The Soul in the City – Orhan Pamuk’s ‘A Strangeness in My Mind’

“Boooooozaaaaaaaaa!” “Booooooooooozaaaaaaaa!!”

This cry rings out through the backstreets of Istanbul, from 1969 to 2012 in Orhan Pamuk’s grand, sprawling new novel A Strangeness In My Mind. Words like “comforting” and “reassuring” don’t seem sufficiently “sexy” praise for a literary work on this scale, but these are the only words to describe its effect (on this reader, at least). For all of its 624 pages, I felt enveloped in a sense of deep calm, anchored by Mevlut, a street vendor and the main character, who for four decades, through political convulsions, economic upheavals, and family dramas finds his sense of belonging in wandering the city streets at night selling boza, a thick, spiced, wheat-based, semi-alcoholic winter drink from Ottoman times, and a symbol of all that is sad and beautiful about civilization.

Mevlut is not exactly what you’d call a “go-getter.” Born in a small Turkish village, he follows his father to Istanbul as a teenager to sell yogurt in the streets (a profession soon to be doomed by refrigeration and mass production). Like tens of thousands of other poor workers, they colonize a square of land in one of Istanbul’s growing shantytowns and build a “gecekondu” (“night condo” — so called because they’re built literally overnight) with a dirt floor. For a while Mevlut goes to school, but growing political tensions in the city between nationalists and Kurds soon tear his high school apart, and Mevlut’s too exhausted from nocturnal work anyway to be much of a student. Ultimately, inevitably, he drops out and becomes a full-time street vendor.

