Is Abortion the Most Futile Policy Debate Ever?

Is abortion the most futile policy debate ever?

Sometimes I wish the entire country would enter collective, premature menopause just to end it, already.

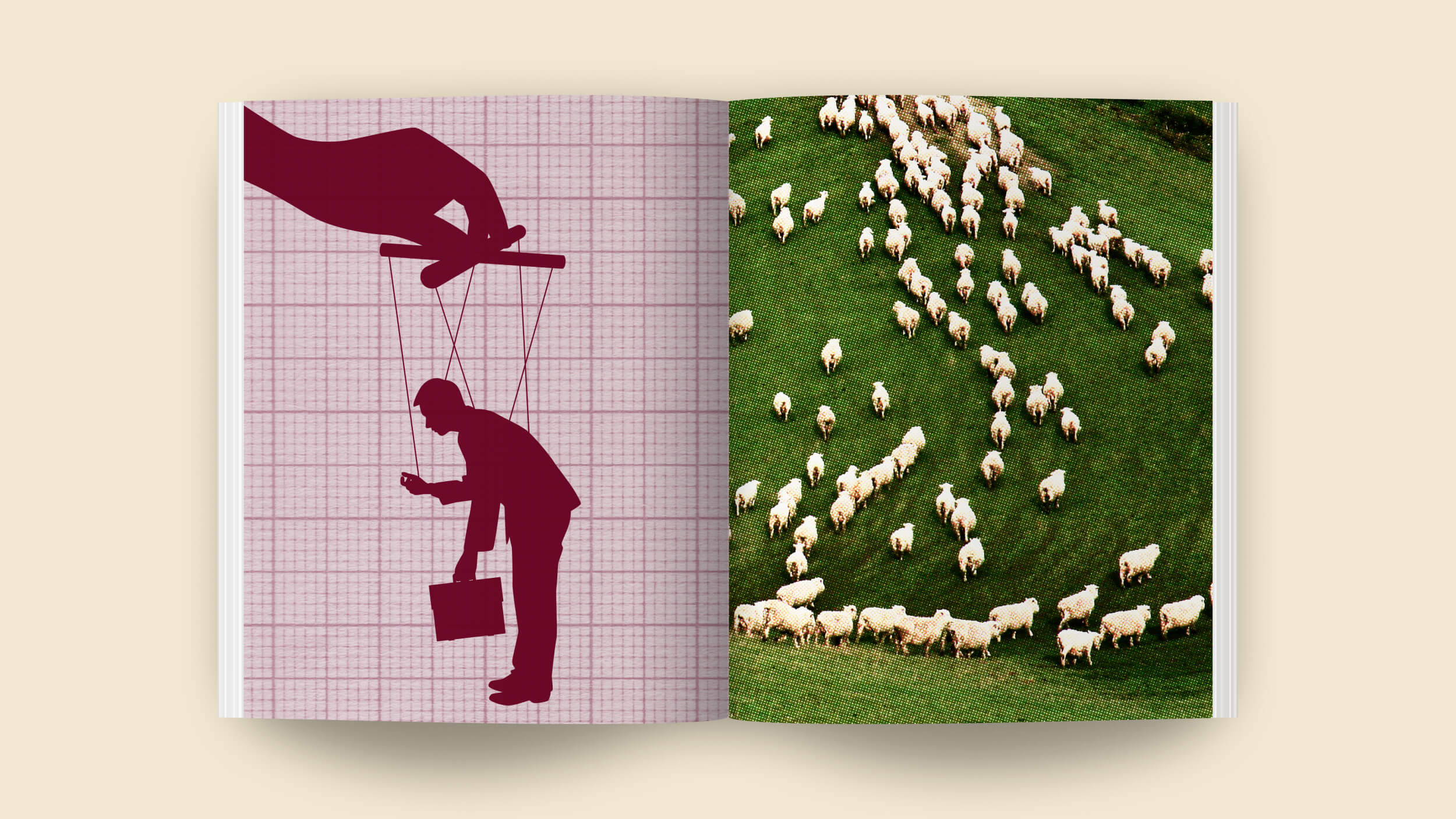

The anti-abortion initiatives and state laws themselves get more extreme— such as the anti-abortion legislation in Texas—but these laws happen not because opinions change tectonically, but when a legislature reaches a tipping point. I don’t think politicians in this matter reflect the general will, which is less extreme.

Opinions in the Gen Pop don’t change all that much. The movement, such as it exists, seems to be that the issue until recently, at least, had diminished in importance for liberals, with conservatives firming up their opposition and endorsing more uncompromising stances, and younger people somewhat but not dramatically less in support of Roe.

But as it is in physics, so it is in abortion politics: An opinion at rest tends to stay at rest.

The intellectual stagnation of abortion politics contrasts with same-sex marriage, where opinions have moved dynamically in the past decade. I’ve written before on the reasons for this.

For one thing, same-sex marriage has a strong foothold in one of the foundational and cherished items on the social conservative agenda: The support of marriage as an institution, and the desire to buttress monogamy. Same-sex marriage converges with this agenda, even as it diverges in other respects.

The political tactics in the same-sex marriage debate have been audacious and uncompromising. Same-sex marriage advocates for the most part have been clear that they want all of their rights—marriage, period—rather than compromises. They haven’t hidden behind euphemisms designed to please the unpleasable.

And that brings me to a problem with abortion politics. It’s a dishonest debate today.

Sometimes an undaunted commentator will try objectively to explain the pro and con sides according to big, abstract, rational principles of American Democracy in Conflict, but they’re missing the entire soul of the debate, which isn’t about intellectual faultlines, or the clash of noble abstractions, but profoundly emotional wellsprings. These emotions may then get transliterated into the dispassion of Big American Principles in Conflict, but that is not what really animates the issue.

The sides often don’t name or state accurately the incandescent things that they feel in their guts. They euphemize instead.

For the pro-choice side, if you listened to mainstream discourse, you’d think that abortion was all about “choice,” whatever that precisely means, or “women’s health,” whatever that precisely means.

The Great Unmentionable pro-choice issue is women’s sexual freedom and agency. It’s about the fact that women of all ages and marital statuses are having sex. They are having sex in a variety of ways, and consensually. They have sex for sex’s sake, and not for the sake of marriage or motherhood. Although they’re imagined as promiscuous, most have sex in relationships. Many enjoy sex. Their male counterparts enjoy this lifestyle, too.

But sexual agency and freedom, expressed as such, aren’t winning ideas these days. This animating passion is almost never elaborated bluntly. You don’t hear, “We believe that women’s sexual agency and freedom is a foundational idea of 21st-century society.”

Instead, pro-choice forces seek shelter behind choice and women’s health, and invoke the most wrenching, non-consensual cases of pregnancy resulting from rape or incest as examples, or emergency medical conditions where abortion is clinically required to save the mother’s life. Those cases are obviously important to include in the political repertoire.

But many more pregnancies terminated in abortion come about through consensual sex. Not citing those examples, and going instead for the non-consensual victims who “through no fault of their own” require abortion signals that we ourselves are mildly ashamed of women’s sex lives, desires, and agency, the forces by which many of us get pregnant in the first place.

For much of the pro-life faction, abortion is about faith, pure and simple. This group of pro-lifers has a faith-derived conviction about what constitutes a life. This position has often been very obvious and prominent in the discourse, from the Christian Coalition onward. It’s notable here not for its obscurity in the debate, but for its intractability. Good luck moving people off of it.

But in the last few years, in state-level campaigns, even this faith position has gotten encoded into fanciful paternalism toward pregnant women: Opposition to abortion is about “loving” women, and women not being exploited by abortion providers, and their health, and their right to know through trans-vaginal sonograms what’s going on in their own bodies. For a comparatively well-articulated example, listen to this Diane Rehm show.

Take these paternalistic, quasi-scientific pretexts at face value if you like, but fierce opposition to abortion has nothing to do with the availability of hospital-grade gurneys in clinics.

Another unspoken but animating force in the pro-life faction, itself a euphemism, is misogyny toward a large group of women. The two—faith and misogyny—aren’t mutually exclusive. You could have both, or one, or neither, of these feelings. I’m not saying that all abortion foes feel this way.

Although the word misogyny might sound accusatory, I don’t actually mean it that way today. I mean it dispassionately as the most elegant, descriptive term available.

It might be a welcome candor, to hear someone say, “I oppose abortion because I really hate these liberated women running around, and I hate their sex lives.” Maybe Erik Erickson might have said that instead of tweeting that liberals should now invest in coat hangers.

There are both men and women in the pro-life movement who have a visceral contempt for modern women, and the world that they blame on the caricatured sexual revolution of the late 1960s. The best evidence for this hypothesis would simply be a review of Comments sections where, under cover of anonymity, and in a literally subtextual space, opponents will express how much they loathe the women they imagine to be irresponsible sluts.

These particular abortion opponents “hate our freedoms,” to recall George W. They hate women’s sex lives outside of marriage, their liberation, and their non-maritally and non-procreatively defined lives. Abortion is a currency by which to express that dismay.

This subset might be willing to let embryos be destroyed in the cause of fertility treatments, at fertility clinics, but not in abortion clinics, when a woman is trying to avoid motherhood rather than achieve it. Or, they might support abortion so long as the pregnancy resulted from non-consensual sex.

I’m glad that they have this compassion, not to expect a victim of incest or rape to carry her abuser’s baby. But their stance also reveals how their feelings are tied to judgments of what women “deserve” to get, contingent on whether or not they wanted to have sex.

The phrase a war on women is groping after “misogyny,” but it’s too muffled by martial-rhetorical mumbo jumbo to do the job.

Maybe it’s time to clear the table of the euphemistic clutter, on both sides. Anything can be gotten over and resolved, even the most extreme feelings and conflicts (and even though we’ve long ago given up on the idea of political efficacy and transformation) but only if they’re confessed.