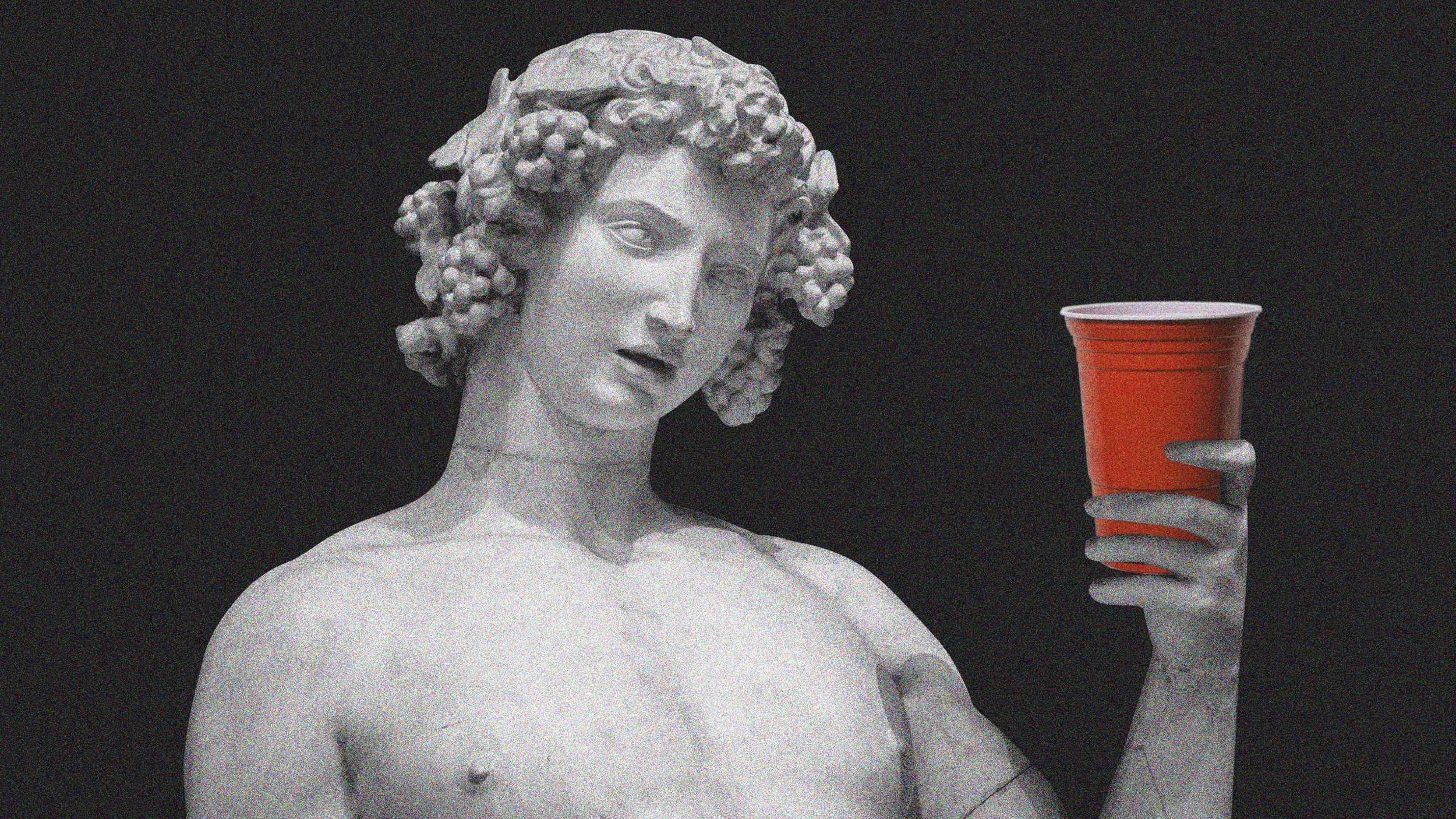

Devil’s Advocates May Be Annoying, but We Need Them More than Ever

Devil’s advocates, it seems, have developed a rather wicked reputation in some circles. In a post at Feministing, Juliana Britto Schwartz unleashed a little hell-fire on people who play devil’s advocate in discussions of political issues:

“You know who you are. You are that white guy in an Ethnic Studies class who’s exploring the idea that poor people might have babies to stay on welfare. Or some person arguing over drinks that maybe a lot of women do fake rape for attention…Most of the time, it’s clear that you actually believe the arguments you claim to have just for the heck of it. However, you know that these beliefs are unpopular, largely because they make you sound selfish and privileged, so you blame them on the ‘devil.’ Here’s the thing: the devil doesn’t need any more advocates. He’s got plenty of power without you helping him.”

Earlier in 2014, Joe Berkowitz offered a typology of contrarians and identified the late Christopher Hitchens as a devil’s advocate who tended to go overboard. “Sometimes,” Berkowitz wrote—when it comes to Mother Teresa’s saintliness, say—“the pot does not require stirring.”

That may be. But as imperious, as annoying and as offensive as contrarians can be, they play an essential role in rooting out prejudice and poor thinking—more essential than even devil’s advocates themselves may recognize. Without people stirring the pot intelligently and relentlessly, groups are doomed to make poorly informed and sometimes dangerously bad decisions. The research in a new book by Reid Hastie, a professor at the University of Chicago, andHarvard law professor Cass Sunstein, Wiser: Getting Beyond Groupthink to Make Groups Smarter, lays out why.

Of the myriad pitfalls imperiling group decision-making that Sunstein and Hastie detail in their book, perhaps the most interesting is polarization. Put simply, whichever perspective a group begins with tends to harden when its members start deliberating. If the consensus view leans toward one point of view, in other words, a group will reliably finish a meeting having moved a few more steps toward that perspective.

“As the psychologists Serge Moscovici and Marisa Zavalloni discovered decades ago, members of a deliberating group will move toward more-extreme points on the scale (measured by reference to the initial median point). When members are initially disposed toward risk taking, a risky shift is likely. When they are initially disposed toward caution, a cautious shift is likely. A finding of special importance for business is that group polarization occurs for matters of fact as well as issues of value. Suppose people are asked how likely it is, on a scale of zero to eight, that a product will sell a certain number of units in Europe in the next year. If the pre-deliberation median is five, the group judgment will tend to go up; if it’s three, the group judgment will tend to go down.”

The phenomenon seems to hold for many types of groups and for a diverse range of issues. In an experiment conducted in two Colorado towns, Sunstein and two colleagues assembled small groups of people who had been pre-screened as left-of-center (in Boulder) and right-of-center (in Colorado Springs). Each group was then tasked with deliberating on three hot-button political questions: climate change, affirmative action and civil unions for same-sex couples. Comparing the individuals’ political views before and after the conversations yielded three remarkable results:

“1. People from Boulder became a lot more liberal, and people from Colorado Springs became a lot more conservative.

2. Deliberation decreased the diversity of opinion among group members….After a brief period of discussion, group members showed a lot less variation in the anonymous expression of their private views.

3. Deliberation sharply increased the disparities between the views of Boulder citizens and Colorado Springs citizens.”

Finding that your initial view is reinforced by people around you inclines you to favor it more strongly, Sunstein says. And a concern for reputation plays a role: people “will adjust their positions at least slightly in the direction of the dominant position in order to preserve their self-presentation” and to be “perceived favorably” by the group. It is a version of the bandwagon effect: once everyone realizes they are inclined in the same direction, they will all move more willingly to the fringes of that position. Differences of opinion get smoothed out; homogeneity increases; diversity of opinion contracts.

This is where contrarians come in. Sunstein suggests that asking “some group members to act as devil’s advocates”—people who urge “a position that is contrary to the group’s inclination”—may help prevent polarization and avert the loss of nuance that comes in its wake. By introducing opposing considerations to a discussion, Sunstein explains, devil’s advocates bring up new ideas that challenge the group’s intuitive positions and force individuals to reconsider their reflexive beliefs.

The plan works best when the contrarian isn’t just playing the part but actually believes, or appears to believe, in what he’s arguing. Otherwise, as Sunstein writes, individuals may be “aware that it’s artificial” and effectively shut their ears to what the devil’s advocate has to say.

John Stuart Mill proposed a similar idea in his 1869 book On Liberty. It is a grave mistake to silence people who hold unpopular views, he wrote. Received wisdom is almost never 100 percent wise. Sometimes it’s flat wrong, and very often its seed of truth is encased in a hull of myth. Eliminating dissenters from the conversation closes off an essential epistemic source. With devil’s advocates attempting to poke holes in the majority’s easy conclusions, it’s a lot less likely that groups will gravitate toward extreme positions that may be inadvisable, socially divisive or even—in insular, radicalized religious movements, as we’ve seen in France— murderous.

—

Image credit: Shutterstock.com