90s even if we didn’t understand the cause. It’s not that lying prone triggers sudden infant death. Some SIDS cases occur in supine and side-sleeping babies. But as one Nordic study found, an upper respiratory or other viral illness increases the chance of SIDS dramatically when combined with risk factors such as prone sleeping.

Goldwater calls this “prone-plus-infection” model a “nearly two-decade blind spot that may have kept a solution to the SIDS problem in the dark.”

Solving the SIDS mystery

Is Goldwater claiming infection to be the smoking gun? Not at all. Many questions remain to be answered. These include why SIDS occurs more often in baby boys and certain ethnicities, such as American Indians and Australian Aborigines. Genetics or socioeconomic factors may be partially to blame.

Rather, his stated hope is to highlight these neglected areas of research and reinvigorate fresh thinking in the area of SIDS research. “It is concerning that twenty-first century medical science has not provided an answer to the tragic enigma of SIDS,” he writes.

And if we can reduce the impact of SIDS as we have with our limited knowledge, imagine what we could do if we finally solved this modern-day medical mystery.