Humanity needs an ethical upgrade to keep up with new technologies

- Technological advancements like nuclear weapons, genetic engineering with CRISPR, and artificial intelligence present significant ethical challenges and responsibilities.

- While it’s rational to be concerned about technological threats and dilemmas, many people react by blaming scientists or science itself, failing to recognize the difference between those who control the application of scientific findings.

- Marcelo Gleiser explores this misconception and argues for implementing a biocentric code of ethics that percolates through all sectors of society, from elementary schools to corporate boards.

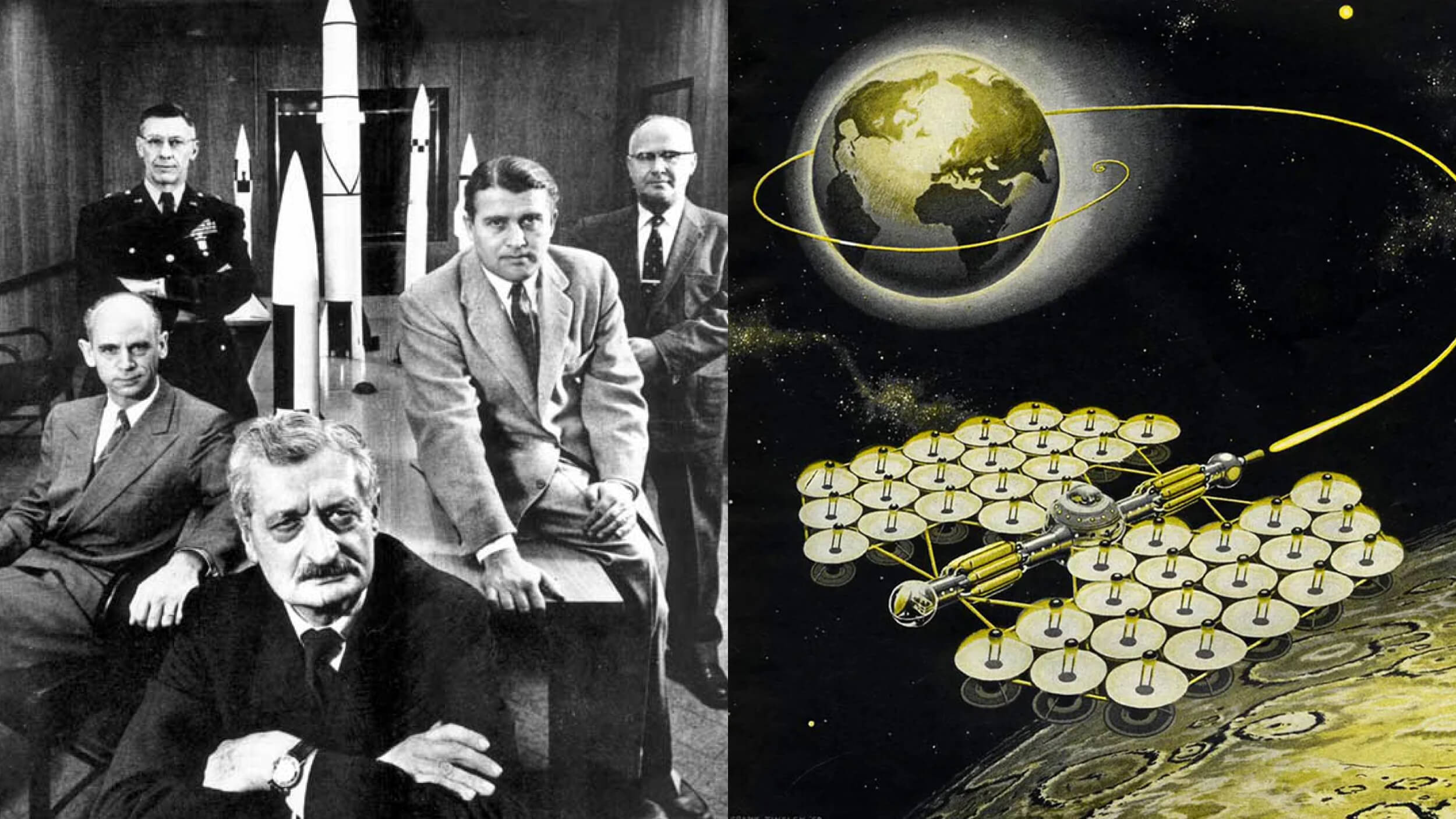

Last week, I discussed the making of the atomic bomb with 65 students taking my class at Dartmouth. The goal was to contrast the scientific challenge of building the bomb during the Manhattan Project with the decision to drop two bombs in Japan. The essential tension is that, even though scientists created the bomb, they had little to no say in how it was (or was not) to be used. If you’ve watched Oppenheimer, this point was made quite clear in the movie.

I complemented the discussion of the atomic bomb with the Big Think video featuring Nobel-Prize winner Jennifer Doudna about the genetic engineering tool called CRISPR, which enables scientists to alter the genetic code directly, as you would — in a somewhat simplified analogy — edit text on a word processor.

As Doudna says in the video, the initial giddiness of inventing a technology capable of healing countless genetic ailments was soon overcome by the terror of how this technology could be used with evil intent. You could imagine a resurgence of eugenics, for example, or the selection of specific physical and intellectual traits that could forever alter the human genetic code. Given the high costs of the procedure, this could create a serious social imbalance and a literal genetic split within our species: the “normal” humans and the “CRISPR-modified” humans.

With CRISPR, we have the potential to reinvent the human species. Add generative AI to the mix, and the conflict between what new digital and genetic technologies could or should do becomes clear.

Navigating modern tech’s moral maze

I asked ChatGPT to define generative AI. A disturbing statement came at the end of the answer:

“One of the key aspects of generative AI is its ability to create novel content that wasn’t explicitly present in the training data, which can lead to surprising and creative outputs. However, ensuring that the generated content is of high quality and doesn’t exhibit undesirable behaviors (such as generating biased or inappropriate content) is an ongoing challenge in the field.”

In other words, the program can create “surprising and creative outputs” with no guarantee of “high quality” or unbiased content. Information with the power to misinform, bias, and polarize would be accessible to users. Today’s AI is an oracle with no solid moral grounding.

Taken together, the nuclear threat (there are still an estimated 12,500 nuclear weapons at the ready in the world, with 9,600 in military service), bioengineering, and current and future AI developments have redefined the playing field between scientific innovation and the ethical use of technology. One essential difference between the nuclear threat and the others is one of scale: Nuclear technology is expensive and needs industrial-scale production. (Of course, you can always consider dirty bombs or small-scale contamination efforts in urban areas as acts of terrorism, but these aren’t the same as all-out nuclear warfare.)

In contrast, bioengineering and AI are more accessible to the public. The documentary series Unnatural Selection illustrates that biohacking, while easy to engage in, poses significant challenges for regulation. Similarly, while AI technologies are complex to develop, they are relatively easy to deploy once created. This accessibility increases the risk of ethical misuse, making regulation difficult to enforce.

Misplaced blame

When faced with such technological threats, the first reaction is to blame the scientists. Very possibly, the anti-science campaign that we see on social media is a response to this collective fear. Why trust scientists if they are blamed for the dangers of what science can do to society? It’s a fair question (after all, one should always be accountable for his actions), but the story is more nuanced.

More often than not, control of scientific research output is beyond the scientists. They may invent or discover, but they don’t usually control the means of production or market distribution of their inventions. The story of the Manhattan Project makes this clear, as do the many environmental abuses by corporate actions, from the fossil fuel industry to industrial-scale agriculture and biopharma. Current examples include irresponsible drilling and fracking, environmental degradation from meat farming, and unethical or irresponsible medical treatments, such as the overprescription of opioids.

To blame science itself for our current existential threats misses the point, displacing the blame from those who control the uses and applications of science. The two are often very different groups. We have reached a technological tipping point whereby the impact of small-scale scientific research can profoundly alter our collective future. If we’re looking for bad guys in cinematic fashion, they usually aren’t the weirdos in white coats working in labs but rather the folks wearing suits and ties (or maybe T-shirts and Birkenstocks these days) — the ones deciding how their companies are going to make the most profit out of their patents.

Sure, some scientists may also be in these meetings. But the point here is that the need for a profound ethical upgrade on how science is used and sold is not up to the scientists alone. As history continues to show, applied science tends to serve the interests of those in power. That’s where decisions come from. To foster such a change, we need to implement a biocentric code of ethics that percolates through all sectors of society, from elementary schools to corporate boards. The preservation and celebration of life, and not greed, should be our primary decision-making value.

It sounds naïve for sure, but the alternative — not doing anything and keeping things as they are — is not only naïve but also self-destructive.