Even if you think of yourself as a human lie detector, there are some untruths that will sneak under the hood. For that, you can thank your brain, and it’s absolute adoration for all things familiar, says Derek Thompson, senior editor at The Atlantic. One of the oldest findings in psychology history is the ‘mere exposure effect’, in which merely being exposed to something makes you biased toward it—parents influence their children by playing certain music around the house that they will love their whole lives, or they instill a political preference in them from an early age. You are drawn to what you know, and that bias really matters when it comes to digital media and the fake news phenomenon. Once something becomes memorable, we tend to conflate familiarity with fact. “This is one of the big reasons why it’s difficult to myth-bust on television or myth-bust in journalism, because sometimes the mere repetition of that myth biases audiences toward thinking that it’s true…” says Thompson. “The mere exposure of news to us biases us toward thinking that that news item is true.” Facebook has an enormous ethical responsibility in this, he says, because it is the world’s largest and most influential news outlet—whether it intended to be or not. Thompson believes there is no algorithmic fix for fake news that spreads via Facebook, only a human one: “The answer to a problem of a lack of human ethics in information markets is the introduction of more humans and more ethics,” he says. Derek Thompson’s latest book is Hit Makers: The Science of Popularity in an Age of Distraction.

Derek Thompson: Two of the favorite terms that I learned in writing this book are fluency and disfluency, and these terms relate to the idea that we have feelings about our thoughts. And that sounds hippie-dippy, but some thoughts feel easy. It feels easy to listen to a song for the 50th time. It feels easy to watch a rerun or easy to read an article that we already agree with. Those are fluent thoughts; those are thoughts that feel good and easy.

But there are also all sorts of experiences, all sorts of types of thinking, that feel difficult and that’s what we call disfluency. So being lost in a foreign country and trying to figure out what all of the signs mean: that is disfluent. Reading an article that is trying to express a position that you consider morally abhorrent: that is disfluent too.

But what’s most fascinating about fluency and disfluency is how they exist together. So imagine that you’re in that foreign country and you’re trying to read all of the signs, and it’s in some Slavic language that you don’t speak and you feel lost and anxious and your brain is hurting with all of these sort of thoughts that are going through it.

And suddenly you turn around and you see an old friend from high school that you immediately recognize and who knows that foreign language. That is an “ah-ha” moment. That is a moment where you transition from disfluent thinking to fluent thinking. And there are all sorts of studies that have said that we love these “ah-ha” moments. We love them in art. We love figuring out art. We love them in storytelling. We love the disfluency of not knowing who the murderer is, and then that moment when—ding!—we got it, we know who the murderer is.

We even love it, I think, in ordinary political opinion writing when someone takes a complex subject and expresses it in such a beautifully clarifying way, it’s like solving a crossword puzzle for politics; we have—click—an “ah-ha” moment.

And I truly think that people are looking for "ah-ha" moments across the cultural landscape. I think that "ah-ha" moments are a large part of what we want from storytelling, what we want from a great education, what we want from a great article or a great book. We are looking for both fluency and disfluency yielding to each other so that we can feel those transition moments that are invigorating and that make us feel like the act of thinking is worth it.

One of the oldest findings in psychology history is called the mere exposure effect. And the mere exposure effect says that the mere exposure of any stimulus to you biases you toward that stimulus. So children who grow up eating more spicy foods tend to like more spicy foods. People who grow up with their parents listening to more jazz end up liking more jazz timbres and more jazz styles.

We have a bias toward familiarity, and I think that this is true both for insignificant tastes—like for food and music—and for profound e.g. political tastes. There’s some evidence that children who grow up in multicultural neighborhoods tend to be much less racist or have much less racial opinions than children who grow up in more monochromatic neighborhoods. Again, this is a bias toward familiarity.

And I think it’s very important to think about familiarity bias as a news consumer, because there’s lots of evidence that shows that the mere repetition, the mere exposure of news to us biases us toward thinking that that news item is true.

This is often how fake news works or how urban legends can start: you hear the piece of gossip once and you dismiss it as mere gossip; you hear it twice, okay maybe now it’s stuck in your head; you hear it from four different people at four different times, suddenly that gossip becomes truth because once it becomes fluent, once it becomes memorable, you tend to conflate fluency or familiarity and veracity or fact.

There was one study that essentially looked at this with scientific facts. They told a bunch of older and younger people that shark cartilage was good for arthritis, and they labeled this fact as false for most of the people that they were showing the fact to. And immediately after the study they asked people: is shark cartilage good for arthritis? And both young and old participants said, “No, we know that it’s not good for arthritis. That fact was listed as false when we saw it in the study.”

But several weeks later they called back the participants and they asked them, old and young, is shark cartilage good for arthritis? The young participants remembered the that the fact was listed as false, but the older participants, who had worse implicit memory, were more likely to say, “Well that sounds familiar, and therefore I think it’s true.”

And so this is one of the big reasons why it’s difficult to myth-bust on television or myth-bust in journalism, because sometimes the mere repetition of that myth biases audiences toward thinking that it’s true, because we have a familiarity bias. We cannot help ourselves from conflating that which is familiar from that which we think is more likely to be true.

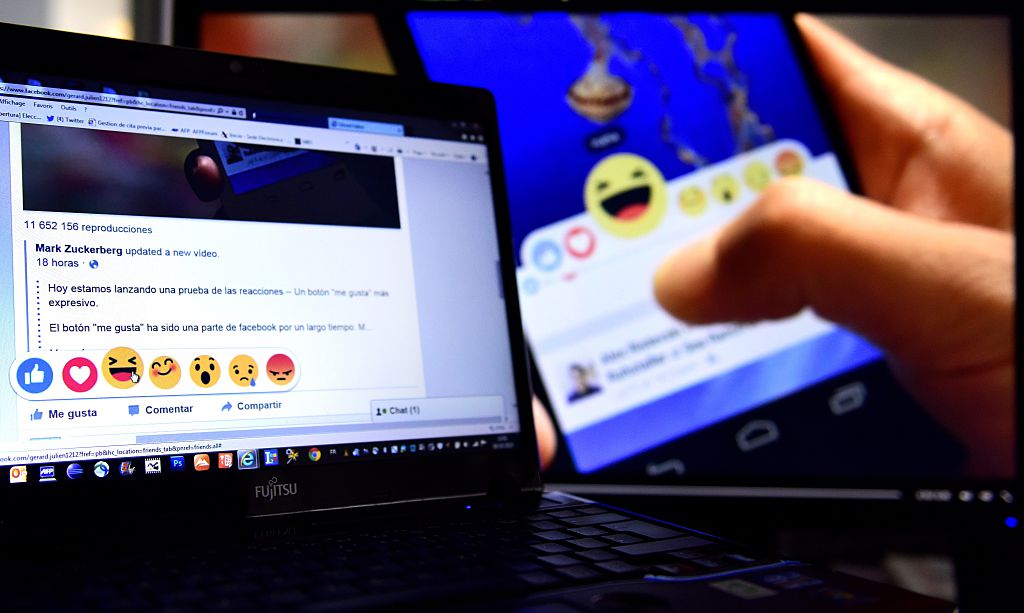

Facebook and Google absolutely have a responsibility to combat this bias, but I don’t know what they can do right now on the technology side. I think that they can hire people. They can hire human beings to go through the news and figure out what is clearly a hoax, what is clearly propaganda, what is clearly meant merely to inflame and not to deliver truth, and they can ban those accounts and ban the people who are responsible for them—even though in many ways that is sort of anathema to Facebook’s fundamental message, which is that 'we are here to unite the world and create a global newspaper for all sorts of opinions and all sorts of content.'

I think that Facebook has accidentally become a media company. They did not, I think, set out to become a media company, but right now for many people they are clearly the global newspaper and the largest distributor of information and content in the history of the world. That is a technology that we’ve never seen before, and so it introduces problems that we’re not familiar with and we’re still grappling with exactly how to answer them.

But I do think that fundamentally the solutions to the problem of fake news on Facebook and other social media sites comes down to human ethics, it comes down to humans—only humans can fix this problem; we don’t have algorithms that can go through and separate fact from fiction. And it comes down to ethics.

The reason that there is fake news out of there is because there are unethical people who are essentially attention merchants. They are not journalists; they don’t want to demonstrate the truth, they don’t want to distribute the truth; they want to make money or they want to inflame people’s emotions.

And it’s difficult to deal with the problem of lack of ethics with anything other than a system of ethics, which right now I don’t think Facebook has fully written into its algorithm.

But one thing that I think about in thinking about Facebook’s news problem right now is back to the invention of the penny press in the early 19th century.

For a long time newspapers were expensive, at six pennies a piece, and then Benjamin Day comes around and he introduces the idea of a penny press. He cuts the price of the newspaper from six pennies to one, he amasses this huge readership and then he sells that readership to advertisers. He invents the dual-revenue business model of news that we still have today, that The Atlantic has, The New York Times has.

But within a few months of starting this newspaper he realized what every other industry in entertainment has also realized, which is that fiction typically outsells nonfiction. Fiction does better in the movie theaters, fiction does better for books, and fiction did better for Benjamin Day when in the 1830s he introduced a huge moon hoax to the American audience, where he told them that there were bat-men living on the moon copulating with each other, in a 17,000 word feature that got enormous readership for his penny press newspaper.

The solution to that problem, the solution to the problem of unethical penny press newspapers, did not come from Benjamin Day; it came from The New York Times. It came from an ethical organization saying: we want journalists from top to bottom who are going to use this dual-revenue business model in order to sell not hoaxes, but news.

And so today, just as 150 years ago, I think that the answer to a problem of a lack of human ethics in information markets is the introduction of more humans and more ethics into information markets.