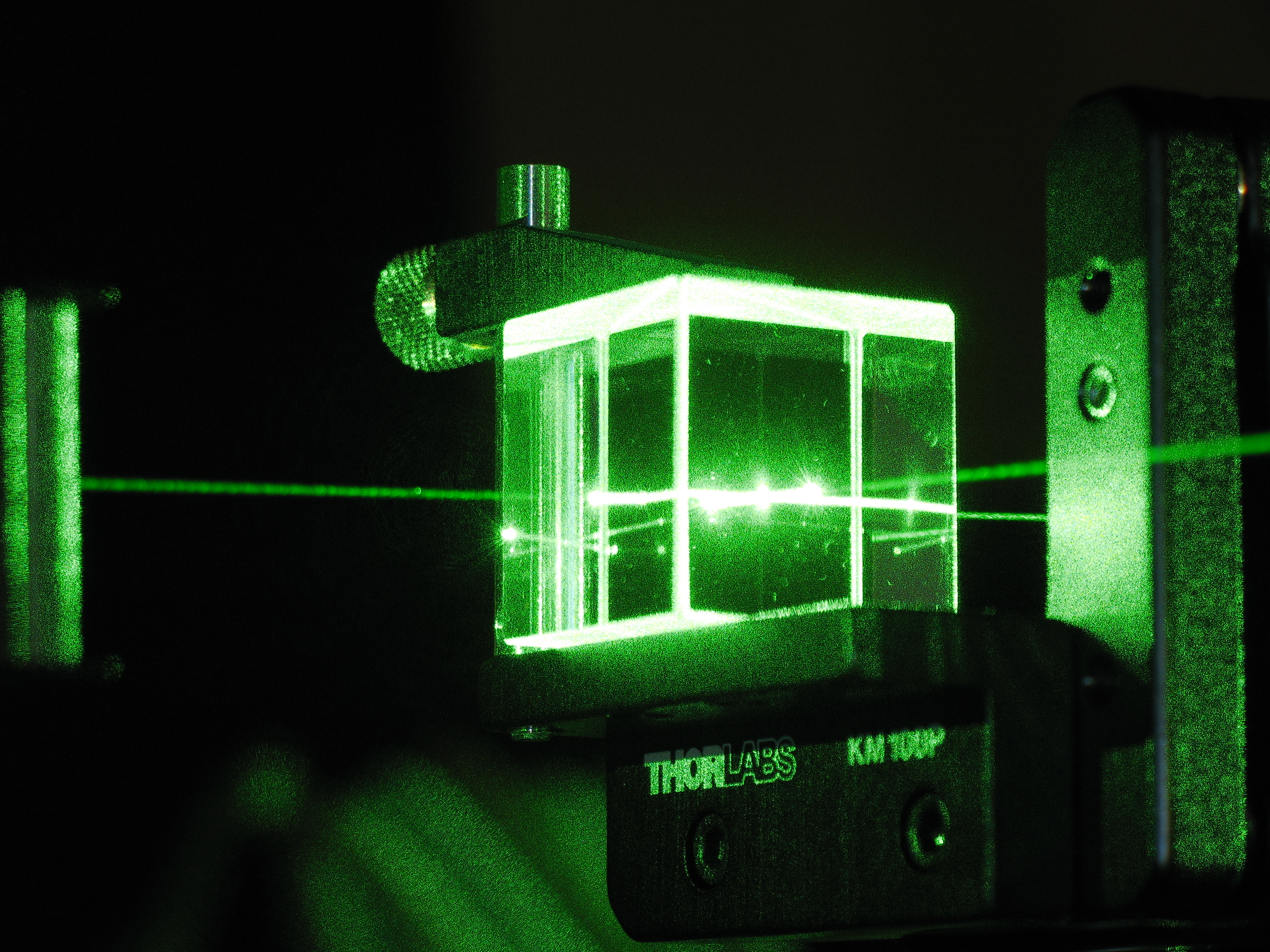

Boza, a mildly alcoholic Turkish beverage traditionally sold by street vendors

There is a Turkish cultural trait — a sweetly melancholic emotion called huzun, which Pamuk writes about at length in his memoir Istanbul — Memories and the City. As an outsider from the chipper, forward-looking US of A, my best understanding of huzun is that it’s a kind of sweet surrender to fate, a cultural shrugging of the shoulders in response to the inevitable suffering of daily life. It’s hard to imagine an outlook more antithetical to the “Go West, Young Man!” entrepreneurial spirit of the country in which my own worldview was forged, although our traditional music — blues, folk-country, Appalachian high harmony — draws from a similar well of wistfulness and sorrow at things lost.

Mevlut is kind of the embodiment of huzun. Throughout his 40 year career and the rise of Istanbul from a city of 2 million to more than 9 million people, he sells yogurt, rice with chickpeas, and boza, always making barely enough money to get by. Relatives advise him to get into some other line of work, but he cheerfully refuses, stoically shouldering his baskets each day and setting forth with a sense of inevitability and belonging. In selling boza (a constant nocturnal activity throughout his life), Mevlut is consciously calling out to and from Istanbul’s ancient past, stitching together its fragmented social fabric.* And after 200 pages of feeling frustrated with him for not being more ambitious (silly American!), I ultimately had to accept the fact that Mevlut is happy. Happy with his job, happy with his wife Rayiha and their two daughters, happy with his little life, in part because of his huzunlu acceptance that it’s his lot in life — his fate.

Meanwhile, all around Mevlut, the city is changing. One subtheme of the book (and a fact of life for Istanbul’s millions of residents) is the tectonic inevitability of massive earthquake that is expected at any moment to level the entire city. The earthquake never happens, of course, but all around Mevlut political revolutions and aggressive waves of industrialization repeatedly tear down and rebuild the city around him. Through it all, Mevlut is the constant, the only reliable thing in a world that’s constantly reinventing itself. And while contempt is an easy reaction to his intractability, his personal conservatism, he is also in a sense the soul of the city, the thing that makes Istanbul Istanbul, and that no amount of progress can erase.

*One fun note about boza: Its typical alcohol content is around 3 percent, which made it popular in Islamically strict Ottoman Turkey (prior to the establishment of the modern Republic in 1923) because people could pretend it was non-alcoholic. Even in Mevlut’s day, the few remaining boza vendors won’t admit to customers that boza contains alcohol, although everyone knows that it does. Like Istanbul (or any great city), boza is subtle, sublunary, not always what it seems.

@jgots is me on Twitter