Radical Theory Overturns Old Model of How Emotions are Made

The classic model of emotion goes something like: You’re born with an innate suite of emotions – happiness, sadness, anger, fear. You feel these emotions by perceiving a stimulus. That triggers a circuit in your brain. That then causes a bodily response, which causes you to behave a certain way.

Emotions happen to you, essentially.

That’s all wrong, says Lisa Feldman Barrett, an author and psychology professor at Northeastern University. In her latest book, “How Emotions Are Made,” Barrett synthesizes research from neuroscience, biology and anthropology to construct a radical new theory of emotion.

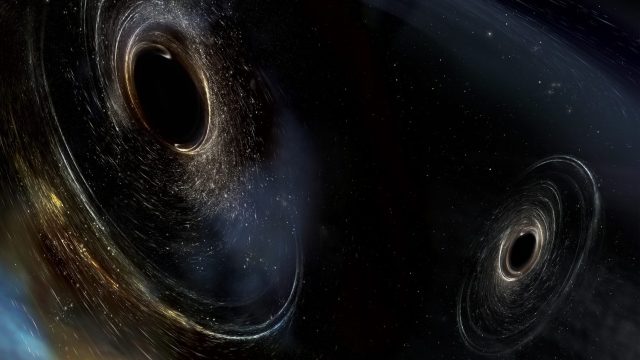

According to Barrett, emotions aren’t reactions to the world. Rather, emotions actually construct our world. And it happens because of interoception.

Interoception is our sense of the physiological condition of our bodies. This sense monitors our internal processes and sends status updates to the brain. Those updates come in four rudimentary signals: pleasantness, unpleasantness, arousal and calmness. Emotions, Barrett claims, are formed from the brain’s attempt to make sense out of this raw data. The brain does this by taking the raw data and filtering it through our past experiences – through our learned concepts.

(From a study that asked participants to interpret emotions by viewing facial expressions.)

This means emotions aren’t objective reflections about events in the world. Barrett elaborated in a recent episode of NPR’s Invisibilia podcast:

“For every emotion category that we have in the U.S. that we think is biologically basic and universal, there’s at least one culture in the world that doesn’t really possess a concept for that emotion and where people don’t really feel that emotion.”

The same concept applies to vision, Barrett suggests, noting cases in which blind people who’ve had corneal damage since birth remained blind for some time after receiving transplants.

“They don’t see for days and sometimes weeks. And sometimes years there are things they can’t see because they don’t have concepts. Their brain has no past visual experience to make meaning of the visual sensations that they receive.

…We would imagine from the classical view that they would just be able to see everything, but they don’t.”

The key implication of Barrett’s theory is both striking and somewhat liberating: We have a lot more control and responsibility over our emotions than previously thought. The concepts we’ve accrued, whether consciously or not, can be learned and unlearned. According to the theory, you have the power to fundamentally change your experience of emotion.

Barrett’s theory has a catch, though. If Barrett is correct, then what should society tell those suffering from, say, PTSD? To sit down and learn some new concepts? Barrett said:

“I see the risk in what I’m saying – right? – but science is science. And we have to – I feel like it’s necessary to draw people’s attention to what the science has to say. And in the proper context in society, in culture, people can debate the consequences. But I think, you know, I do think that it’s very dangerous to treat things as objective when they’re not.”

You can hear Barrett discuss her theory on NPR’s Invisibilia podcast below: