6 essential books on existentialist philosophy

- Existentialism deals with the search to find meaning through free will and choice, among other things.

- Philosophers considered are existentialists who hailed mostly from Europe in the 19th and 20th century.

- Many existentialists believe that humans should make their own worth regardless of rules, laws or tradition.

There is a wide variety of ideologies that comprise the existentialist school of thought. Although these views may vary, each is concerned with the individual and their freedom within the world and society. In the realm of philosophy, existentialism is one of those labels that came after the fact in order to describe a diverse set of ideas that share similar ideals.

Many of the ideas in the so-called existentialist strain are difficult for some people to deal with and will put your mind to the test. Some wallow in the pure dread of an uncaring world while others laugh in the face of suspected meaningless. But that’s the fun of it.

So if you make it through all of these books without developing a crippling hollowness inside your soul or blackened void (you decide), then head on over to this diverse metaphysical book list for some lighter reading and develop that philosophical palette even more! Or not, because, well…who cares anyways? But ye I also say! Ascend to greater heights and become greater than yourself and say yes to the day. And as you’ll see, existentialism is quite diverse.

Here are six existentialism books that offer a solid introduction to the philosophy.

1. The Stranger by Albert Camus

The writings of Albert Camus are the premier oeuvre of existentialist literature. The Stranger follows the story of a regular guy, Meursault, who is unintentionally drawn into a murder on an Algerian beach. Translated into English by Matthew Ward, the novel explores what Camus himself referred to as “the nakedness of man faced with the absurd.” Anything by Camus will leave you in awe, but The Stranger really delivers.

The famous opening lines “Mother died today. Or maybe it was yesterday, I don’t know,” set the stage as emotionless and removed Meursault drifts through the absurd situations he’s placed in.

Throughout his books, Camus would eventually develop a philosophy he considered absurdism. “The Absurd” being the conflict between man’s tendency to seek meaning paired with the usual inability to ever find anything purely meaningful in an irrational existence. This is best explained in his essay The Myth of Sisyphus.

Albert Camus believed that the best life lived should embrace this inherent contradiction.

“It was previously a question of finding out whether or not life had to have a meaning to be lived. It now becomes clear on the contrary that it will be lived all the better if it has no meaning.”

