359 – The Euro Invasion of France (2002)

Gone are the days when crossing a border in Europe almost always meant having to change currencies. Converting guilders into Deutschmark, francs to pesetas, or whatsits into whatnots — all that came to an end on New Year’s Day 2002. The physical introduction of euro coins and banknotes marked the quick phasing-out of a dozen national European currencies (1).

The euro has homogenised a variety of coinage that was as colourful as it was impractical. Euro notes are identical throughout the entire eurozone. The coins still carry a national imprint (2) on one side, though: member states of the European monetary system are allowed to apply national logos and symbols on the coins minted in (or for) their own country; the amounts of these nationally minted coins are obviously weighted: France will produce more French coins than Belgium produces Belgian ones, and Luxembourgish euro coins will be rarer still.

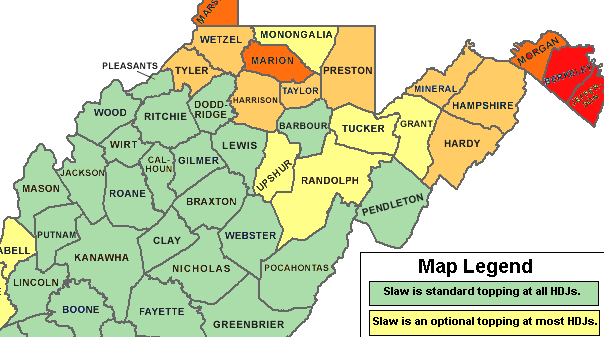

Whichever national imprint these coins may have, they are perfectly valid in any other member state of the eurozone (3). This principle has given rise to a whole new discipline for statisticians to get excited about – euro-coin-analysis, thus observing the flow of money, thereby studying cross-border mobility and ultimately transnational economic ties. An early example of this discipline is this map, drawn up based on data collected in France in the crucial changeover year 2002.

The researchers asked over a million people to show them the change they had on them, counting how many coins were ‘foreign’ and where those came from (in 1992, the average French person carried 14 coins of change, incidentally). This study was published in the November 2002 issue of Population et Sociétés, the monthly newsletter of the INED (Institut national d’etudes demographiques) in Paris. This map charts the infiltration of Belgian, German and Spanish coins. The study itself was more comprehensive. Some results:

Many thanks to Jean-Michel Muyl for alerting me to this map, found here on the aforementioned INED website. Mr Muyl, one of those Frenchmen that doesn’t need prompting from statisticians to cogitate upon the miracle of European monetary integration, says that “still now, it’s an amazement to me to have in my pocket a Dante Alighieri, an Juan Carlos, or an Athena’s owl,” referring to Italian, Spanish and Greek euro-coins.

—

(1) The euro, as an element of the European Union’s goal of an “ever closer union” is a political as well as an economic instrument. It is intended as the single currency of the EU — but three of the 15 EU member states at the time opted out of the system: the UK, Denmark and Sweden. The countries that did introduce the euro on 01-01-2002 were: Austria, Belgium, Germany, Finland, France, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal and Spain. The euro started out as a weighted average of these 12 countries’ currencies. ‘Euroland’ now consists of 16 of the 27 current EU member states, plus three non-EU-states that have adopted the euro with EU permission (Monaco, the Vatican and San Marino) and three more that have done so without permission (Montenegro, Andorra and Kosovo). Eventual introduction of the euro – when the right fiscal, budgetary and economic conditions are met – was a prerequisite for the accession of the newest, eastern EU member states.

(2) the national imprint obviously can only made by countries officially in the eurozone, including the Vatican (the relatively small number of Vatican coins makes these rather sought after collectors’ items) but not Montenegro, Andorra and Kosovo.

(3) Unlike for example Scottish banknotes, which may be refused in the rest of the UK.