Jonah Lehrer’s Downfall and the Hazards of Genius

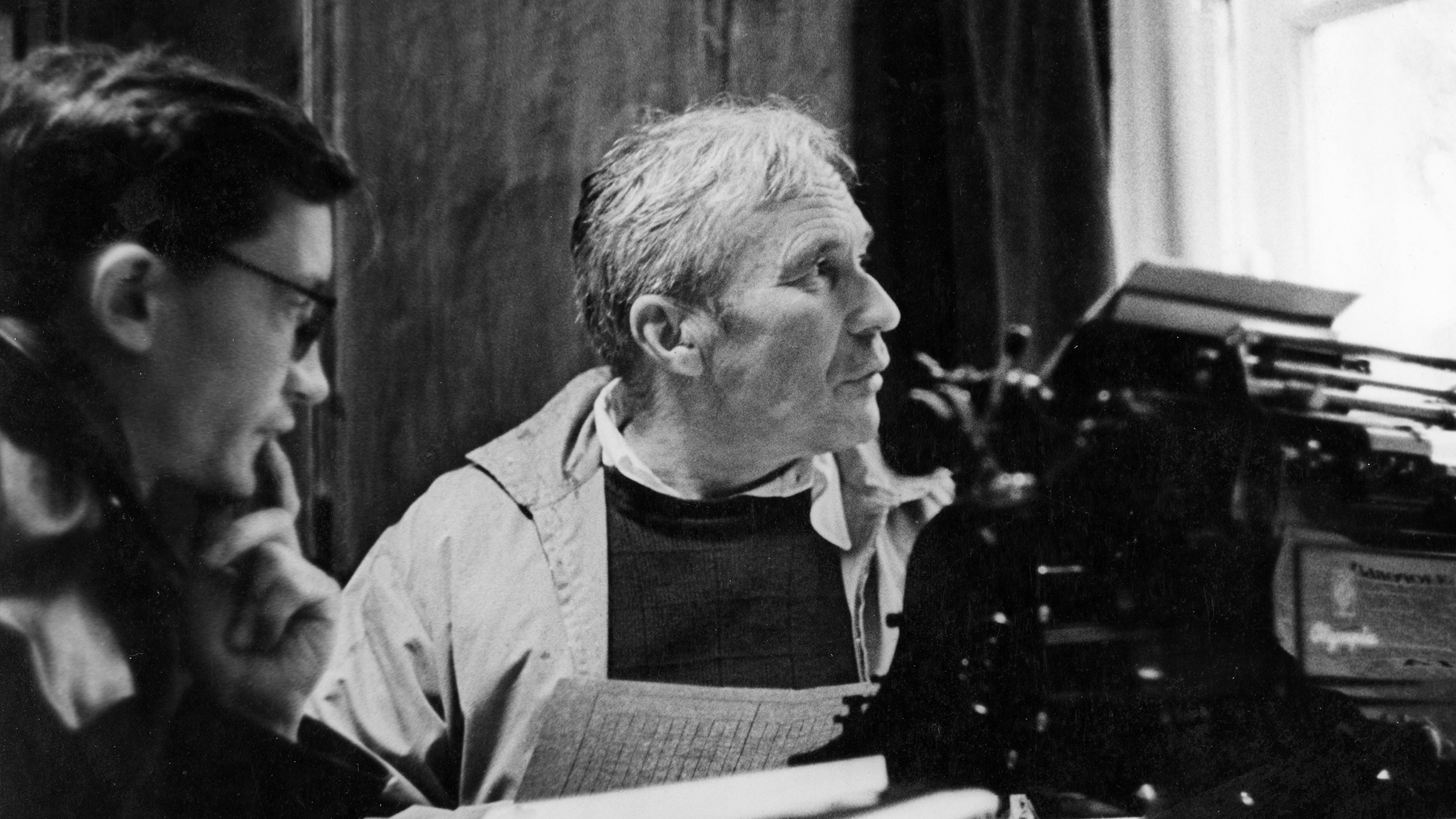

When I heard the news of Jonah Lehrer’s fabrications on Monday — indiscretions that led to an apology and his resignation from the New Yorker on Tuesday — my jaw fell. Like Michael C. Moynihan, who exposed Lehrer in an article in Tablet, I was “completely fucking mystified” why the Rhodes scholar and best-selling science writer would decide to risk his career by putting made-up words into the mouth of Bob Dylan.

After looking up and re-reading some of Lehrer’s writings, I am a little less mystified. Lehrer’s books on neuroscience and human psychology dwell on the foibles of human decision making and the backseat role that reason plays in our choices. Reading Lehrer in the wake of the Lehrer scandal sheds light on what may have happened here. One of his most recent blog posts reads today as a self-diagnosis, or even an admission of guilt.

Let’s start with Lehrer’s second book, How We Decide (2009). In chapter 6, Lehrer develops an argument about rationality, morality and the temptation to cheat that might explain something of what was going on in his head when he imagined a new Dylan line. First consider this passage where Lehrer explains the interplay of reason and emotion when an individual makes a moral decision (emphasis below and in subsequent passages is mine):

It’s only at this point — after the emotions have already made the moral decision — that those rational circuits in the prefrontal cortex are activated. People come up with persuasive reasons to justify their moral intuition. When it comes to making ethical decisions, human rationality isn’t a scientist, it’s a lawyer. This inner attorney gathers bits of evidence, post hoc justifications, and pithy rhetoric in order to make the automatic reaction seem reasonable. But this reasonableness is just a façade, an elaborate self-delusion. Benjamin Franklin said it best in his autobiography: “So convenient a thing it is to be a reasonable creature, since it enables one to find or make a reason for everything one has a mind to do.”

Imagine Lehrer sitting in front of his laptop when he wrote the lines Dylan never said. Lehrer’s creativity and his gift for crafting the perfect sentence led him to a fabrication. And once the lie was there, facing him on the screen, Lehrer’s inner attorney jumped to defend his client: This sentence is good! It is Dylan, even if Dylan didn’t technically say it. Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, listen to this and tell me how pithily it captures the casual genius of Dylan’s music: “It’s a hard thing to describe. It’s just this sense that you got something to say.” Lehrer’s creative process merged with that of his subject. Lehrer became Dylan. And Lehrer’s abstract reasoning process, what Daniel Kahneman calls System 2, failed to boot up. Lehrer just moved on to the next paragraph, happy with what he had created, deluding himself that fabricating the perfect quote and attributing it to a cultural icon is anything but a terrible idea.

Later in chapter 6 of How We Decide, Lehrer tells the story of a professional card counter. The parallels between the shark and Lehrer are almost spooky. And it is obvious that Lehrer is in love with his subject:

“The first thing I learned counting cards,” Binger says, “is that you can use your smarts to win. Sure, there’s always luck, but over the long run you’ll come out ahead if you’re thinking right. The second thing I learned is that you can be too smart. The casinos have algorithms that automatically monitor your betting, and if they detect that your bets are too accurate, they’ll ask you to leave.” This meant that Binger needed to occasionally make bad bets on purpose. He would intentionally lose money so that he could keep on making money.

But even with this precaution, Binger started to put numerous casinos on alert. In blackjack, it’s supposed to be impossible to consistently beat the house, and yet that’s exactly what Binger kept doing. Before long, he was blacklisted; casino after casino told him that he couldn’t play blackjack at their tables.

Lehrer follows Binger’s story as the card counter atones for his sins, enters a Ph.D. program in theoretical physics at Stanford and promptly begins “to miss his beloved card games. The relapse was gradual…” Lehrer presents Binger as a gifted physicist whose brilliance and love of winning led him to moral misdeeds. His extraordinary mind bred vice, and it only dialed back the cheating slightly when too much success would have exposed him too obviously as a fraud. But this defense was as weak as Lehrer’s initial denial of the fabrictions was desperate. Both were bound to failure. We can only hope that Lehrer’s rehabilitation from his blacklisting in the world of journalism has a happier ending.

Even more ominous passages are found in Lehrer’s June blog post discussing new research on bias. After explaining a study’s finding that “intelligence seems to make things worse” when trying to root out the assumption that “everyone else is more susceptible to thinking errors” than we are, he reveals almost too much:

[W]hen assessing our own bad choices, we tend to engage in elaborate introspection. We scrutinize our motivations and search for relevant reasons; we lament our mistakes to therapists and ruminate on the beliefs that led us astray.

The problem with this introspective approach is that the driving forces behind biases — the root causes of our irrationality — are largely unconscious, which means they remain invisible to self-analysis and impermeable to intelligence. In fact, introspection can actually compound the error, blinding us to those primal processes responsible for many of our everyday failings. We spin eloquent stories, but these stories miss the point. The more we attempt to know ourselves, the less we actually understand.

Contrast this deflationary assessment of the prospects for self-knowledge with Lehrer’s stirring, self-helpy final lines of How We Decide:

The first step to making better decisions is to see ourselves as we really are, to look inside the black box of the human brain…We need to honestly assess our flaws and talents, our strengths and shortcomings…We can finally pierce the mystery of the mind, revealing the intricate machinery that shapes our behavior.

Even if he doesn’t fully pierce the mystery of his own mind, here’s wishing Lehrer the time to reflect on his mistakes and the will to pave a path to a less hazardous form of brilliance.

To follow Steven Mazie on Twitter click here: @stevenmazie