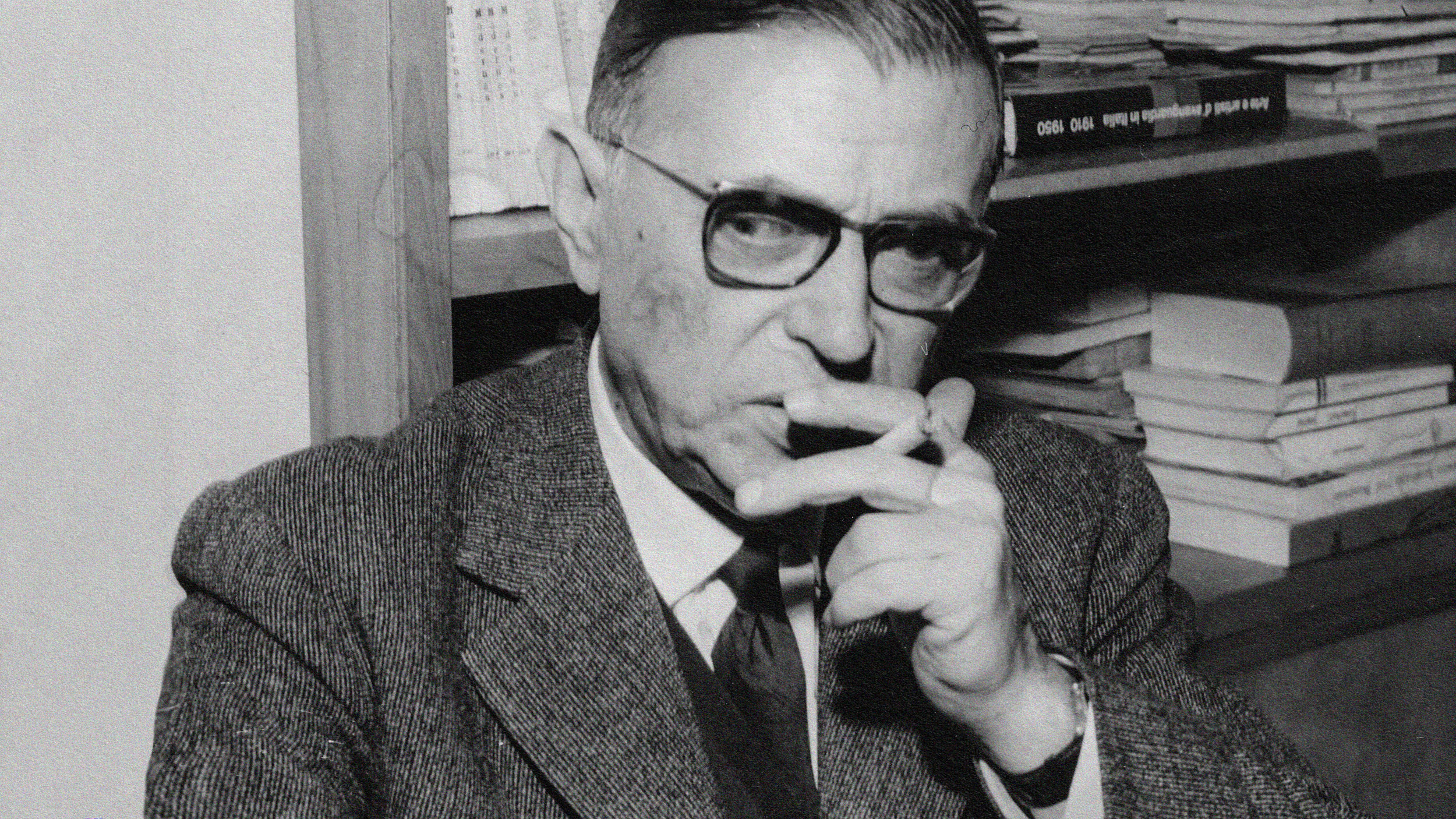

2. Being and Nothingness by Jean-Paul Charles Sartre

Novelist, playwright, and biographer Jean-Paul Sartre is considered by many to be one of the greatest and most profound philosophers of the 20th century. Being and Nothingness is a fundamental text of existentialism. It’s also a hefty read for those not already familiar with a lot of philosophical texts.

Sartre begins his roaring treatise first on the subject of nothingness, which he contrasts to the fact that it is supported by being, although it does not have it. Eventually he establishes two main points which are considered Being-for-itself and Being-for-others.

The most important theme of the book deals with the idea of people fleeing from their own freedom. Sartre’s philosophy and main ideas are formed at the bedrock by his knowledge on a wide range of subjects, including philosophy, biology, physics, among others — at least up to the time he wrote this book in 1943.

For Sartre, humans define their meaning and have absolute control and freedom over all of their choices. He considers the following a basic statement of fact.

“I must be without remorse or regrets as I am without excuse; for from the instant of my upsurge into being, I carry the weight of the world by myself alone without help, engaged in a world for which I bear the whole responsibility without being able, whatever I do, to tear myself away from this responsibility for an instant.”

3. Thus Spoke Zarathustra: A Book for All and None by Frederich Nietzsche

Zarathustra is Friedrich Nietzsche’s absolute masterpiece. An influential philosophical work that would go on to inspire some of the greatest minds of the 20th century and will continue to do so for many years to come. It’s also a tremendous work of literature with its highly stylized poetic language. If you’re looking to dive into Nietzsche, this is a book you might want to put off until you’ve read some of his earlier works. It is in this book that he fully lays out, albeit quite poetically, the crowning ideal of the Übermensch, or “overman” — which he believes will be the grand and ultimate goal for the human race.

Vastly misunderstood throughout the years by despotic regimes and countless other misguided idealogues, one wonders if any of these people actually even read Nietzsche past a quick secondary source blurb or other bastardized and blurry reading. Nietzsche would have had a good laugh at their expense as he’d predicted many of these misrepresentations of himself and his philosophy with the character called Zarathustra’s ape.

Yet falsehoods aside, Nietzsche is a writer who is still a great anomaly even to the greatest adepts of his philosophy and readers. He requires a lot of time and contemplation, whether or not you agree or disagree with his views.

The following quote beautifully captures one of the most noble, supreme and highest ideals ever laid to the page:

“Man is something that shall be overcome. Man is a rope, tied between beast and overman — a rope over an abyss. What is great in man is that he is a bridge and not an end.”

