The Marathon is Not a Blood Sport

What motivated the perpetrators of the carnage at the Boston Marathon on Monday? Authorities area step closerto identifying those responsible, and we may eventually learn why they decided to detonate bombs at the finish line of America’s premier road race. But the meaning of the attack goes well beyond its propagators’ intentions. This was an act of violence targeting runners and spectators at the most democratic of sporting events, a race that embodies the history and aspirations of democracy like none other.

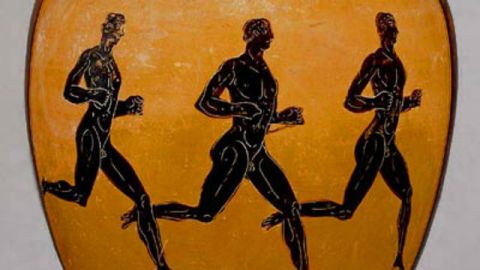

The associations between marathons and democracy stretch back to the first marathon ever run. There was but a single participant, an Athenian citizen named Pheidippides, who expired after completing his famous (ifhistorically contentious) 25-mile dash home to proclaim that the Athenians had defeated the Persian invaders in the Battle of Marathon. Following this victory in 490 BCE, Athensbegan its riseas the world’s first democracy.

In modern times, the marathon (bumped up to 26.2 miles) is the only sporting event I can think of where elites and amateurs alike compete on the same course on the same day. Ever hear of a recreational cyclist joining the riders on the Tour de France? Do weekend warriors run alongside Usain Bolt in the 100 meter sprint? Is there an annual basketball game open to Lebron James, Kobe Bryant and your scrappy 5’8” uncle with the devastating bank shot? No. Though elite runners don’t actually knock elbows with the masses—they typically begin from separate starting corrals and leave the plebeians in the dust—there is something remarkable about such an equal opportunity race. It is a thrill to run a race behind the likes ofMeb Keflezighi,Paula RadcliffeorPaul Tergatand come in faster than you expected (my personal best was3:06on a day I had hoped to run 3:30). As a spectator it is a testament to the variety and tenacity of the human race to see lead runners maintaining a sub-5 minute pace for 26 miles, back-of-the-packers ambling along at 12 minutes per mile, and everybody in between.

Marathons haven’t always been paragons of inclusion, but they have been the locus of battles for equal opportunity. Roberta Gibbemerged from the bushesto run the Boston Marathon in 1966, and a year later Kathrine Switzer became the first woman to officially enter the Boston Marathon (passing under the radar by registering as “K.V.” rather than Kathrine). Switzer was almost pushed off the course by a race official yelling “get the hell out of my race,” but as this image shows, Switzer’s beefy boyfriendintercepted the official (clad in black) and shoved him out of the way so that Switzer could proceed.

It took five more years before Boston would permit women to enter the race. Since then, marathons have been slowly opened up to all comers. The New York City marathon, the world’s largest, added an official wheelchair division in 2000, and visually impaired runners have been welcome at major marathons for some time. Fortyblind or otherwise visually impaired entrantscompeted in the Boston Marathon on Monday.

The 1968 Boston winner, Amby Burfoot, was less than a mile from the finish on Monday for the 45th anniversary of his first-place showing when the bombs exploded. Here ishis reflectionon the tragedy:

It was an attack against the American public and our democratic use of the streets. We have used our public roadways for annual parades, protest marches, presidential inaugurations, marathons, and all manner of other events. The roads belong to us, and their use represents an important part of our free and democratic tradition.

The Boston race adds another dimension to the democratic ethos of the marathon: it is the only large long-distance running competition in the United States most runners must qualify for. This may sound elitist, but the egalitarian foundation of democracy allows for differentiation: individuals with special skills and the drive to apply them can legitimately expect rewards for their efforts. The qualifying times are fast but hardly world-class. They represent lofty but not unrealistic goals for many serious runners who dedicate a few months to rigorous preparation. And they are gender- and age-graded: a 41-year-old male needs to run a 3:15 marathon to qualify while a 60-year-old woman can get in with a 4:25. If you want to run but cannot reach these times, limited entries are available for charities, city officials and local running clubs. Many of these non-qualifying entrants were making their way to the finish line when the blasts broke the peace on Monday.

Any attack of this type is unsettling: we recoil when we see the grisly images of the wounded and weep when we see the faces of innocent victims like 8-year-oldMartin Richardsmiling in happier times. But this week’s marathon bombing is unlike the World Trade Center attacks of 1993 and 2001 and the Oklahoma City bombing of 1995 in this important respect: it happened outdoors, not inside a building. This week we saw the externalization of the terror threat to Americans: you can be a target in the bright sunlight on Patriot’s Day just as easily as you can be killed by a bomb that destroys the building where you live or work.

In Boston this week, people have supported, cheered, protected, rescued, treated, mourned and comforted one another. They have opened their homes to each other and embraced, fed and clothed strangers. While democracy seems to be nothing but a sham these days in Washington, D.C.—yesterday the Senate could not even pass a bipartisan compromise on background checks for gun sales thatnearly 90 percent of the public favors—the democratic ethos of civil society thrives on the streets of cities and towns across the country. The marathon is the epitome of that spirit.

Thanks to Daniel Honan for inspiring this post.

Image credit:Marcio Jose Bastos Silva / Shutterstock.com

Read on: