Emotional intelligence has limits: Hone your “perceptivity” as well

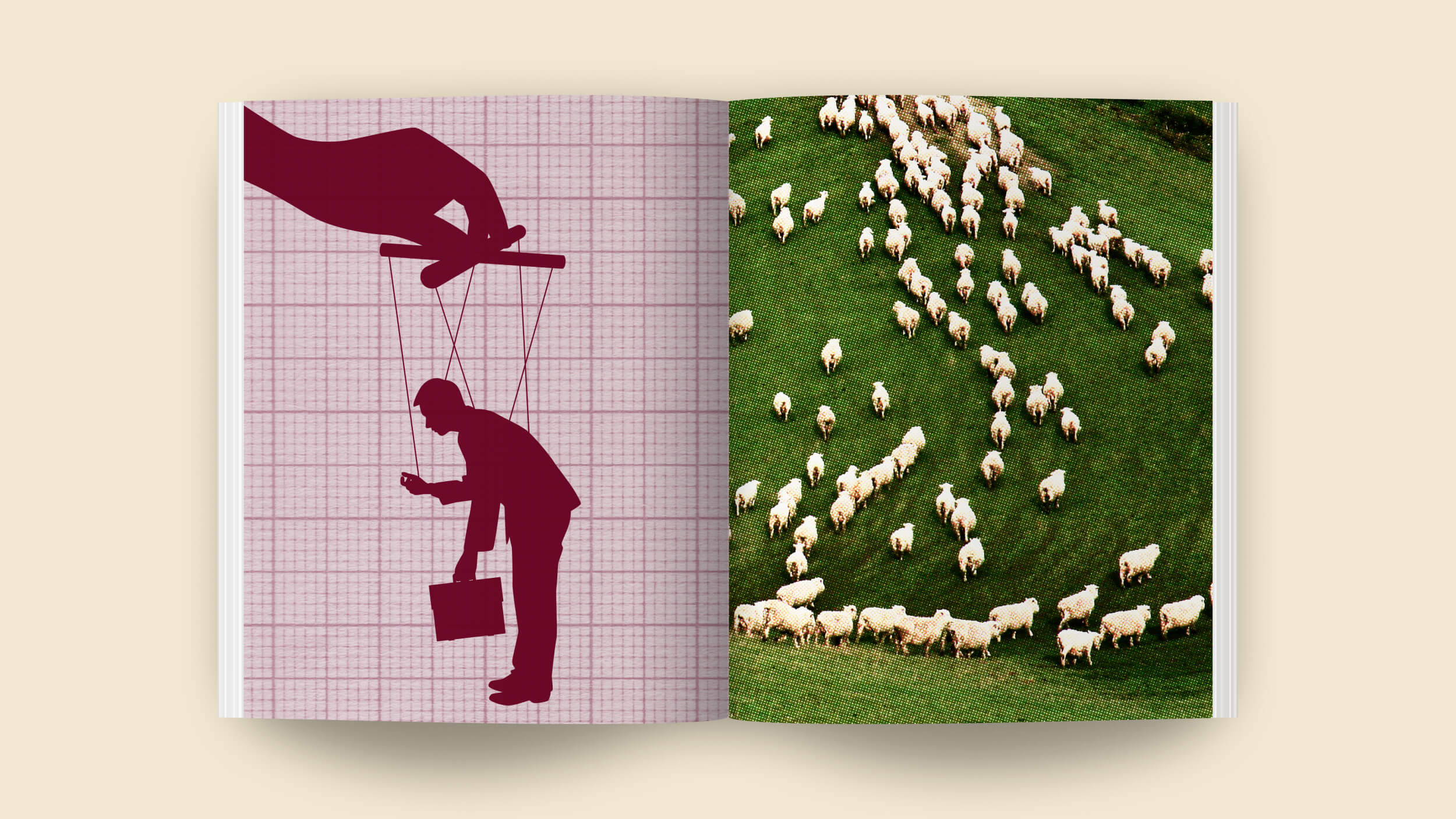

- Emotional intelligence can clue you in to how people are feeling in the moment.

- However, it doesn’t give you insight into the personality traits and deep-rooted issues that help you truly understand someone.

- Perceptivity is linked to better performance and improving it helps you make better people decisions at work.

Most people think they are better judges of character than everyone else. (Of course, that statement is statistically impossible — read it again.) For years scholars cast doubt on this notion, regarding perceptivity as more a learned skill than a natural ability. However, recent research into what is called “the good judge” of character suggests that some people do have an advantage in this area. One 2019 study found “consistent, clear, and strong evidence that the good judge does exist” — in other words, some people are indeed better than others at judging personality.

My own experience bears out this finding. Over my two decades of working with leaders across industries as wide-ranging as private equity, apparel, health care, and agribusiness, I’ve found that some people are extraordinarily adept at judging others, but these individuals are few and far between. The vast majority of professionals think their judgment of others’ personalities is accurate. In truth, they fall prey to a whole range of biases that skew how they size people up and in turn lead to horrible decision-making.

Evidence suggests that how good we are at judging people matters, significantly influencing how we perform. Research psychologists have successfully demonstrated that accurate readings of personality “are important not only for specific professions but also for positions within every organization.” Such readings allow managers inside companies to hire the right people and to provide feedback that will most likely resonate with workers as individuals. They also allow people to make better decisions about whom to trust, whom to interact or collaborate with, and whom to approach with new ideas. Since numerous studies have linked various personality traits with strong job performance, and since those linkages are statistically quite strong, it stands to reason that an ability to spot these personality traits in others affords us a big advantage.

I’ve seen this advantage play out in my own work when it comes to specific decisions that leaders and managers must make. When clients of mine have assessed others poorly or haven’t even bothered to try, they’ve almost always lived to regret it. And when they’ve gleaned others’ personalities well, they’ve made stronger decisions that have paid off handsomely.

Integrating personality insights into decision-making has allowed leaders and companies to achieve great outcomes while working through incredible challenges. At one large law firm we work with, one of the senior partners — I’ll call him David — was abusive, causing grave problems for the organization. On one especially egregious occasion, he spat on a colleague in the lobby of the firm’s office building, in full view of many (if any one of them had recorded it and put it out on YouTube, it would have gone viral overnight).

Others within the firm wanted David fired on the spot. The inconvenient truth was that he was a very effective attorney and a huge breadwinner for the firm. If he left, some of the firm’s highest-profile and most lucrative clients would leave as well, rendering it a shell of its former self.

Human resource managers at the firm brought me in to try to understand what the hell to do with him. More formally, they were asking whether the firm might resolve the problem without having to fire the partner. At first, HR told me it was an issue of emotional intelligence and that this should be the focus of any intervention. I explained that emotions are just part of the story and that to really help I needed to determine which underlying personality factors might be a factor. They agreed and I conducted a psychological assessment of David, which included a deep-dive interview and some formal psychometric tests to gain insight into his personality.

My assessment confirmed that he possessed many traits that allowed him to be successful as an attorney. He was energetic, engaging, persuasive, bold, comfortable with risk — all very helpful for a high-powered lawyer. He also lived by a strong moral code that guided his behavior and caused him to be protective toward those he loved.

It also revealed that he had an anxious, impulsive, and at times combustible personality. If David felt even remotely slighted, he would blow it up in his mind and react explosively. He was ambitious and relentless in his pursuit of success, but in some situations, his passionate nature would manifest as aggression, his anxiety as moodiness, his impulsivity as a failure to consider the consequences of his behavior. He became irritable under pressure, anxious about his performance, and his moral code led to stubborn inflexibility, worsened by a need to always be right. He was a perfectionist, and when things weren’t perfect, he reacted.

Perceptivity affords you a huge advantage over the surface-level shortcuts and stereotypes people typically use when sizing others up.

These aspects of his personality could make it very difficult for David to get along well with colleagues. When triggered, he had a tendency to lash out — just like he did that day in the lobby.

As I told David and his bosses, he couldn’t magically erase these negative aspects of his personality — they were as much a part of who he was as his more adaptive traits. What he could do was become more aware of his behavioral tendencies and take steps to correct or balance them out. In other words, he could do the work to develop a level of personal maturity he didn’t yet have. If he did that, he could develop strategies for moderating his negative tendencies. He wouldn’t be able to eradicate his bad behavior entirely, but he might well be able to reduce the frequency and severity to the point where it was much less disruptive to others.

My message resonated with David. The initial insight he gained into his personality thanks to our testing made a difference; namely, that it helped him to acknowledge behavior patterns he hadn’t fully understood and grasp ways in which his natural tendencies sapped his effectiveness at work. He started to see a therapist and made important progress within a few years. He was able to control his negative impulses while retaining important expressions of his personality that had long contributed to his success. Instead of leaving the firm, he now thrives there, leading to an improvement in the broader work environment.

In David’s situation, it wouldn’t have sufficed to have focused on emotional intelligence. That would have shed light on just a small portion of the problem: emotional regulation. It would never have revealed his deeply rooted issues with authority or his relentless pursuit of perfection and underlying justice mentality.

To understand people, you need to know more than just their state emotions, those fleeting feelings and how they’re expressed. You must understand the building blocks of who they are as people — their personalities. You need to know how they think, how they interact with others, what motivates them, what trait emotions (e.g., a “happy person”) they possess, and how they work.

Like the X-ray machine in a doctor’s office, perceptivity can give you a picture that is sufficiently detailed and accurate to be practically useful in your day-to-day life.

Given the links between perceptivity and performance, you might wonder if you can improve your ability to observe others and grasp who they really are. The good news is, you can. Moreover, improving perceptivity will make you a better judge of character and a better person for it. Studies have found that good judges of personality tend to be more relationship-oriented, agreeable, and positive-minded than others. But even if we don’t happen to naturally possess those traits in abundance, we can still cultivate specific skills, habits, and tendencies that allow us to take the measure of people as individuals.

To be clear, utilizing this tool won’t give you a perfect picture of yourself or anyone else. But like the X-ray machine in a doctor’s office, perceptivity can give you a picture that is sufficiently detailed and accurate to be practically useful in your day-to-day life. Perceptivity affords you a huge advantage over the surface-level shortcuts and stereotypes people typically use when sizing others up. Seeing beyond race, religion, socioeconomic status, political beliefs, and other superficial characteristics, you can understand core character and make better people decisions based on it.