“Artificial nose” can smell when a person is about to have a seizure

Dogs have extraordinary noses. They can smell explosives and accelerants for arson, and the tiniest traces of narcotics, no matter how well masked or concealed. With a sniff, they can tell whether a new friend at the dog park is male or female. They can even catch the aroma of disease, including cancer, diabetes and, it turns out, epileptic seizures.

Epilepsy is one of the most common neurological diseases in the world. In the United States, it afflicts nearly 4 million people. Worldwide, this number reaches 50 million. Though epileptic seizures seem to come on suddenly, without warning, subtle clues emerge ahead of the attack via changes in scent: The body releases volatile organic compounds, or VOCs—molecules that can travel through the air. Dogs can detect these VOCs about 15 minutes before a seizure begins and alert their companions.

“Some bark, some pace, and some pull on sleeves,” says Gary Arnold, whose sister trains dogs to assist humans with epilepsy and other conditions. Even untrained dogs know that something is about to go awry, which they typically manifest in specific consistent behaviors to attract attention, Arnold says. “It’s sort of individual to each dog and their relationship with their person, but it becomes very clear, once you know what they’re doing.”

Subtle clues emerge ahead of the attack via changes in scent.

These warnings can be critical for people with epilepsy. Seizures come in many varieties, but can render a person totally unable to function in an instant. Symptoms can include involuntary movement of the limbs or the entire body, loss of consciousness, or loss of control of the bowel or bladder. While medications can be effective for 7 out of 10 people, for the rest, driving may become dangerous and, depending on how often the seizures strike, travel of any kind may be a gamble. Some people with epilepsy become hermits, afraid to leave the house, held hostage by their unpredictable bodies.

Unfortunately, there aren’t enough dogs, and particularly enough trained ones, for every person suffering from seizures. Training dogs takes time and is expensive. So a few years ago Arnold envisioned a different solution to the problem—an electronic device that can detect the same scent molecules that dogs do.

After a few years working together with researchers from Florida International University, Arnold zeroed in on a handful of molecules. “There were very unique VOCs being created in the body before, during, and just after a seizure,” he says—and they weren’t present at any other times. He narrowed the selection down to the three “primary VOCs” that are always present regardless of the type of seizures a person is having. With that information, he contacted Sandia National Laboratories, a government research institution that is part of the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration.

Arnold read that Sandia scientists had been working on a handheld device that was able to detect airborne molecules of explosives. “That’s exactly what we needed,” he says. “We just need different targets.” Phillip Miller, a researcher at Sandia, says the laboratory was keen on the idea and began to work with Arnold. An early alert wearable, they realized, would allow people with epilepsy to better prepare—for example, to leave a business meeting and find a private, safe place. Or, if their seizures respond to medications, to take the pills.

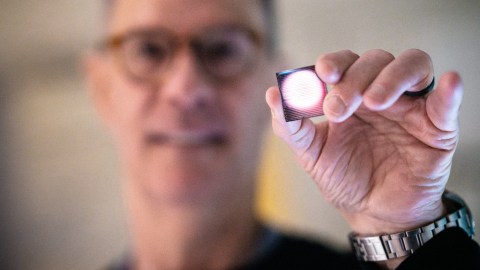

After about two years of work, the collaboration yielded the first-ever prototype of a seizure-predicting device that can sniff out the telltale molecules. Currently, it’s the size of a hardcover novel and can be worn on the body like a backpack. Arnold wants to shrink it down to the size of a large watch. It consists of an absorbent material that soaks up the VOC molecules from the body. These are then passed through a gas chromatograph, which detects the presence of the culprit VOCs.

So far, the device, which will be marketed through Arnold’s company Know Biological, has been tested on about 50 people, and Arnold is gearing up for many more through the end of this year. He hopes it will be on the market by the end of 2024. Whether the size of a small backpack or a wristwatch, it could make millions of people’s lives much more manageable.

This article originally appeared on Nautilus, a science and culture magazine for curious readers. Sign up for the Nautilus newsletter.