4. The Trial by Franz Kafka

Written sometime in 1914, while Franz Kafka still believed himself to be a failure of a writer – this book would not be published until 1925, a year after Kafka had died. Inspiring the great turn of a phrase — Kafkaesque — The Trial is Kafka at his clearest and most absurd. The book follows a bank officer Josef K., who suddenly gets arrested without reason and without being able to figure out what the charge is. The book begins in a similar fashion to The Metamorphosis, a story in which his character Gregor Samsa is inexplicably turned into a giant bug without explanation.

“Someone must have traduced Joseph K., for without having done anything truly wrong, he was arrested one fine morning.”

The rest of the novel follows suit. It’s a great tale of nonsense bureaucracy, maddening absurdism and just plain existential dread. This is an unfinished novel, but in a way that just adds to the brevity for the many themes of this book.

5. The Last Messiah by Peter Wessel Zapffe

Peter Wessel Zapffe flips the script with The Last Messiah, an essay taken from his book Om det Tragiske, a book written in obscure and idiosyncratic Norwegian that still hasn’t been translated into English. (Author’s aside — someone please do a full English translation.)

This is the text that brings antinatalist thought to the forefront. Zapffe posits that the human condition is a state of eternal despair and it’s all due to humans being over-evolved with a superfluous brain. We are, to Zapfee, a supra-cosmic mistake. Or, as he puts it:

“… a biological paradox, an abomination, an absurdity, an exaggeration of disastrous nature.”

He likens humanity’s intellect to an ancient deer, whose over-evolved antlers proved to be its doom. He states:

“The tragedy of a species becoming unfit for life by over-evolving one ability is not confined to humankind. Thus it is thought, for instance, that certain deer in paleontological times succumbed as they acquired overly-heavy horns. The mutations must be considered blind, they work, are thrown forth, without any contact of interest with their environment. In depressive states, the mind may be seen in the image of such an antler, in all its fantastic splendor pinning its bearer to the ground”

Zapffe considers any wondering from this frightening reality to be part of four defensive strategies in which humans use to cope and shield ourselves from this horrendous tradition. As far as Zapffe was concerned, and pretty much anyone alive today can attest to, we still haven’t figured out any sufficient answer to those deep piercing great questions of existence.

Here are the defense mechanisms:

- Isolation: “By isolation I here mean a fully arbitrary dismissal from consciousness of all disturbing and destructive thought and feeling.”

- Anchoring: “The mechanism of anchoring also serves from early childhood; parents, home, the street become matters of course to the child and give it a sense of assurance.”

- Distraction: “A very popular mode of protection is distraction. One limits attention to the critical bounds by constantly enthralling it with impressions.”

- Sublimation: “The fourth remedy against panic, sublimation, is a matter of transformation rather than repression. Through stylistic or artistic gifts can the very pain of living at times be converted into valuable experiences. Positive impulses engage the evil and put it to their own ends, fastening onto its pictorial, dramatic, heroic, lyric or even comic aspects.”

Zapffe leaves his readers with no transcendental triumph to the future: “Know yourselves — be infertile and let the earth be silent after ye.”

6. Either/Or by Søren Kierkegaard

One of the earliest books for Søren Kierkegaard, it is considered to be a fundamental text for existentialist thought. Kierkegaard wrote many of his works under a pseudonym, and he’d continue to do that throughout most of his career. At around 835 pages for some versions, this is a monstrous treatise, in which Kierkegaard compares two radically different modes of existence: aestheticism and ethics.

In the first part of the book, he follows a young man called “A” who reflects on a great deal of aesthetic topics. If you’ve read Oscar Wilde’s Dorian Gray or that devious little book which Dorian falls prey to, À rebours by Joris-Karl Huysmans, you’ll recognize a lot of similarities in the exploration of sensual dandyism, epicurean pleasure and other assorted delights. Part two departs from this and meditates on the conflict between the ethical and aesthetic, opting for a more moral type of life.

Kierkegaard oscillates between dread and triumph, either / or, this or that, in which he concludes somewhere later on that:

“I see it all perfectly; there are two possible situations — one can either do this or that. My honest opinion and my friendly advice is this: do it or do not do it — you will regret both.”

This article was originally published on Big Think in November 2018. It was updated in April 2022.