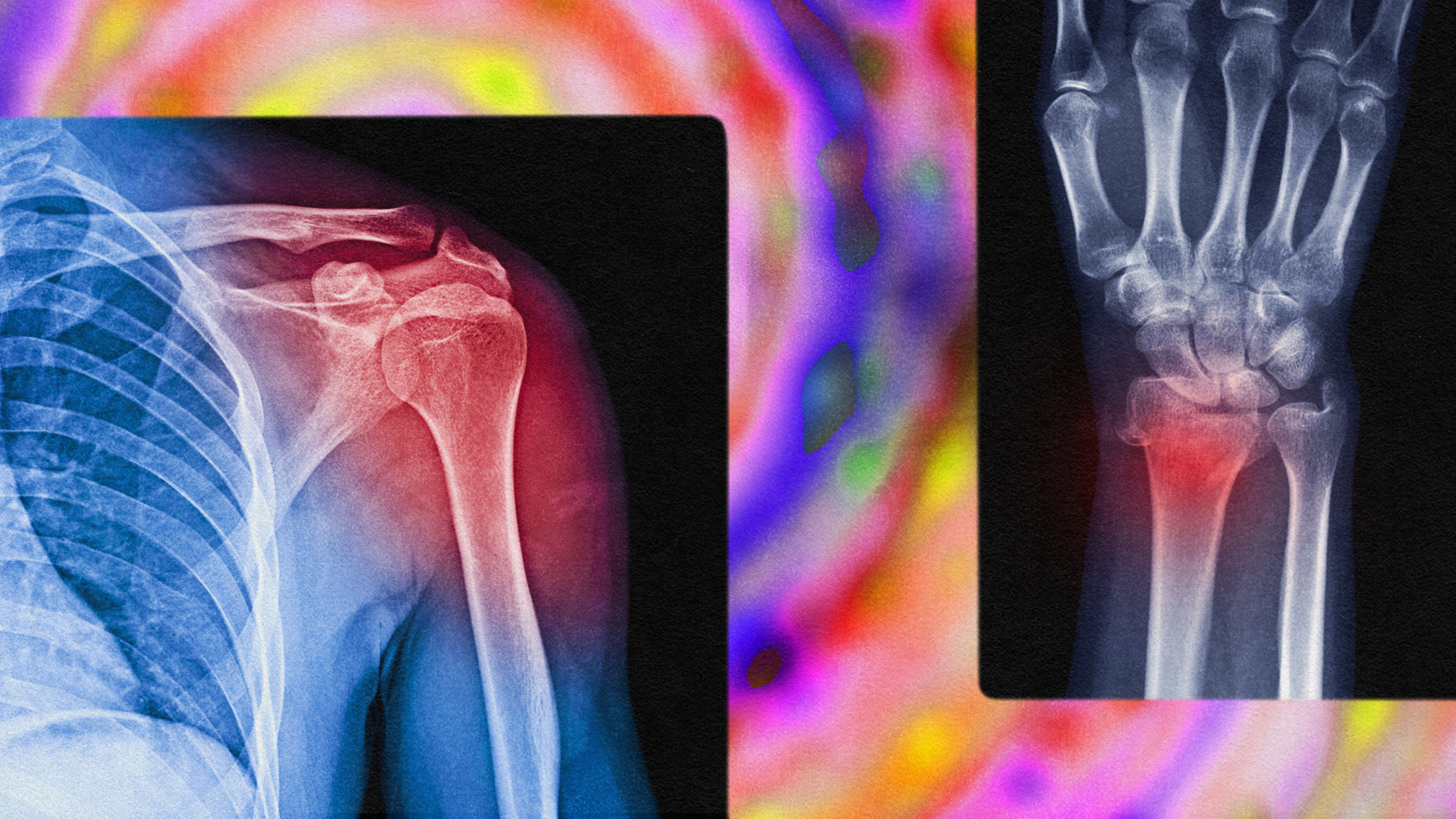

Untreated Chronic Pain Violates International Law

Untreated chronic pain is not only an epidemic, it’s a crime. According to a groundbreaking new report by Human Rights Watch, the majority of the world’s population lacks adequate access to narcotic pain relief. Governments are letting their own people suffer needlessly and flouting international law in the process.

In signing the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, the international community acknowledged that narcotic drugs are “indispensable for the relief of pain and suffering.” Signatories committed to making these drugs available to those in need. However, HRW reports that most nations are failing to live up to that commitment. Eighty percent of the world’s population currently has inadequate access to narcotic painkillers.

According to the report:

“The poor availability of pain treatment is both perplexing and inexcusable. Pain causes terrible suffering yet the medications to treat it are cheap, safe, effective and generally straightforward to administer. Furthermore, international law obliges countries to make adequate pain medications available. Over the last twenty years, the WHO and the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB), the body that monitors the implementation of the UN drug conventions, have repeatedly reminded states of their obligation. But little progress has been made in many countries.”

The report blames government inaction and excessively strict drug control policies for the global shortage of medical narcotics. Many governments are so afraid that morphine will be diverted for illicit purposes that they are willing to let sick people go without in order to keep criminals from cashing in. This warped logic is the equivalent of imprisoning the innocent to make sure that the guilty don’t go free.

The report identifies a vicious cycle of low supply and low demand: When painkillers are rare, health care providers aren’t trained to administer them, and therefore the demand stays low. If the demand is low, governments aren’t pressured to improve supply. The 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs set up a global regulatory system for medical narcotics. Each country has to submit its estimated needs to the International Narcotics Control Board, which uses this information to set quotas for legal opiate cultivation. HRW found that many countries drastically understate their national need for narcotic medicines. In 2009, Burkina Faso only asked for enough morphine to treat 8 patients, or, enough for about .o3% of those who need it. Eritrea only asked for enough to treat 12 patients, Gabon 14. Even the Russian Federation and Mexico only asked the INCB for enough morphine to supply about 15% and 38% of their respective estimated needs.

Cultural and legal barriers get in the way of good pain medicine. “Physicians are afraid of morphine… Doctors [in Kenya] are so used to patients dying in pain…they think that this is how you must die,” a Kenyan palliative care specialist told HRW investigators, “They are suspicious if you don’t die this way – [and feel] that you died prematurely.” The palliative care movement has made some inroads in the West, but pharmacological puritanism and overblown concerns about addiction are still major barriers to pain relief in wealthy countries. In the U.S., many doctors hesitate to prescribe according to their medical training and their conscience because they’re (justifiably) afraid of getting arrested for practicing medicine.

Ironically, on March 3, the same day the HRW report was released, Afghanistan announced yet another doomed attempt to eradicate opium poppies, the country’s number one export and the source of 90% of the world’s opium. The U.S. is desperate to convince Afghans to grow anything else: “We want to help the Afghan people make the move from poppies to pomegranates so Afghanistan can regain its place as an agricultural leader in South Asia,” said U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton in an address to the Afghan people last December. Pomegranates? Sorry, Madame Secretary, but the world needs morphine more than grenadine.

Photo credit: Flickr user Dano, distributed under Creative Commons. Tweaked slightly by Lindsay Beyerstein for enhanced legibility.