Doggerland, the Missing Link Between Britain and Europe

Word of the day: epeiric. That term describes shallow, salty seas covering part of a continental shelf. Examples include the Sundance, Zechstein and Turgai Seas – all excellently named, but alas all dried up. Epeiric seas still around today include the Hudson Bay and the Persian Gulf. And the North Sea, of which we shall now speak.

Some 10 millennia ago, during the last Ice Age, so much water was stored in huge polar ice caps that sea levels were 120 m lower than today. The North Sea consequently wasn’t a sea, but a land bridge between Britain and Europe. Geologists call this Doggerland, after the Dogger Bank, the shallowest, largest sand bank in the North Sea today. In all probability, this now sunken land land of once undulating prairie was quite densely inhabited by Stone Age humans. These must have been their hunting grounds, their prey the mammoths whose bones fishermen sometimes still dredge up from the sea floor.

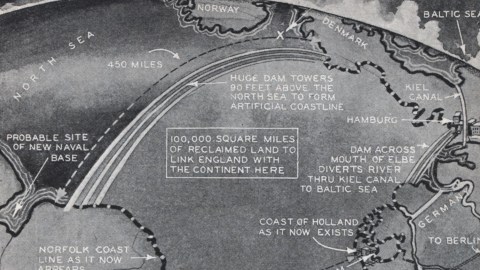

In the 1930s, there existed at least one wild plan to reclaim this particular piece of sunken real estate from the seas, if maybe only in the pages of Modern Mechanix, an American magazine (1928-2001) that ran under a variety of titles (the best-known perhaps being Mechanix Illustrated). This map, dated to September 1930, has a slightly unbelievable air to it, and its inspiration probably isn’t Doggerland, but might well be the better-argumented Atlantropa scheme (discussed in #287 of this blog).

Under the title ‘North Sea Drainage Project to Increase Area of Europe’, a caption reads:

“If the extensive schemes for the drainage of North Sea are carried out according to the plan illustrated above, which was conceived by a group of eminent English scientists, 100,000 square miles will be added to the overcrowded continents of Europe. The reclaimed land will be walled in with enormous dykes, similar to the Netherland dykes, to protect it from the sea, and the various rivers flowing into the North Sea will have their courses diverted to different outlets by means of canals.”

Conspicuously absent are the scientists’ credentials. The logistics of building a 450-mile-long dyke connecting Norfolk (England) to Jutland (Denmark), rising 90 feet above the sea level, seem daunting enough for our own age, let alone for the 1930s. A similar dyke at the North Sea’s south end, barely 150 miles long, would only leave Antwerp and London with direct sea access, depriving the whole of the Netherlands and much of Germany and Denmark of a coastline.

The only element on this map that has become reality, is a fixed link between England and France, although it is a tunnel rather than the bridge imagined on this map. No direct train, then, between London, Berlin, Moscow and the Far East via Harwich (with its abandoned naval base) and passing in between Rotter- and Amsterdam. An inset map at the lower right shows how the map of northwestern Europe might look like, should the North Sea be reclaimed according to this scheme.

Many thanks to Flit for sending me this link to this page at the Modern Mechanix blog. (‘Yesterday’s Tomorrow Today’). And now, just for the fun of it (you never know when it might come in handy), some North Sea trivia:

Strange Maps #296

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].